Updated Public Pension Projection Tool -- Includes Fiscal Year 2022 Data

Merry 4th Day of Christmas!

While others may be sending calling birds on this, the 4th day of Christmas, I’ve got an updated spreadsheet to do simple cash flow projections of major U.S. public pensions, with an asset balance.

Spreadsheet: with FY 2022 Data

Basic info: Public plan data comes from the Public Plans Database.

The Public Plans Database (PPD) currently contains plan-level data from 2001 through 2022 for 229 pension plans: 121 administered at a state level and 108 administered locally. This sample covers 95 percent of public pension membership and assets nationwide. The sample of plans is a carry-over from the Public Fund Survey (PFS), which was constructed with an eye toward the largest state-administered plans in each state, but also includes some large local plans such as New York City ERS and Chicago Teachers.

Some of the plans didn’t have FY2022 data in there, but that was okay. As long as I had data that looked “okay” up to the last year available, I kept it. I still had to remove a handful of plans.

The model used for projections is extremely simple: a constant investment return, and constant growth rate for various cash flows:

Contributions

Benefits

Expenses

I project only to FY2040, as even a decade’s worth of projections with such simplistic dynamics is questionable.

Example Plan: Chicago Teachers

Let me play around with one pension plan to show you how to use the tool.

The main interface tab is “Projection Results” - the other tabs have the data, lookups, and calculations.

First, select the plan you want from the drop-down list:

I usually keep my version of Excel on manual calculation, so you may need to hit F9 (aka, tell Excel to calculate the spreadsheet).

Plan Statistics

In the upper right hand corner of the Projection Results tab are the Plan Statistics:

The stats are given on 5-year and 10-year lookbacks from the last available data year. The growth rates are compound annual growth rates. The investment return is the geometric average over the period.

Those are actuals, and I included the worst historical return as I once had a stress test in this projection, to drop the asset values in 2020 (a pandemic economic stress test). But that was starting to take the model into a complicating issue that I didn’t want to give out as a general tool.

These 5-year and 10-year stats might give one an idea of what may be useful inputs for the next step.

Projection assumptions

Underneath the plan selection are the projection assumptions - and you can see these match up with the 5-year and 10-year averages.

I usually start with an all-zero assumption set as a model test. This means the cash flows in and out remain constant (until the assets run out) — so annual contributions remain constant, benefit cash flows out remain constant, and expenses remain constant.

A 0% investment return means there in no investment income (or losses) — so the asset values go up and down solely due to the cash flows.

Cash flow graph: lower right

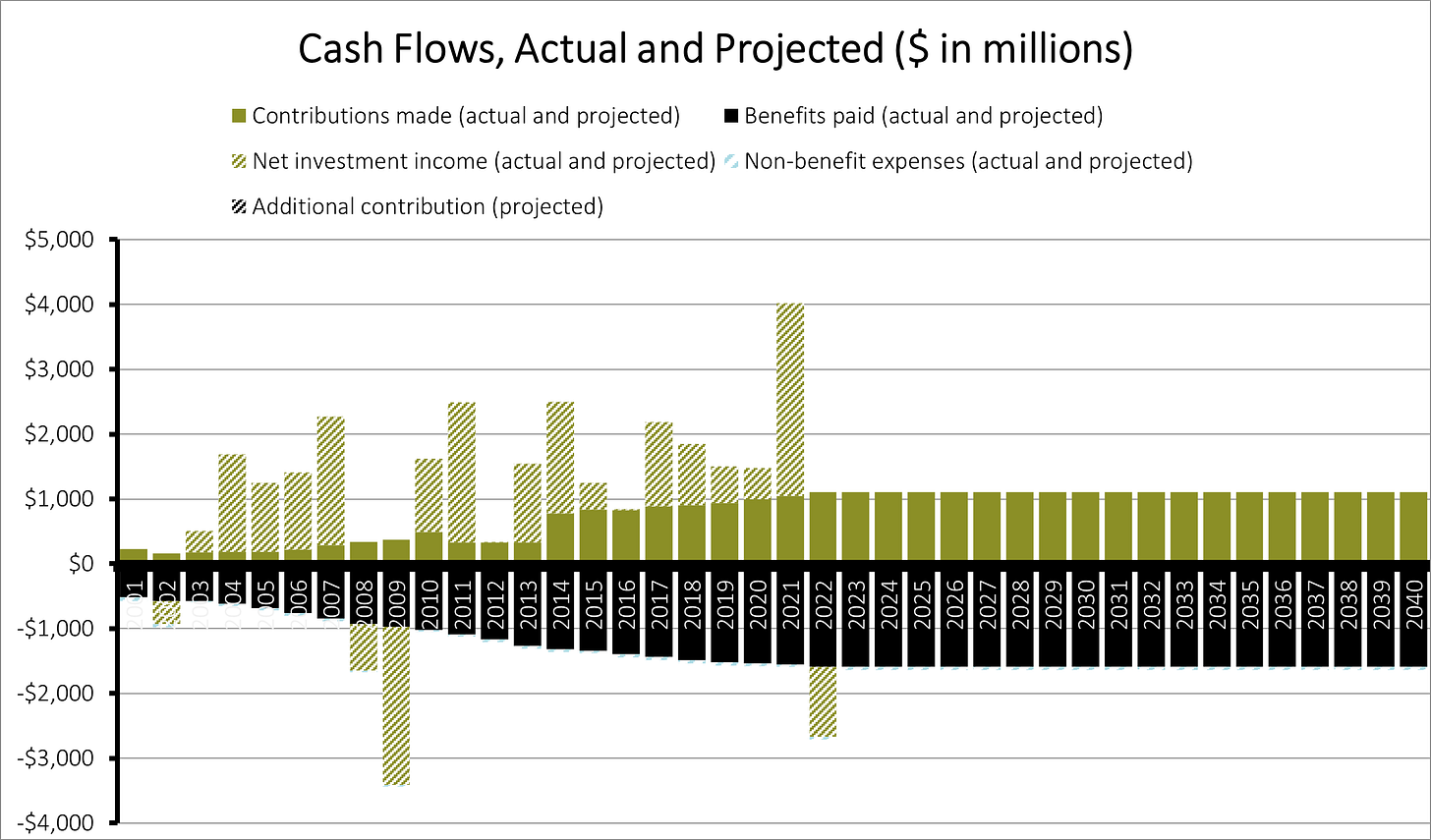

Here is the result of holding all the input assumptions at 0. Cash flow graph is in the lower right of the spreadsheet:

In this graph, there is no distinction made between actual and projected for most of the elements.

For 0% investment return in projection, there is no net investment income projected (those are the shaded green bars that can be either positive or negative).

You can see the solid green bars, the contributions, are held constant past 2022. These are always positive.

The black bars, which are the pension benefits, are always negative. For this assumption set, we assume they do not grow past 2022.

For this and most pension plans, you’re not going to be able to see the non-benefit expenses, because their magnitude is so much smaller than everything else. But I included those cash flows as they do exist.

Asset graph: lower left

Finally, the resulting asset values for the plan are in the lower left graph.

For this particular plan, unsurprisingly, as the benefits are higher than the contributions, the asset amounts simply decrease.

That said, the benefits, contributions, etc. not changing is not a realistic set of assumptions.

To be sure, this entire model is simplistic, but it’s good to “explore the parameter space” to see the behavior.

Matching 5-year average stats

Let’s try the situation of matching the 5-year stats for Chicago Teachers.

Assumption set:

Cash flows:

Assets:

Hey! That looks great!

Funny how we don’t see any pensions with such behavior with their assets.

Because… let’s be real. The pension benefits would not remain restrained in amount if the assets were growing like this. This would be seen as an opportunity to provide a benefit boost.

Stress test: Increasing benefits, not contributions or investments

Let me give you an example of the assets running out:

Here, the benefits increase 2.5% each year (compounding), the investments aren’t doing anything, and contributions aren’t increasing.

Let me show the asset results first:

In the spreadsheet, if the assets run out before 2040, it will note that:

Note the second number - after the assets run out, the plan is pay-as-it-goes status, so contributions have to increase to match the benefits.

Future Testing

I needed to update this tool for my purposes to test out specific plans.

The list of older posts below will give you an idea of what uses I may be putting this to:

April 2017: Watching the Money Run Out: A Simulation with a Chicago Pension

May 2017: Testing to Death: Which Public Pensions are Cash Flow Vulnerable?

Dec 2019: Merry Christmas! Have New Public Pensions Projections

Sep 2022: Labor Day 2022 Gift: Public Plans Projection Tool Update!

March 2023: Congrats to Lori Lightfoot! No Pension Failures on Her Watch!

July 2023: Chicago Pensions: Drowning, Not Waving

I will check out your spreadsheet soon. I did some work on government pensions, Jamaica, in a distant past.

I was curious if the "Last Year" column comes into play. On row 182, the value in that column is 2018, there is no amount for 2019 and there is an amount for 2020 (286,646). Is the model blind to the gap because we stop it before the gap? 2018?