Public Pension Concept: Plan Long-Term for Long-Term Promises, and Don't Give Contribution Holidays

A Lesson from Washington State

For those who added on because I cover mortality trends, I also cover public pensions and other public finance issues. If you only want to read the mortality issues, you can read just the posts in Mortality with Meep.

Today’s post is on the supposedly “overfunded” pensions of Washington State, and some changes some people are asking for right now.

News Hook: “Overfunded” Pensions in Washington State

30 Jan 2023: Washington’s overfunded public pension system could cost taxpayers, officials say

While other state public pension systems face large unfunded liabilities, Washington's faces the opposite problem: potential overfunding due to strong long-term returns on investment and a combination of state and public employee contributions.

However, the situation could still lead to budgeting problems for various reasons. The underlying one is that funding levels for pension plans are estimated based on numerous assumptions about long-term economic prosperity, beneficiaries' life expectancy, inflation, and interest rates.

Adjustments to some of those assumptions, as some lawmakers have proposed this session, can easily alter a plan's solvency.

In Washington's case, if the funding levels go above and then below 100%, it can create abrupt spending mandates in the state operating budget. Additionally, the state has continued to look at adding additional benefits for two pensions still in the red, which would add an additional burden to local government budgets.

Currently, Washington taxpayers spend almost $200 million per biennium on the public pension system through the state operating budget to cover the only two pension plans remaining with unfunded liabilities. One is expected to be fully funded by 2026, while the other is expected to be fully funded by the end of this year.

However, the Office of the State Actuary warns in a recent report to the legislature that this could create issues in the future. Among them is that public employees would still be required to contribute to those plans at the same rates even though they have surplus funds.

There is nothing unique to Washington State having contributions and performance dependent on a number of assumptions.

All public pension systems, more or less, operate this way.

This is the stupid part (I’m jumping ahead):

Washington's system isn't designed well to go from fully funded back to an unfunded liability, according to an October 2022 Pew Trusts analysis of state public pensions, which observed that "contribution rates fluctuate in parallel with financial market ups and downs." State law sets minimum contribution rates from the legislature into the two unfunded pension plans. If fully funded or overfunded, the state is not required to make any contributions.

But, if the pension investments failed to meet expectations or the estimated funding levels decreased, the OSA report warns it would create "another large change in rates from zero back up to the minimum rate. This would lead to rate and budget volatility."

They’re not required to make contributions, but they should make contributions, as one year of good returns will not necessarily stay up there.

This is how many systems got into trouble in the first place.

They don’t make contributions when not required, when times are good, even though that’s when they have the greatest ability to make contributions.

And then, when times are tough, they’re “required” to make contributions… and they’re really unable to. So the pension funds start dropping behind.

I’ll come back to the article in a bit. Let’s look at how well the Washington state funds are doing.

Washington State Pension Funds

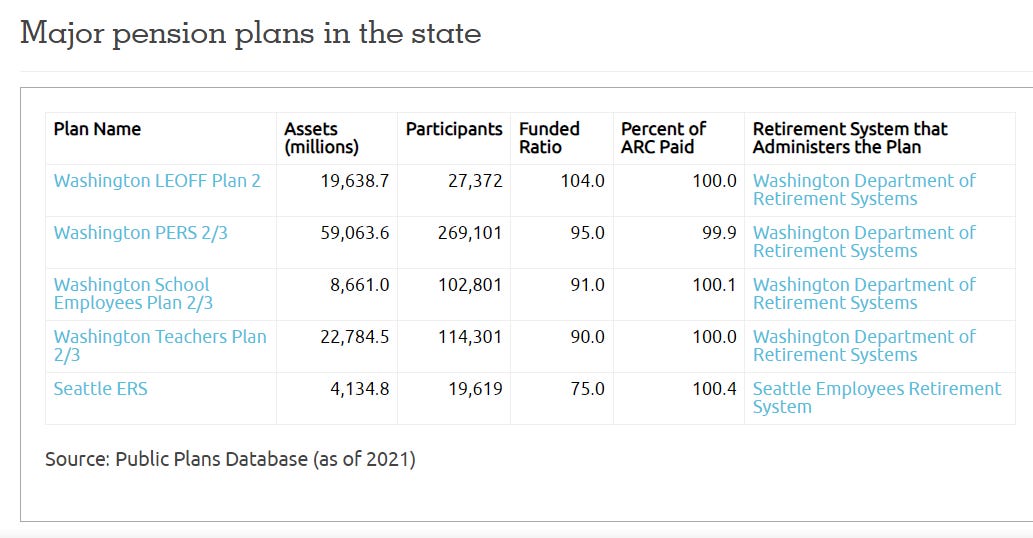

At the Public Pensions Funds Database, let’s check the Washington State funds:

You will see five funds listed, with the first four being state funds, and the fifth being a Seattle fund.

Of the four state funds, to keep things simple, let’s pick Washington PERS 2/3, as it has the most assets, the most participants, etc. As of the date they measured these funds, they have a funded ratio of 95%, which is for fiscal year 2021 (probably July 1, 2021).

Let’s check their assets:

You may see that and think — wow, that looks great! I see that huge step up in 2021 and I think that looks questionable in terms of long-term results.

If FY ended June 30, 2021, well, yeah, July 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021, is going to show great results, just for the regular equity markets. I happen to know what the equity markets have done since then.

So if we look at this fund’s performance:

FY2021 had historically super-high returns.

FY2022 isn’t going to have anything as bad as FY2009, but it still was a down year.

About those assets…

Let’s take a look at how the Washington state fund assets are allocated:

On the right is the general allocation for similar state and local pension funds. About half are broad-based publicly-traded equities, and another quarter are bonds. So about 75% are what I would call “traditional” core assets.

On the left, we see what Washington state has been doing.

About half of their assets are what I would call “traditional”.

Over 25% is private equity. Over 16% real estate. It’s not labeled, but commodities are at 5.5% of the portfolio.

This will be relevant in a moment.

The lag in measurement for public finance

Note that the above numbers we’re looking at relate to measurements taken on July 1 (or June 30) 2021.

As noted above, the S&P 500 now (Feb 2023) is below where it was in July 2021.

For bonds, we’ve got the issue of interest rates having increased — which is great if you bought new bonds at higher rates, but for your older bonds, their market value drops as interest rate levels rise, and thus their total return also drops.

That’s not including stuff like assets such as FTX which have completely cratered — I had gotten an email from Truth in Accounting where they noted they saw many municipalities looked better than they had expected in one of their annual ranking lists they make. But then they realized a bunch of pensions had gotten last measured in mid-2021 for the most recent report they were making.

Now, this is not the deciding item, but one thing they noted that one investment, in particular, had led to spectacular investment returns in mid-2021: FTX.

No, none of these are Washington state. That’s not my point. My point is that public pension fund management is a long-term project, and that a single snapshot, whether showing a fabulous return for a single period, or a horrid one, is not going to tell you much.

It’s the results over the long run.

Over-reacting, one way or another, to the most recent piece of news for a pension fund is going to get you into trouble, one way or another.

Getting too exuberant over a good return, especially over a year after that return actually occurred, for instance, may erode solvency in a fund when it’s being eaten away by bad returns that inevitably occur.

Back to the news piece

Because it’s not just the “over-funded pension fund is bad news” that’s the hook.

It’s that there is high inflation now, and Washington state retirees, like many other public system retirees, are going to want to see inflation-adjusted retirement benefits.

Already there's been efforts to add a cost of living adjustment (COLA) to certain pension plans. SB 5676, enacted by the Washington state Legislature in 2022, adds a one-time COLA to the beneficiaries of two state pension plans. It's estimated to cost $161 million through the 2025-27 biennium – though the cost is borne by cities and counties for their employees.

It was the third time the state has done that; the other increases for those plans occurring in 2018 and 2020. In a 2021 Reason Foundation blog post, Frost estimates that the 10-year costs of those COLAS were $305 million and $381 million, respectively.

"These costs necessitated increased contributions for state and local government employers," he wrote.

Frost told The Center Square that the overfunded system means "the state and local governments are going to pay more than they needed…employee groups are going to take advantage of that."

Stokesbary has also introduced HB 1057 at the behest of the Select Committee on Pension Policy, which would provide yet another one-time COLA for those two plans, costing $173 million through the 2027-29 biennium, while tasking the committee to study and recommend an ongoing COLA moving forward. The bill received a Jan. 26 public hearing in the House Appropriations Committee.

The way these COLAs compound has a way of eating at pension fund solvency very rapidly.

Yes, the hearings will likely point to the high funded ratios of the plans, in addition to current inflation, but the issue is the current funded ratio is based on great investment results from a couple of years ago, whereas the past 2 years have been very rocky. So the “actual” funded ratio right now is very different from that of 2021.

In addition, the COLAs have ongoing effects, as opposed to one-time effects that these changes are usually argued to have. This happened with “13th checks” and Detroit pensions. They were pretended to be ad hoc adjustments, but they became permanent features of the pensions (until, very rapidly, they were no longer permanent when the city went through bankruptcy.)

Let’s see how overfunded these plans actually are

But now I am going to step back for a moment.

How overfunded are these public plans, actually?

We know the assets will likely not be at such elevated levels, given recent market roller-coaster rides. That’s the numerator portion of the funded ratio — Assets/liabilities.

But what about the liability measurement?

Actuarial Standard of Practice 4 has had an update. And wait, what’s this? It goes into effect on February 15, 2023.

When performing a funding valuation, the actuary should calculate and disclose a low-default-risk obligation measure of the benefits earned (or costs accrued if appropriate under the actuarial cost method used for this purpose) as of the measurement date.

….

The actuary should provide commentary to help the intended user understand the significance of the low-default-risk obligation measure with respect to the funded status of the plan, plan contributions, and the security of participant benefits. The actuary should use professional judgment to determine the appropriate commentary for the intended user.

A low-default-risk obligation risk measure of benefits earned in Washington state (or any other state) wouldn’t be valued at 7% interest rates in our current environment.

To be sure, official reports will still be based on GASB, etc., but ASOPs are part of what is required of actuaries practicing in the U.S.

So I really look forward to reading actuarial valuation reports on all sorts of pension obligations (as this is not specific to public pensions) under this new ASOP.

Unrelated special request - could you run an analysis on Years of Life Lost comparing the excess accidental deaths to Covid deaths for 2020 and 2021? Back of the envelope I come out with YLL greater in the accidental deaths despite being 1/10th the number due to age difference.

Could you do it properly? Will gift a subscription :)