Choices Have Consequences: Funding (or, rather NOT funding) Public Pensions

Some people are more stuck than others when it comes to public pension underfunding

This is not a new issue.

When public pensions in the United States started, many were on a pay-as-they-go basis.

Then the Great Depression hit.

So people learned that pre-funding pensions might be a good idea.

But fully funding those pensions, even with very optimistic assumptions, has turned out to be expensive.

So now, the argument is, what if we only partially funded those pensions? It’s totally sustainable! We promise!

The argument for sustainability

Before I rebut, let’s look at the argument.

By Louise Sheiner, posted at the Center for Retirement Research: The Sustainability of State & Local Pensions: A Public Finance Approach

The brief’s key findings are:

Many experts favor full prefunding of state and local pensions to maintain fiscal sustainability, which means big contribution hikes.

This analysis explores an alternative: stabilizing pension debt as a share of GDP.

Under current contribution rates, baseline projections show no sign of a major crisis in the next two decades even if asset returns are low.

Yet, many plans will be at risk over the long term of exhausting their assets, so action will be needed.

Plans can reach a sustainable footing by stabilizing their debt-to-GDP ratio, with much smaller contribution hikes than under full funding.

Mmmm, debt-to-GDP ratio, mmmm.

That sounds very abstract, and involving certain assumptions.

In particular, certain assumptions about the growth of the GDP compared to other parameters.

So let’s take a look:

Yet, full prefunding is not the only way to make a pension system sustainable.8 Indeed, even an unfunded pay-as-you-go program with a dedicated income stream – such as Social Security – can honor obligations without recourse to additional funding as long as the internal rate of return paid to beneficiaries does not exceed the growth rate of the wage base.9 Of course, pay-as-you-go programs can face shortfalls if demographic changes increase the growth in outlays or lower the growth of revenues. However, mature, partially funded systems, such as state and local pension plans, which have accumulated assets to provide a buffer, can remain sustainable even in the face of adverse shocks.

We all know about the vulnerabilities of fully pay-as-you-go systems.

But I call into question the level of partial fundedness that allows these systems to continue to supposedly continue to indefinitely sustain themselves, even through rough times.

I say almost always, when they pick a target other than full fundedness in a reasonable amount of time, they find an increasingly expensive contribution just to achieve that “sustainable” level of underfundedness. Which immediately erodes in a year of bad market returns. Then it gets more expensive to try to claw back yet again.

I say this from actual experience of how public plans have actually behaved and not some fairly simple formulas that obscure the sensitivities to all these assumptions of how public finance decisions actually get made.

Biggest assumption: that the ability to pay for future cash flows will grow

This brief is summarizing the results from this paper:The Sustainability of State and Local Pensions: A Public Finance Approach. Sheiner is one of the four authors listed.

Here’s the abstract:

In this paper we explore the fiscal sustainability of US state and local government pension plans. Specifically, we examine whether, under current benefit and funding policies, state and local pension plans will ever become insolvent and if so, when. We then examine the fiscal cost of stabilizing pension debt as a share of the economy and examine the cost associated with delaying such stabilization into the future. We find that, despite the projected increase in the ratio of beneficiaries to workers as a result of population aging, state and local government pension benefit payments as a share of the economy are currently near their peak and will eventually decline significantly. This previously undocumented pattern reflects the significant reforms enacted by many plans which lower benefits for new hires and cost-of-living adjustments often set beneath the expected pace of inflation. Under low or moderate asset return assumptions, we find that few plans are likely to exhaust their assets over the next few decades. Nonetheless, under these asset returns, plans are currently not sustainable as pension debt is set to rise indefinitely; plans will therefore need to take action to reach sustainability. But the required fiscal adjustments are generally moderate in size and in all cases are substantially lower than the adjustments required under the typical full prefunding benchmark. We also find generally modest returns, if any, to starting this stabilization process now versus a decade in the future. Of course, there is significant heterogeneity, with some plans requiring very large increases to stabilize their pension debt.

Yes, re: that last sentence — some pensions, like the Chicago Municipal fund need much bigger adjustment.

I do not think Chicago Municipal will stabilize, and the reason is the political decision-making surrounding Chicago is nuts. Forget about whether money is involved.

What constitutes a pension crisis?

Heck, I had multiple posts on whether public pensions were in crisis, all from August 2019. Here they are:

Part 1: My opinion

Part 2: Is pay-as-you-go sustainable?

Part 5: On Bonds and Bailouts

But who cares what I think. What do these authors think constitutes a crisis re: public pensions?

In their paper, on page 25, they write:

The message from these exercises is that, for the majority of plans, there is no imminent crisis in the sense that plans are likely to exhaust their assets within the next two decades.

If that’s how you define public finance crisis surrounding public pensions, then I absolutely agree. Only a few will run out of assets in the next twenty years.

Heck, most public employees (or, rather, retirees) will define it in an even more extreme way: public pensions are in crisis if and only if the benefits aren’t fully paid. You can run out of assets in the pension fund and still pay the benefits in a pay-as-you-go way.

However.

The people who do actual budgeting and financial reporting (two separate activities, remember) know the pain comes well before you run out of assets. Even in public finance.

Maybe it is not considered a crisis, but having all sorts of other consequences by having loads of pension liabilities that have not been funded will occur.

“Stabilizing” a totally artificial ratio won’t do you much good if the bond market isn’t happy with where you’re sitting with regards to your debt load, and your revenue levels as as state or municipality are just not cutting it.

Fully funded is the only protection for public employees and retirees

For me, I started with fighting the battle against those who argued that having pension funds only 80% funded was just fine.

Then Dean Baker entered, arguing that even 70% fundedness was peachy keen

https://twitter.com/meepbobeep/status/1649851875213164548

[Yes, I was involved in other fights as well.]

But here is the point: bondholders have always known they can get defaulted on, and taxpayers can move somewhere else or vote for other politicians.

But if you’re a public employee or retiree, you’re stuck.

To the public employees: think about what they’re telling you about your “promised” benefits

Look — public employees have got to understand: there is no backstop if your pension plan fails.

The backstop is the taxpayer. The taxpayer who wants current services.

If you’re a retired public employee … you’re not exactly giving current services, now are you?

If people are talking about how it’s too expensive to make contributions to your pension fund to pay for the benefits already accrued in the past, and just to try to make it whole over a thirty-year trajectory, I think they’re telling you your benefits are too expensive to begin with.

They’re telling you they’re just wishing some magic money will come into being to pay for your benefits when you need them, in your retirement.

The expectation is that somebody else is going to pay in the future, though you earned those benefits in the past.

Do you want to bet on that person to appear?

Conclusion: Fine, Short-change the public employees. But let them know that’s a possibility

Let me quote from the brief’s conclusion:

Shifting the focus to achieving sustainability by maintaining a stable debt-to-GDP ratio from the more typical emphasis on full prefunding merits serious consideration. In an effort to prefund, state and local governments have increased their pension contributions dramatically over the past 20 years. These increased contributions come at a significant opportunity cost. Despite the long economic expansion that preceded the brief COVID recession, provision of public goods provided by state and local governments remained depressed: real per capita spending on infrastructure stood at about 25 percent below its previous peak, and state and local government employment per capita also remained well below its previous peak. Notably, much of this relative decline in state and local government employment occurred in the K-12 and higher education sectors.

The research summarized in this brief is certainly not the last word on the topic. Indeed, other researchers have critiqued various aspects of the analysis.21 But, continuing with status quo or increasingly stringent full-funding policies also has costs. So, hopefully the basic idea presented here is a first step towards building a more sustainable framework for managing state and local pension plan liabilities.

I could say the reason they had to increase the contributions during that period was due to some nasty undervaluation of the pension liabilities, which led to bad dynamics of contribution patterns later. Thus “fully funders” had degrading funded ratios even though we were in a long bull market.

The reason the spending in the education sector had to decrease… was because it’s one of the largest spending sectors for state and local governments. If you’ve got to cut the budget, you cut where you’ve got the biggest budget.

There are trade-offs, as you see.

The trade-offs coming up will be pensions versus current services, as I keep mentioning. The public employees and retirees need to know that they may be part of the trade-offs, and that if contributions aren’t made to their pension funds, it’s possible that they may ultimately get shorted on pension benefits. They don’t have any ERISA or PBGC backup.

People keep thinking that the bondholders and taxpayers are the ones who will get shafted… well, sure, they will get hit… too. All groups can be hurt. Public employees and retirees shouldn’t assume they will be able to escape the trade-offs.

Related posts

2017: Why It’s a Good Idea to Fully Fund Public Pensions

100% funding is the target.

Actually paying promises is the target.

Not 80%.

Not 60%

Not cutting pensions by almost 2/3 when the governments wither away and there are no contributors left.

People talk about protecting taxpayers (who can disappear) and bondholders (who always know there’s a risk), but my primary concern is protecting retirees.

And those retirees of Loyalton, Detroit, Prichard, and now East San Gabriel Valley weren’t protected.

July 2020: Classic STUMP: Public Pensions Primer—Why Do We Pre-fund Pensions?

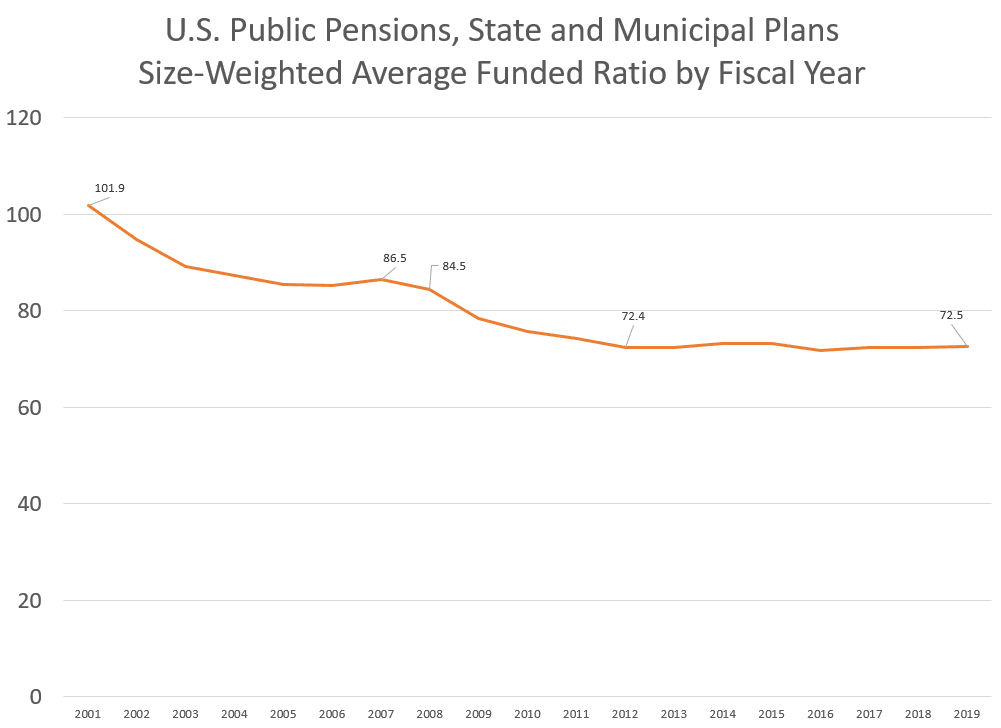

Public pensions had a decade of a bull market, and yet their funded ratios were stuck in the 70s.

Everybody knew the market wouldn’t grow forever. No, we didn’t expect this economic hit with pandemic (after all, that’s not what happened with prior pandemics), but it was expected that the bull market run would end. We were “due” a recession.

And yet, so many public pension systems merely nibbled at the edges of their problems, and seemed content to merely tread water. After all, the promises don’t all come due at the same time! We can make up for the losses over 30 years….

…..until all of a sudden, you realize the holes are too big. You don’t have 30 years to try to fill it as the fund goes into an asset death spiral, and then it’s a really unaffordable pay-as-you go situation.

It would have been best if they had fully-funded their pensions were times were good, and to build their systems so that they could better absorb financial catastrophe when it inevitably came. But most didn’t.

And here we are. Some learn lessons only in the hardest of ways, and sometimes, that may be too late.

If you can’t fix it in thirty years, you’re definitely looking at too late.