The following originally ran in November 2014: Public Pensions: What’s so Bad about 80%? (and coming attractions). This is an edited version [I updated a few links and did text clean up]/

Pension Puffery Has Been Long Standing

I have gotten a few responses to my opening of the 80% Funding Hall of Shame, many making excellent points.

First, many people pointed me to this classic piece by Girard Miller at Governing in January 2012:

This is a lengthy column, so readers can click on to any one of these topics to jump to that subject:

1. “The pension mess was caused by greedy people (from the other side), not us.”

2. “There’s no crisis. The stock market will recover and then there is no problem.”

3. “The solution is to replace pensions with 401(k) plans, like the private sector.”

4. “Experts consider 80 percent to be a healthy pension funding ratio.”

5. “Only 15 percent of pension costs is paid by employers. Investment income pays the lion’s share.”

6. “My pension contract is protected by the Constitution and can’t be violated.”

7. “States are already fixing the problem with reasonable pension reforms.”

8. “The solution is collective bargaining. There is no need for drastic legislation.”

9. “This is a $3 trillion problem when you measure it using honest (risk-free) math.”

10. “We earned more than 8 percent in the last 25 years, and will do so again.”

11. “The average public pension is $23,000.”

12. The $100,000 pension club.

I might get to some of these other issues (especially the discount rate issue, and investments… and Constitutional “protection”) again, but what is of interest is #4:

The 80% Lie Sets Pensions Up for Failure When Market Downturns Occur

Half-truth #4: “Experts consider 80 percent to be a healthy funding level for a public pension fund.”

This urban legend has now invaded the popular press, so it’s about time somebody set the record straight. No panel of experts ever made such a pronouncement. No reputable and objective expert that I can find has ever been quoted as saying this. What we have here is a classic myth. People refer to one report or another to substantiate their claim that some presumed experts actually made this assertion (including a GAO report and a Pew Center report that both cite unidentified experts), but nobody actually names these alleged “sources.” Like UFOs, these “experts” are always unidentified. That’s because they don’t actually exist. They can’t exist, because the pension math and 80 years of data from capital markets history just don’t support these unsubstantiated claims.

……

Until the last recession, respectable and world-wise actuaries would tell you privately that when a pension system gets its funding ratio above 100 percent, there is a political problem. Employees, unions and politicians suddenly become grave-robbers who invariably break into the tomb to steal enhanced benefits and pension contribution holidays. So these savvy advisors historically have tolerated modest underfunding, based on their recurring past experience with the forces of evil in this business. They figured the ideal public plan would drift between 80 to 100 percent funding over a market cycle, and nobody would be hurt if the plans were a “little bit underfunded” in normal times. Obviously that didn’t work out so well in the Great Recession, which has forced us all to take a harder look at the math and this conventional wisdom.As I have explained in one of my very first Governing columns in late 2007 (when the last business cycle was peaking), a fully funded pension plan must today have market-value assets of 125 percent of current accrued actuarial liabilities near the peak of an average business cycle — in order to offset the near-certain loss of stock market values in the following recession. Historically, that is because the 14 recessions since 1926 (including the most recent) have shrunk equity values by 30 percent on average, and equity investments represent about two-thirds of the average public pension funds’ portfolio. Real-time pension funding ratios will therefore likely decline by about 20 percent in the average recession, depending on how much the bond portfolio offsets the stock losses and mounting liabilities. So there is not a major public pension plan in the United States today that can be described as “overfunded.”

By the way, we’ve had an extraordinary bull run in the market the past five years.

Any public pension plans anywhere near 125% funded? [in November 2014]

Anybody?

Bueller?

Man, is it going to be ugly when the bear wakes up again.

How the Funded Ratio Changes from Year to Year

More to the point: the funded ratio is not a mark that stays put from year-to-year.

Each year, the total pension liability accrued increases, as more employees have worked another year (and thus accrued more of a pension benefit), and there may be raises baked in as well. If the sponsor of the pension plan underfunds even the accrual, the funded ratio can erode.

Undercontribution is not the only reason the funded ratio can erode: there is also asset underperformance (not merely losses, but not making the target 8% or whatever the target return is). This comes out not as quickly as performance, due to asset smoothing techniques.

In addition, there is the matter of people living longer. If one uses a way out-of-date mortality table, one underestimates the value of the pension for people in retirement, as they’re living to older ages.

All this experience may not be recognized immediately, but ultimately it gets recognized in the cash flows going out: those are very much real. The funded ratio can look just fine until all of a sudden, experience catches up.

That’s the difference between a balance sheet and an statement of cash flows. The first is all estimates (hopefully, based on some sort of reality, but it still is an estimate of value — both on the liability and asset sides) and the second is all reality. The second ultimately dominates, though it can be difficult to interpret over short periods of time.

Exemplar of Poor Pension Funding: Kentucky

But let us step back from all this financial theory. Let’s look at some actual pension plans.

The reason I am merely dubbing this the “Hall of Shame” is because aiming for an 80% fundedness target is not actually the worst thing that can happen to a pension.

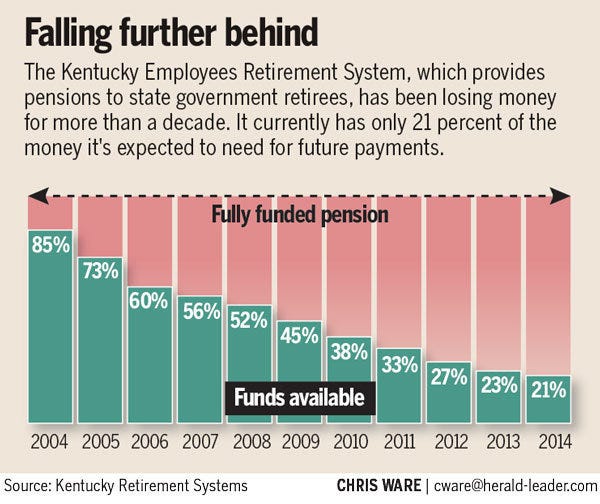

Let’s look at Kentucky’s pensions: [From Lexington Herald-Leader, November 19, 2014]

FRANKFORT — Leaders of the largest pension system for state workers learned Wednesday morning that it has only 21 percent of the money it’s expected to need for future payouts, down from 23 percent in 2013 and continuing a steady decline during the past decade.

Hours later, officials with another pension plan, the Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System, or KTRS, urged state lawmakers to consider issuing a 30-year bond of $1.9 billion or $3.3 billion to boost its sagging pension fund, which has 51 percent of the assets it’s expected to need for future payouts.

That second paragraph intimates my next target: Pension Obligation Bonds. These being OF THE DEVIL, often making bad situations worse, I am going to be opening the Pension Obligation Bonds Circle of Hell (watch for it!)

But back to that funding ratio. Let’s look at the graph:

80% funding may or may not be “just fine”, but I can tell you without hedging statements that 20% funding is hideous.

How did it get that way?

The retirement systems for county employees and state police appear to be stabilizing somewhat, based on preliminary numbers, officials said. But the $2 billion Kentucky Employees Retirement System, or KERS — which includes 118,325 people in non-hazardous jobs — has only 21 percent of the money it’s expected to need for future payouts.

This was the first fiscal year under a pension reform plan in which the legislature paid the full annual required contribution — known as the ARC — into KERS, but it likely will take several more years of full ARC payments before funding levels rise, said Bill Thielen, KRS executive director. Despite an investment return of about 15 percent, the KERS pension fund lost $182 million for the year.

“If you don’t have the assets to invest, you don’t gain as much,” Thielen said.

No shit, Sherlock. But watch out — that argument will be used to justify a Pension Obligation Bond, and given the single direction of the deteriorating pension funding ratio for a decade, through both good and bad markets, I would think bond investors might be a bit skeptical of Kentucky’s fiscal discipline.

What Happens to Bondholders in Municipal Bankruptcies?

Recent municipal bankruptcies of Stockton and San Bernadino in California have shown that bondholders will be the first to get screwed in the event of governmental insolvencies, esp. driven by the cost of public services (and benefits for said employees). In both Stockton and San Bernadino, though given the go-ahead to possibly cut pensions to try to dig out, the politicians involved in the bankruptcy workouts decided to not cut (unlike with Detroit).

Think about how bad it will be when a state, which cannot use the federal bankruptcy process, goes de facto bankrupt. The bondholders will definitely get it in the shorts. (Can one short bonds? I’m sure somebody has something worked out…)

Keeping Track of Causes of Underfunded Public Pensions

Back to the undercontribution issue — as noted in my recent post on telling the actuaries what you need to know, there have been comments on public pension funding practice, and actuarial practice surrounding that.

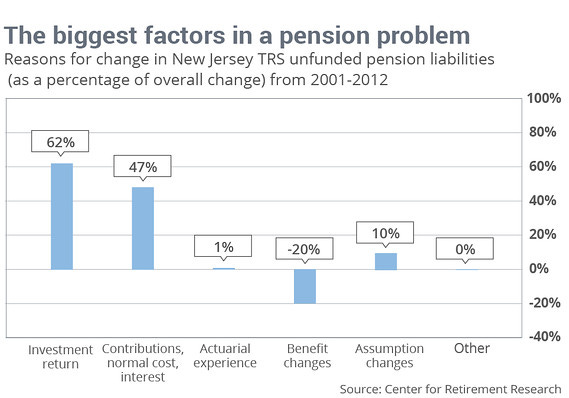

My own letter asked for a long-term historical look at the causes of changes in the unfunded liability. What I had in mind was something akin to what Alicia Munnell writes about here:

While we can’t solve all problems, my colleagues and I would like to toss a proposal for a new analytic tool into the mix. It is not so much prescriptive, but rather will make clear to the plan sponsor the extent to which the plan is making any funding progress. This tool would highlight, on a historical basis, the specific reasons why the unfunded liability has been growing. Every plan’s actuarial valuation reports the Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liability (UAAL), the change in the UAAL from the prior year, and some information on the factors that led to the change. The task is to simply combine these annual changes over an extended time period.

You can look at an example table here at the link, but I think people like graphs.

I am working on a graph that may be a little more involved, but that’s for later.

One can see that in this specific example, the causes for the growth in the unfunded liability are primarily investment underperformance and undercontribution to the plan. I have looked at similar tables and graphs for multiple pension plans, and those being the primary two drivers of the unfunded pension liability is fairly common.

Why One Should Track Causes of Underfundedness

There are two reasons both I and Munnell propose this tool (I have not spoken with Munnell, so I assume we independently came up with this… but for the same reasons):

1. This information is already available in annual form in official financial documents for the plans. So it would just take someone going through several years’ worth of documents to compile the info.

The actuaries working on the plans should already have a historical record, so it would involve little extra work for them. But also outsiders can put these together.

2. The development of trouble in pension plans usually takes several years to come to fruition, partly due to all the smoothing techniques. But reality always wins. One can see that reality unfold over time, and you can start to see stuff like:

a. the plan needs to reduce its return assumption and

b. contributions need to be increased.

It’s pretty simple. Kind of like a dieter using a tracking app, and noticing they aren’t losing any weight. Then they check their daily stats and discover: they need to actually eat less, and increase their activity.

Keeping Track of Creeping Disaster

Acknowledging reality is not fun for either dieters or pension plan sponsors, but if one wants to avoid disaster, it is best to figure out the problem ahead of time before complete disaster.

Which is one reason why Pension Obligation Bonds are so dangerous. They put off the day of reckoning by making the balance sheet of the pension plan (but not the sponsor) look better.

But more on that in a later post.

Postscript: Lookback from 2020

I will revisit Pension Obligation Bonds in a future STUMP Classics, but I want to point out some very obvious takeaways from the above.

In November 2014, we had had great market growth for 5 years, and as of January 2020, the market was sitting even higher. Sure, we had had a few “sideways” periods in the equity markets, but no true “correction” in the traditional sense for a long time. The cumulative growth, theoretically, should have put public pensions back at 100% fundedness as seen right before the dot-com bust.

And it didn’t.

As I wrote in Public Pensions Before the Storm, a great number of U.S. public pension funds were sitting around 70% fundedness… not even 80% funded!

Then we have the “bad actors”, who have been that way for a long time: Illinois, New Jersey, and Kentucky topping that group.

What will they look like now?