Taking the Long View: Over a Decade of STUMP Watching Public Pensions

Sticking to the Themes of Choices Have Consequences and the possibility of failure

If nothing else, I am consistent.

Choices have Consequences

13 March 2014: Public Pensions Watch: Choices Have Consequences

Remember, cutting (or not cutting) pensions is a choice.

And choices have consequences.

But more to the point, that choice lasts for only so long until the money sources go away. If the choice is to cut staffing levels or to cut services to pay for underfunded pensions, people may decide to live elsewhere.

For what it’s worth, I live in an extremely high tax location by choice. While I wouldn’t be happy with taxes going up, we are definitely getting money’s worth in services (including excellent snow clearing compared to Hartford, but that’s for another day).

If I found that services were cut to pay people for service they did decades ago….. I might not be so happy about the level of taxes we pay.

This is why public pensions need to be fully funded as close to the year of service as possible — later taxpayers may not feel all that beholden for service done in the 1970s. And it’s really difficult for retired people to strike. Especially if they moved to lower tax locales like Florida or Texas. If money is paid for the benefit when service is rendered, then pensioners are more secure.

The concept is called “generational equity” and usually talked about in terms of “fairness”. Fairness is really beside the point, because after a while, people don’t care about “fair”. They care about trade-offs, and political realities. Those who are retired and living elsewhere are in a really weak position compared to taxpayers actually in the locale and pissed off that services are being cut. And such people may not find much solidarity from fellow public union members, when those who are still working are also hit with these taxes and also have had their benefits (and hours) cut.

So choose carefully.

That was over a decade ago.

I had a December 2014 post: Multiemployer pensions, Social Security, and Public Pensions: Choices Have Consequences

There’s a lot behind the PBGC’s insolvency, part of which is that the money being charged plans to build up this fund was always insufficient.

But multiemployer plans are an especially sticky subject, because of all sorts of bad incentives baked into how these plans are regulated.

Here is one bit of info: when pensions (whether single employer or multiemployer) are put onto the PBGC because they’ve gone bankrupt, the pensions are guaranteed only up to a certain amount. Those with small pensions may get their full amount, but those with higher amounts get whacked down. A lot.

….

However, it’s not happy for highly-paid employees like airline pilots (many of whom are forced to retire earlier than age 65, btw) — that’s why they’re really not happy when their plans get put to the PBGC.

Still, MEP guarantees are especially skimpy.

You know what also has a very small amount? Social Security benefits.

“In 2014, if you retire at age 66, the maximum amount you will receive is $2,642.”

I will have more to say about MEP bailouts and the lack of Social Security reform — but that’s for next week (or later — Stu has cancer treatment coming up.)

For right now, I’m just looking at what I’ve said in the past.

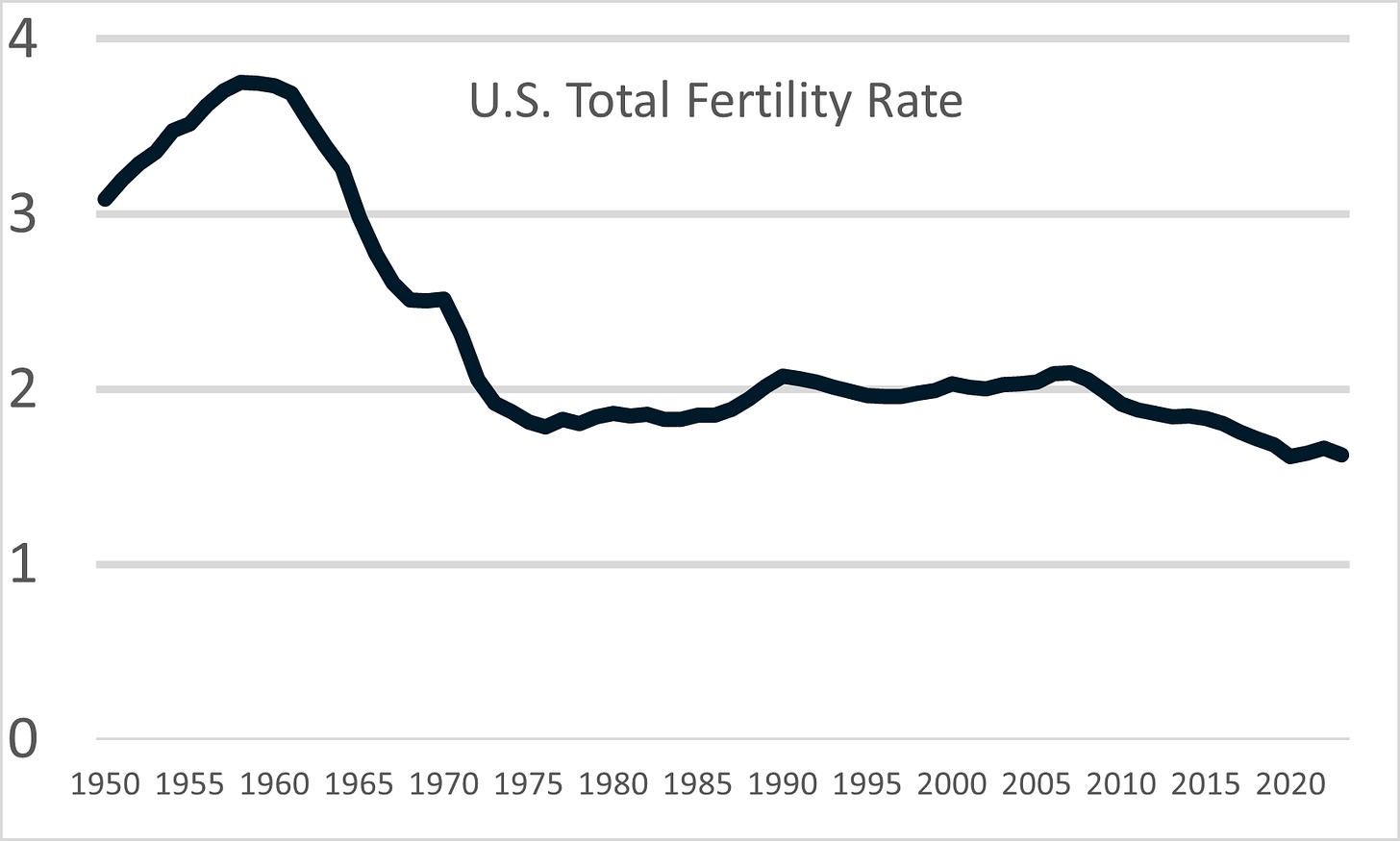

The reason the boomers are going to find out that they’re going to get a lot less than they thought is because of choices they made:

1. They didn’t save up enough and

2. They didn’t have enough childrenThat second one is a manner of saving for the future, btw.

The reason taxpayers will not boost them up is because there’s not going to be enough of us. And bringing in a bunch of low income once-illegal aliens is not going to do much for them, either, except perhaps provide some low cost workers for their assisted living centers.

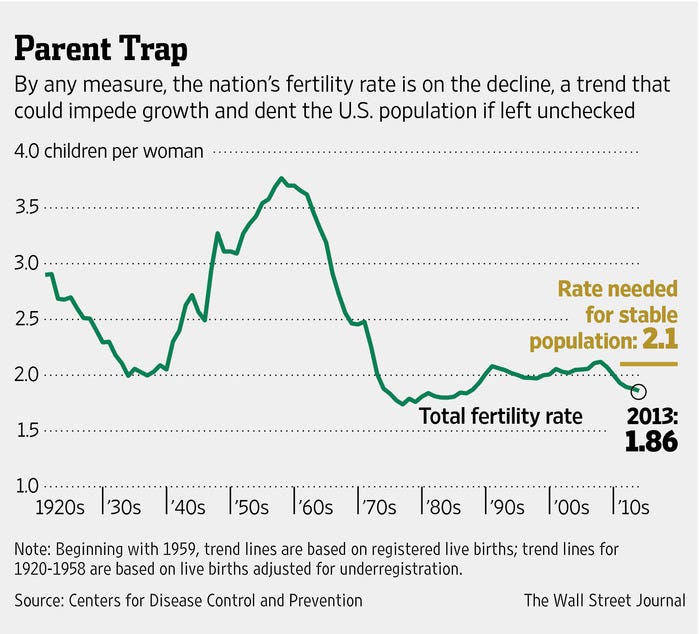

Here is an updated graph:

The U.S. Total Fertility Rate was down to 1.624 in 2023.

I was born in that lovely trough of the “baby bust” seen from 1972-1988, when the TFR dropped below 2.1 (the replacement rate). You may know us as Gen X, but we used to be called the Baby Bust for good reason.

You can also see the peak of the Baby Boom was actually the late 1950s.

From 1989 to 2008 (oh lookee there), the TFR hovered around 2.

I wonder what was going on.

But since the Great Financial Crisis, the TFR has been doing nothing but going down down down.

I will return to this Choices Have Consequences theme at the end of the post.

I Like to Watch

23 June 2014: Public Pensions: Why Keeping a Watch is Important

While some pension plans are being sunk by hideous skulduggery, for the most part it is not intentional ill-will or underhanded dealing that has caused the problem of unsustainable pensions.

Some pensions that did what they thought they were supposed to — standard benefit designs with certain minimum years of service requirement, putting in the actuarially-required amount each year, investing in a mix of stocks and bonds with good oversight — are finding the required contributions are climbing rapidly and their funded statuses are falling behind. This is not a good thing.

Of course, many public pensions did not get their required contributions. Those fell even further behind. And continuing to fall further behind.

Even when the public employee unions are not to blame for the pensions being in a poor condition, it does no help pointing at all the “bad guys”, because said bad guys aren’t going to be coughing up the money. There’s no enough money from whoever the bad-guy-of-the-day is (or said bad guys died decades previously).

Ultimately, everything comes from the taxpayers: pension contributions and current salaries both come from the taxpayers. Those “employee contributions” to the pensions are from the taxpayers.

And you can only get so much from the taxpayers.

….

Disaster is coming for many public pensions, and there are no real bailout mechanisms other than trying to soak taxpayers (and bondholders, but generally one can screw bondholders only once. So you’d better make that first screwing worth it, because it will be a long time before you get another shot at it.)

And soaking the taxpayers has some issues as well.

It is better for public employees to know exactly what is going wrong with their pensions ahead of time, so they can plan to protect themselves as best as possible (some of the Prichard, Alabama pensioners were essentially destitute when the pension fund ran out and no pension payments to current retirees were made, at all, for over a year). As well, they can collectively get together in their unions to try to figure out how they can change their pensions to something that is sustainable. Then the transition can be smoother and people will not find that there is much, much less than they need when they retire.

Too many public unions think they can brazen it out, sue money for pensions into existence, and it will all be hunky-dory. Or that they can negotiate for pay increases now while waving hands at inadequate pension contributions, thinking that the pensions will always be made whole. Somehow. Eventually.

Of course, reality doesn’t work like that. But convincing people also doesn’t work like a mathematical proof. It takes people like Craig Harris methodically going through issues, and reporting on them for years — or taking other people’s investigations/studies and promoting them, like at Pension Tsunami.

It is good to see that some public employees are taking these issues seriously and are trying to work on practical solutions before undeniable bankruptcy comes.

June 2017: Public Pensions: Why It's Important to Keep Watching

The thing is, I’ve been watching the public pension fiasco for a long time… but not as long as Jack Dean has at Pension Tsunami. And I know there are others who have remarked on this a long time ago.

Yes, this specific blog has been around only since 2014. But before that, I was at two blogs that no longer exist. But even before that, I started a thread at the Actuarial Outpost in September 2008.

Both Pension Tsunami and the Actuarial Outpost are gone. I blogged at other people’s websites for a few years as well, and those are gone.

Link rot is a problem.

It takes a long time for these problems to come to fruition.

Much longer than it takes a company to run into trouble, and much much longer than it takes an individual to fall into financial trouble.

Part of the reason is the “taxpayer put” – yes, there’s a limit to how much governments can soak taxpayers, but they can increase the taxes over time until more and more people leave and then….

Another part of the reason is the “bondholder put”, which is exercised less frequently, and does a lot more damage when it’s exercised by politicians.

The biggest part of the reason is no oversight.

Or, rather, no effective oversight.

Why I started to watch

Even though the Actuarial Outpost (the real one) is no more, I archived certain threads, and I quoted myself in posts. I quoted myself in that June 2017 post:

[the quote is from September 10, 2008, originally]

Part of posting these various articles is to dispute that “governments don’t go out of business” argument amongst other arguments. There are various degrees of things that undermine that statement – I’ve seen towns unincorporate before (though usually small), but the failure of a public pension would come far before that. There’s no such thing as infinite taxing power. Even if they could tax 100%, there would be a limit on the amount of money that would bring in. But of course, well before that mark, people would just move away. I saw the idiotic “exit tax” idea in California (I would think that’s unconstitutional but IANAL), but really towns and states can’t keep people from leaving.

I am not a pension actuary. I do not know all the details in doing pension work. I do know theory, but I understand some people disagree with theory. These theory arguments can be futile, when we’re dealing with what-ifs that some people dispute could even come into being.

I want to (for now) stick to compiling what is actually happening in real life. What are the actual consequences of the funding decisions made (whether or not actuaries are involved in that), in the valuation of the liabilities (and if certain items are treated as if they were costless)…really nitty-gritty stuff of what the current state of practice has gotten us.

For the record, California keeps coming up with its dumbass exit tax idea.

Now, by the time I was posting in September 2008, I had already been through some stuff because I had worked at TIAA-CREF (2003-2008), as it was called then. I had left TIAA by September 10, 2008.

And edited version of my telling from 2017:

At TIAA, I worked on their core product: Retirement Annuities — this is a fixed annuity product, and interest rates kept going down, down, down. This was hammering what we could credit to the annuities, and it had a huge effect on the amount in reserves and capital we had to hold to back up the annuity promises made. TIAA is a mutual insurer, so our primary goal was to maximize the retirement income we gave back to the annuity holders.

….

Here is the thing — while I had some internal constraints on how I worked my project, the really overpowering constraints came from external parties: regulators and rating agencies.

Yes, regulators and rating agencies can fail, too (and I started an Actuarial Outpost thread about that).

But here’s the thing: he were required to value our annuity promises using mortality tables that reflected that annuitants tend to live longer than the general population; using discount rates that were far far lower than 8%; and if we wanted to use equities to back our annuity promises, we’d have to hold 30% of their value in capital, in reflection that these were volatile assets backing not-so-volatile promises.

And then I heard about public pensions.

When I saw the huge disparities between what I was doing and public pensions, I was livid. I realized there were perverse incentives in how public pension actuarial practice was handled.

I got angry a few times, because sometimes we were being asked to compete with the DB pensions as an option. I wrote a few intemperate letters to actuarial magazines (where very few people read them). I asked pension actuaries, when I could get a hold of some, why they thought they could discount at 8%.

I got the “government doesn’t go out of business” line more than once. Which made me really angry.

Because I’m a history buff.

Governments go bust all the time.

Especially if you encourage them to do idiotic things in public finance.

CHOICES HAVE CONSEQUENCES

In any case, if you make promises that last decades, expect it to take decades for all the implications come forth.

Part of the reason to watch is so that people don’t say (though they will say) “How could we have known?” Buffett and Drucker were well-respected, as far as I can tell, back when I was a toddler, and even before I was born. They gave more than enough warning — and Buffett actually gets into some simple numerical examples to explain the risks. They said what needed to be done, they told you how it could have ended.

But it was easier to believe pretty stories of things always working out.

People will say “We could never see it coming! It came from nowhere!” But no, this is a slow moving disaster. Governments only pay notice when the money runs out. So that’s why I’ve started doing simple projections of when the money runs out.

Because it can.

Governments can go out of business.

Public pensions can get cut because the money has run out.

Failure is always a possibility. You may not opt for it, but you may not have an option after decades of making decisions that pushed the probability of failure closer and closer to 100%.

By the way, I didn’t know about pension obligation bonds back in 2008.

(I will not be writing about those in this post.)

When I heard about those, I hit the roof.

2023 Choices Have Consequences Series

Last year, I had a “Choices Have Consequences” series, putting together many of the themes I’ve built over the decade of STUMP.

This was partially inspired by the riots in France over the raising of retirement age to the hideously unbearable level of…. 64 years old. Though the French are some of the longest-lived people in the world.

The posts from April and May 2023:

Some excerpts from these pieces:

On underfunding public pensions:

Look — public employees have got to understand: there is no backstop if your pension plan fails.

The backstop is the taxpayer. The taxpayer who wants current services.

If you’re a retired public employee … you’re not exactly giving current services, now are you?

If people are talking about how it’s too expensive to make contributions to your pension fund to pay for the benefits already accrued in the past, and just to try to make it whole over a thirty-year trajectory, I think they’re telling you your benefits are too expensive to begin with.

They’re telling you they’re just wishing some magic money will come into being to pay for your benefits when you need them, in your retirement.

The expectation is that somebody else is going to pay in the future, though you earned those benefits in the past.

Do you want to bet on that person to appear?

The trade-offs coming up will be pensions versus current services, as I keep mentioning. The public employees and retirees need to know that they may be part of the trade-offs, and that if contributions aren’t made to their pension funds, it’s possible that they may ultimately get shorted on pension benefits. They don’t have any ERISA or PBGC backup.

People keep thinking that the bondholders and taxpayers are the ones who will get shafted… well, sure, they will get hit… too. All groups can be hurt. Public employees and retirees shouldn’t assume they will be able to escape the trade-offs.

There are some simple principles — basically, the more you promise, the more expensive it will be.

Also, if you do not put aside money for those promises, the more hollow those promises ring.

Finally, one last bit.

The Fragility of "Can't Fail" Thinking

May 2014: Public Pension Watch: The Fragility of "Can't Fail" Thinking

What actually threatens the actuarial soundness of public pension plans is behavior like the following:

Not making full contributions.

Investing in insane assets so that you can try to reach target yield. Or even sane assets that have high volatility to try to get high return, forgetting that there are some low volatility liabilities that need to be met.

Boosting benefits when the fund is flush, and always ratcheting benefits upward.

Calpers should be extremely familiar with that sort of behavior.

Here is the problem: all sorts of entities directly involved in public pensions have thought that the pensions can’t fail. Because of stuff like: constitutional protections of benefits (so paying pensions would take precedent over other spending needs, like paying for current services), “government doesn’t go out of business”, the supposedly infinite taxation power of the government, and so forth.

Because they thought that pensions could not fail in reality, that gave them incentives to do all sorts of things that actually made the pensions more likely to fail. Because, after all, the taxpayer could always be soaked to make up any losses from insane behavior.

I wrote this as Detroit was going through its bankruptcy, and part of the bankruptcy workout was cutting the pensions of people already retired.

Calpers and other interested parties did not want to see retirees being treated as unsecured creditors in a municipal bankruptcy. In the bankruptcies of Stockton and San Bernardino, for example, Calpers did not get its debts cut at all (as far as I know).

However, retirees did see their benefits cut in the Detroit bankruptcy workout, along with the very many Detroit creditors. They did not get cut as much as they could have. This was the first federal municipal bankruptcy where this occurred, and legal precedent was set. In future municipal bankruptcies, especially for very strained municipalities, other creditors may point to the Detroit precedent to make sure that they are not treated unfairly compared to all the other creditors… including retirees.

So the deeply-underfunded public pension funds might want to make sure they get into fundedness ASAP if the sponsor is in danger of slipping into bankruptcy.

Just a thought.

You have said a lot in this one. I concur that our choices do have consequences. What is our states response to low fertility rates? Thank you for the courage in presenting weighty matters.