I cover how some people live to a grand old age — by lying about it! And why do they do that? For the money, of course! The sentinel effect, though, can prevent this from occurring. Looking at the case of the oldest man in Japan who had been dead for 30 years and more.

Episode links

Secret of Supercentenarians?

2009, NewScientist: Secrets of the centenarians: Life begins at 100

Dying of old age

"There is one, and only one, cause of death at older ages. And that is old age." So said Leonard Hayflick, one of the most influential gerontologists of all time. But dying of old age isn't just a case of peacefully losing the will to live - it is an accumulation of diseases and injuries different to those that tend to kill people at younger ages.

For a start, the oldest old have very low rates of chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease and stroke. The trend is particularly apparent for cancer. The odds of developing it increase sharply as people age, but they fall from the age of 84, and plummet from 90 onwards. Only 4 per cent of centenarians die of cancer, compared with 40 per cent of people that die in their fifties and sixties.

Many centenarians even manage to ward off chronic diseases after indulging in a lifetime of serious health risks. Many people in the New England Centenarian Study experienced a century free of cancer or heart disease despite smoking as many as 60 cigarettes a day for 50 years. The same story applies to people from Japan's longevity hotspot, Okinawa, where around half of the local supercentenarians had a history of smoking and one-third were regular alcohol drinkers. These people may well have genes that protect them from the dangers of carcinogens or the random mutations that crop up naturally when cells divide.

So what does kill off the oldest old? Pneumonia is the biggest culprit, with other respiratory infections, accidents and intestinal problems trailing behind. "Dying of old age involves total systems failure," says Craig Willcox of the Okinawa Centenarian Study in Japan. "Centenarians avoid age-associated diseases, but you see a lot of systemic wear and tear. Almost all of them have had some problems with cataracts, they can't hear very well and have osteoarthritis. Our most recently deceased centenarian in Okinawa caught a cold and died in her sleep."

2019, Vox: Study: many of the “oldest” people in the world may not be as old as we think

We’ve long been obsessed with the super-elderly. How do some people make it to 100 or even 110 years old? Why do some regions — say, Sardinia, Italy, or Okinawa, Japan —produce dozens of these “supercentenarians” while other regions produce none? Is it genetics? Diet? Environmental factors? Long walks at dawn?

A new working paper released on bioRxiv, the open access site for prepublication biology papers, appears to have cleared up the mystery once and for all: It’s none of the above.

Instead, it looks like the majority of the supercentenarians (people who’ve reached the age of 110) in the United States are engaged in — intentional or unintentional — exaggeration.

….

The paper also looks at the phenomenon in Italy and Japan, where something different seems to be happening.

Italy keeps better vital statistics than the United States does, and has had reliable vital statistics across the country for hundreds of years — yet in Italy, too, there are clusters of the country where lots of supercentenarians pop up. Maybe the Italian supercentenarians are for real?

Newman’s analysis suggests not. He starts out by noticing something fishy: The parts of Italy that claim the most supercentenarians overall have high crime rates and low life expectancy. Isn’t that weird? Why would an area generally have low life expectancy but also produce an extremely disproportionate share of the world’s oldest people?

The same pattern repeats itself in Japan: Okinawa has the greatest density of super-old people, despite having one of the lowest life expectancies in the country and generally poor health outcomes.

The paper puts forward a controversial proposal. It seems unlikely that living in high-crime, low-life-expectancy areas is the thing that makes it likeliest to reach age 110. It seems likelier, the paper concludes, that many — perhaps even most — of the people claiming to reach age 110 are engaged in fraud or at least exaggeration. The paper gives a couple of examples of how this might come about; some of it might be reporting error, and some of the supercentenarians might be produced by pension fraud (someone might be claiming a dead person is still alive for pension benefits, or claiming the identity of a parent or older sibling).

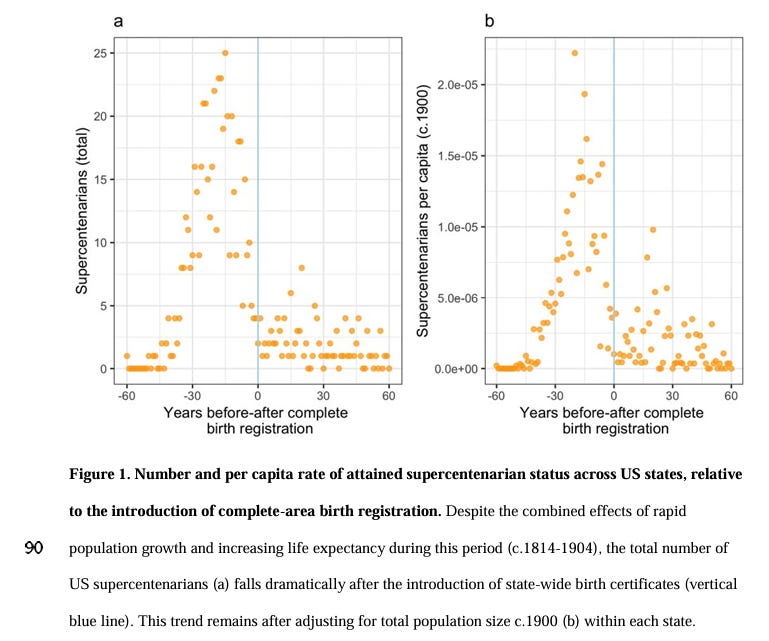

Abstract: The observation of individuals attaining remarkable ages, and their concentration into geographic sub-regions or ‘blue zones’, has generated considerable scientific interest. Proposed drivers of remarkable longevity include high vegetable intake, strong social connections, and genetic markers. Here, we reveal new predictors of remarkable longevity and ‘supercentenarian’ status. In the United States, supercentenarian status is predicted by the absence of vital registration. The state-specific introduction of birth certificates is associated with a 69-82% fall in the number of supercentenarian records. In Italy, which has more uniform vital registration, remarkable longevity is instead predicted by low per capita incomes and a short life expectancy. Finally, the designated ‘blue zones’ of Sardinia, Okinawa, and Ikaria corresponded to regions with low incomes, low literacy, high crime rate and short life expectancy relative to their national average. As such, relative poverty and short lifespan constitute unexpected predictors of centenarian and supercentenarian status, and support a primary role of fraud and error in generating remarkable human age records.

PDF: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/704080v1.full.pdf

Japan Pension Fraud

July 2010, BBC News: Tokyo's 'oldest man' had been dead for 30 years

He was thought to be the oldest man in Tokyo - but when officials went to congratulate Sogen Kato on his 111th birthday, they uncovered mummified skeletal remains lying in his bed.

Mr Kato may have been dead for 30 years according to Japanese authorities.

They grew suspicious when they went to honour Mr Kato at his address in Adachi ward, but his granddaughter told them he "doesn't want to see anybody".

Police are now investigating the family on possible fraud charges.

Wikipedia: Sogen Kato, Aftermath

After the discovery of Kato's mummified corpse, other checks into elderly centenarians across Japan produced reports of missing centenarians and faulty recordkeeping. Tokyo officials attempted to find the oldest woman in the city, 113-year-old Fusa Furuya, who was registered as living with her daughter. Furuya's daughter said she had not seen her mother for over 25 years.[12] The revelations about the disappearance of Furuya and the death of Kato prompted a nationwide investigation, which concluded that police did not know if 234,354 people older than 100 were still alive.[13] More than 77,000 of these people, officials said, would have been older than 120 years old if they were still alive. Poor record keeping was blamed for many of the cases,[13] and officials said that many may have died during World War II. One register claimed a man was still alive at age 186.[14]

Following the revelations about Kato and Furuya, analysts investigated why recordkeeping by Japanese authorities was poor. Many seniors have, it has been reported, moved away from their family homes. Statistics show that divorce is becoming increasingly common among the elderly. Dementia, which afflicts more than two million Japanese, is also a contributing factor. "Many of those gone missing are men who left their hometowns to look for work in Japan's big cities during the country's pre-1990s boom years. Many of them worked obsessively long hours and never built a social network in their new homes. Others found less economic success than they'd hoped. Ashamed of that failure, they didn't feel they could return home,"[13] a Canadian newspaper reported several months after the discovery of Kato's body.[13]

New York State Pension Fraud

July 2023:

DiNapoli: Texas Woman Charged with Stealing Over $65,000 in NYS Pension Payments

State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli announced the indictment of a 53-year-old Texas woman for allegedly stealing more than $65,000 in New York state pension payments meant for a deceased acquaintance. Christy Gibson, of Smith County, Texas, was indicted by Texas prosecutors and charged with one count of theft after an investigation by DiNapoli’s office.

“Christy Gibson went to great lengths to cover up the death of an acquaintance to line her own pockets,” DiNapoli said. “Thanks to the work of my investigators and law enforcement in Texas, she will be held accountable. We will continue to partner with law enforcement from across the country to protect the New York State Retirement System.”

William H. Walsh Jr. retired from the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in November 1986. He elected to receive a reduced monthly retirement benefit so his wife, Mary L. Walsh, would continue to receive payments if he died before her. William Walsh died in October 2005. Mary Walsh died in December 2012 and at the time of death the pension payments should have stopped. Instead, her death was never reported to the New York state retirement system.

In May 2013, the retirement system received information indicating that Walsh may have died, and pension payments were halted. In June of that year, the retirement system sought verification that Mary Walsh was still alive and subsequently received notarized verification, purportedly from Mary Walsh. As a result, the pension payments were reinstated.

A later investigation by the State Comptroller’s Office found that Mary Walsh was in fact deceased, and the verification was fraudulent.

In total, 70 pension payments were paid after date of death, amounting to $65,102.28.

The pension payments went into a joint account in the name of Mary Walsh and Gibson that was opened in 2011. Gibson never informed the bank of Walsh’s death or removed Walsh’s name from the account. It appears that Gibson was an acquaintance of Mary Walsh through her sister-in-law and also worked at the nursing home where Walsh eventually lived.

DiNapoli’s investigators determined that Gibson used the joint account to pay for entertainment and food. Gibson also made electronic transfers and cash withdrawals.

The Value of the Sentinel Effect

Product Development News, October 1998, Richard L. Bergstrom, The Underwriter’s Corner, “The Value of the Sentinel Effect (Revisited)” https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/library/newsletters/product-development-news/1998/october/pdn-1998-iss47-bergstrom.pdf