Calpers Follow-up: Hedge Fund Exit and Private Equity Rise -- and a Look at an Ohio Lawsuit

Is anything changing?

Last week, in a post on the exit of the Calpers CIO, I highlighted the odd private equity allocation trajectory of Calpers:

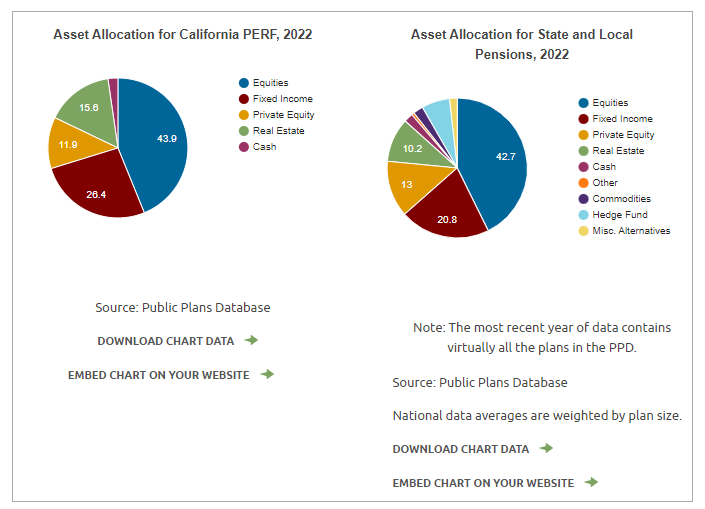

This was the latest pie charts comparing Calpers’ allocations to similar pension plans’ allocations:

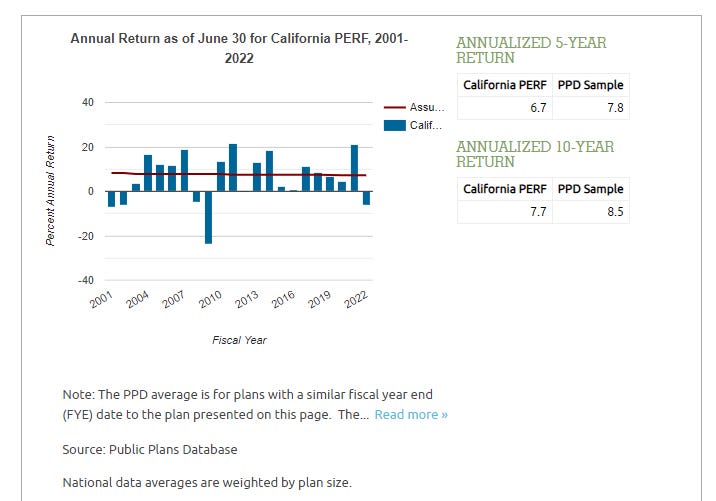

There was also this resulting performance over the years:

In this follow-up, I’m going to look at other aspects of this allocation and performance, but first, I’m going to take a detour to a public pension fund lawsuit with respect to private equity investments.

A lawsuit over private equity investments in Ohio

Yesterday, I saw this post from Edward Siedle:

Let me pull out the bits I want to discuss:

A decision is expected soon regarding a lawsuit filed over two years ago on behalf of tens of thousands of members of the Ohio Retired Teachers Association demanding that the $100 billion State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio disclose information about its private equity holdings—information which the SEC considers vital to protecting workers’ retirement savings. In complete disregard for regulatory concerns, STRS Ohio and its Wall Street money managers have long been committed to maintaining secrecy regarding tens of billions of state pension assets invested in over a hundred of these costly, high-risk private funds.

….

The SEC warns that because of their long-term investment horizon, an investment in a private equity fund is often illiquid and it may be necessary to hold the investment for several years before any return is realized. Private equity funds typically impose limitations on investors’ ability to withdraw their investment—often 10 or more years.

….

When investing in a private equity fund, the SEC notes that an investor usually receives offering documents detailing material information about the investment and enters into various agreements as a limited partner of the fund. These offering documents and agreements should disclose and govern the terms of the investor’s investment throughout the fund’s life, including the fees and expenses to be incurred by funds and their investors. These materials, which the SEC advises all investors (including participants in public pensions) read carefully, are the very same documents which members of the Ohio Retired Teachers Association have long demanded to see and STRS Ohio and its Wall Street money managers have steadfastly refused to disclose.

….

Last year, it was reported that the $440 billion CalPERS state pension sold a record $6 billion in private equity stakes to Wall Street at a 10 percent discount. That amounts to a $600 million transfer of workers’ wealth to Wall Street, in my opinion. Discounts on private equity secondary sales can be far greater, as much as 50 percent. In short, private equity assets may be grossly inflated, thus making public pensions appear better funded, i.e., less underfunded, than they really are. For their protection, pension stakeholders need access to information regarding private equity portfolios and corresponding values—they very information STRS Ohio and Wall Street are fighting to keep secret.

So, I will get into a few things here.

The main reason the private equity managers and funds don’t want this stuff public is because it’s PRIVATE equity.

If they wanted to go into public asset management, with all the SEC disclosures and requirements that entails (with the dangers of those sorts of lawsuits), they would have structured their fees (and priced them) accordingly. They do not want to set a precedent.

It doesn’t require anything nefarious to understand that.

That said, these are institutional funds involving private pensions. I have argued before that while illiquid assets are fine for public pension funds, at least for a portion of the portfolio, opaque assets may not be fine. There may not be appropriate oversight, and that’s what Siedle is arguing here. I agree.

Looking at alternative assets in public pension funds

In my last of the “Choices have consequences” series, about public pension funds chasing investment returns via alternative asset classes, I had noted writing by Siedle before on this lawsuit as well as a piece by David Sirota on these types of investments:

That said, it doesn’t really what the original motives were, when pension fund governance is lacking.

For all I might disagree with Edward Siedle and David Sirota about the motives behind the large shift into alternative assets by public pension funds, I do agree with the issues about lack of transparency and inadequate governance by public pension trustees.

….

Public pension funds are chasing returns, but those who are supposed to be providing oversight have a questionable level of ability to provide adequate oversight.

And unlike with public securities, which has plenty of publicly-reported values for taxpayers, retirees, public employee unions, and other interested parties to check, these private assets have no values one can really check until they are actually turned into cash.

It’s a matter of “trust us”… and there has been plenty of reasons not to trust based simply on assertion, don’t you think?

This is what allocations to alternatives have done the past two decades, using data from the Public Plans database:

Using that median of about 30% in 2020 - well, in 2020, Calpers was 0.9% cash, 28.2% fixed income, and 53.1% in public equities = 82.2% in core traditional assets, 17.8% in alternatives — kind of low compared to other public pensions.

Ohio Teachers has an allocation trajectory that looks like this:

In 2020, their allocation was 2.6% cash, 19.4% fixed income, and 48.1% equities, at 70.1% core traditional assets, with 29.9% alternatives. They’re smack dab at the median for U.S. public pension funds, generally tracking with the group.

What was their performance?

Now, one may say, as the Ohio plan is doing fairly well compared to their peen pension plans, what, exactly is their complaint?

However, this is just a snapshot of the performance. This does not mean it will persist. Also, this includes some measurements of illquid assets… and they’re not all cashed out yet. Don’t be counting those chickens yet.

Illiquidity for yield cuts multiple ways

As noted by Siedle above, Calpers exited some private equity holdings at a “haircut” of 10% as reported in a Bloomberg story in July 2022.

In my prior post, I had dug up three posts from 2014:

Public Pensions Watch: California pension fund pulling out of hedge funds

Public Pensions Watch: Reactions to Calpers Pulling Out of Hedge Funds

Public Pensions Watch: More Reactions to Calpers Pulling Out of Hedge Funds

The first links to a Wall Street Journal story, dated September 15, 2014:

Calpers to Exit Hedge Funds (2014)

The largest U.S. public pension plan is getting out of hedge funds as part of an effort to simplify its assets and reduce costs, a retreat that could prompt other cities and states to consider similar moves.

The California Public Employees' Retirement System said Monday it would shed its entire $4 billion investment in hedge funds over the next year.

Given how fiscal reporting is, that should mean the hedge funds allocations would go to 0 by FY2016 (as fiscal years tend to end June 30, and this was September 15.)

This is how it actually went: [data from the Public Plans Database]

Well, that was one really long year.

To be sure, they may have changed their mind about exiting. Some stuff had been going down:

Well, actually, the ex-CEO of Calpers pled guilty this past summer of all sorts of investment shenanigans:

The ex-CEO of CalPERS, Fred Buenrostro, has just pleaded guilty to accepting doucers, cash bribes and fees for placing investment business with a specific firm.

But it’s not only that hedge funds are opaque — it’s that they also have barriers to the investors getting their money out. They commit to having their money tied up for certain periods of time. I keep harping on illiquidity, which has its uses (going back to the TIAA-CREF theme – for one of its core products, a retirement annuity account, the fastest you can get all of your money out from it is over a 9 year period. There are good reasons for this.)

But the question becomes how good of an idea is having a bunch of one’s portfolio being illiquid if the pensions they’re covering are underfunded?

If you told the me of 2014 it took until 2022 to exit the hedge funds, I would not have been surprised.

Same as it ever was

At the time I was writing in 2014, the most recent funded ratio I knew was 70%.

What is the funded ratio now? [most recently available]

Basically, same place.

So this is what Calpers is trying to hire a CIO into. I wish them well, but this does not seem to be changing much.