Some Public Pensions Take (Small) Losses from FTX Disaster... But What About Other Alt Messes to Come?

Note: said alt messes may not come (this year)

When I saw the news about the FTX meltdown, I assumed some public pensions were exposed to it and would take losses.

So let’s see what we’ve heard so far:

ai-CIO: Ontario Teachers Pension Could Lose $95 Million on FTX Investment

Canada’s Ontario Teachers Pension Plan could lose as much as $95 million that it had invested in now bankrupt cryptocurrency exchange FTX.

In October of last year, the C$242.5 billion ($182.9 billion) pension fund announced that it had participated along with 68 other investors in a $420 million funding round for FTX Trading Ltd., which is the owner and operator of FTX.COM. The investment was made through OTPP’s C$8.2 billion Teachers’ Venture Growth platform.

So, the weasel word “could” covers a lot, but let us assume a $95 million loss.

Out of a portfolio of $183 billion.

That’s 0.05% of the portfolio.

To be sure, a loss sucks, but let us have this in perspective of total exposure.

Kansas City Star via Yahoo: Missouri state pension system lost money in crypto collapse tied to investment in FTX

The Missouri State Employees’ Retirement System lost roughly $1 million because a private equity firm it invested in was invested in FTX, the embattled cryptocurrency exchange that filed for bankruptcy last week.

T.J. Carlson, the pension fund’s chief investment officer, informed the retirement system’s board of the loss on Thursday, Missouri Treasurer Scott Fitzpatrick and another source familiar with the investment told The Star Friday.

Fitzpatrick is a member of the board because of his role as treasurer. He was elected Missouri auditor last week.

Fitzpatrick and the other source identified the private equity firm as BlackRock, a New York-based asset management firm, and said BlackRock had invested some of that money in FTX. The amount lost won’t affect MOSERS’ ability to pay pension benefits, Fitzpatrick said.

Candy Smith, a spokesperson for MOSERS, said in an email to The Star Friday that the system had roughly $1.2 million of exposure to FTX when the crypto company filed for bankruptcy. Smith said the loss is an estimated .01% of the MOSERS total portfolio exposure.

I want to point out the minimal exposure to FTX. Again.

I expect that other public pension plans will have also suffered some FTX losses, and they will likely have been relatively small compared to their total portfolios, as well. Most know to avoid concentration risk by not putting too much of an investment in a single “name”.

There may be a delay in the reporting not due to anything nefarious, but because the responsible folks took time off for Thanksgiving.

In general, investing for public pensions is supposed to be relatively sedate, so you’re not expecting 24/7 management support, especially not for something representing only 0.01% of the portfolio.

One investment isn’t the problem — a whole class of investments is

I wasn’t expecting any public pension to have a huge allocation sitting in FTX. It’s pretty alternative as alternative asset classes go (and, in general, we refer to alternative asset classes as “alts”).

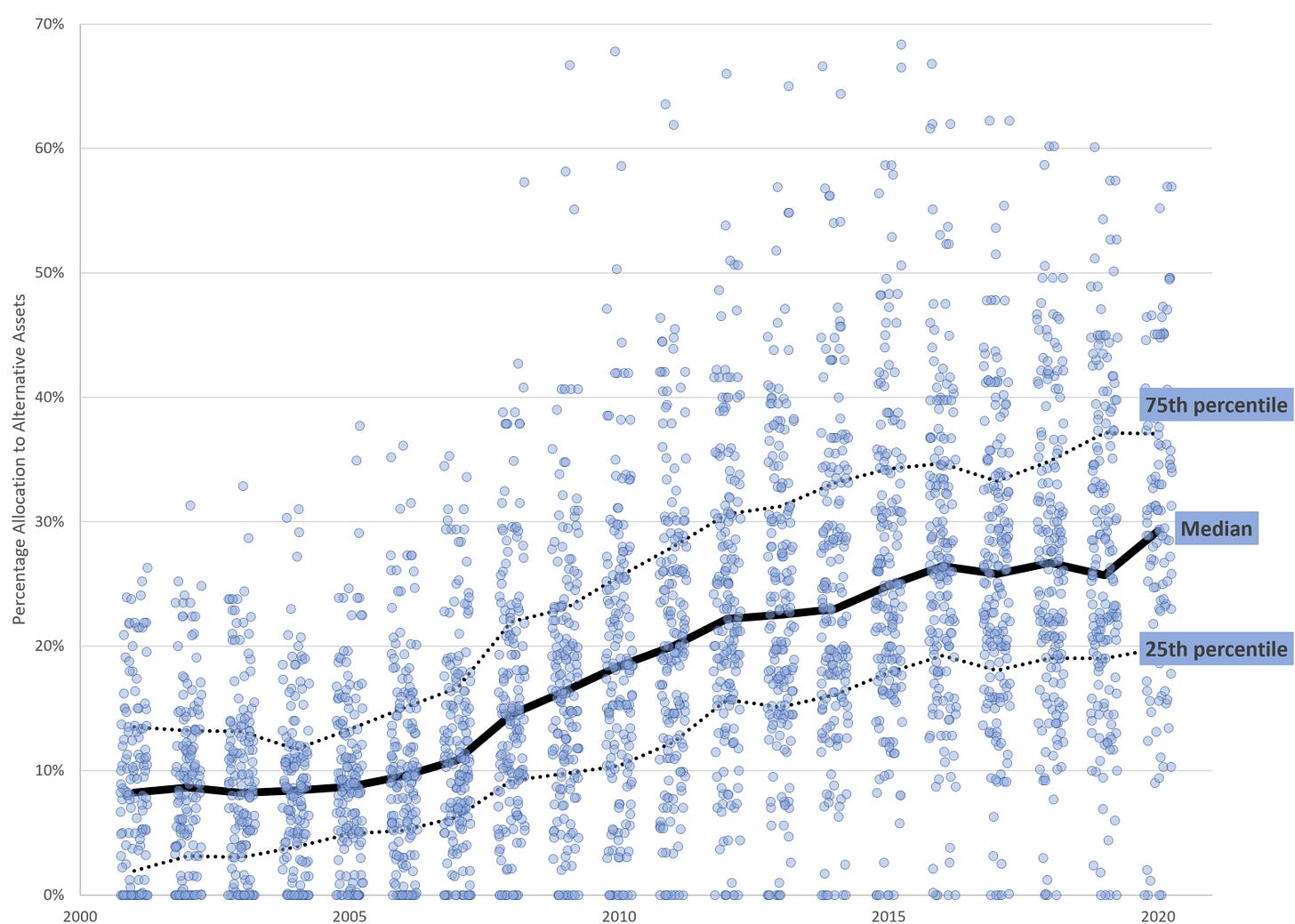

So here is the issue: public pensions have been increasing their allocation to alts by a lot in the past 20 years. They may not have large exposure to any one “name” (like FTX), but there is a lot of chasing yield (and trying to not require higher contributions.

And it is not clear to me that this level of allocation is appropriate for public pensions, nor are all alts created equal, nor do many boards of trustees have the wherewithal to provide appropriate oversight to this sort of allocation.

Here are some of my prior posts on public pensions and alts:

2021: Which Public Pension Funds Have the Highest Holdings of Alternative Assets? 2021 Edition

2020: Public Pensions, Leverage, and Private Equity: Calpers Goes Bold

2018: Alternative Assets and Pension Performance: A Dive into Data

2014: Public Pensions Watch: Don’t Go Chasing Waterfalls….or Alternative Asset Classes, pt 1 of many

August 2014: Public Pensions Watch: Dallas Pension Learns About Concentration Risk

September 2014: Public Pensions and Alternative Assets: Dallas Shows How It Can End

2017: Public Pension Assets: Our Funds were in Alternatives, and All We Got Were These Lousy High Fees

2015: Reddit-Public Pension Connection: Alternative Assets and Risk

2014: Public Pensions Watch: More Reactions to Calpers Pulling Out of Hedge Funds

2014: Public Pensions Watch: Alternative Assets, pt 8 of many — New Jersey followup

Let’s look at that 2021 post, which has the following graph:

These alternatives are neither regular publicly-traded stocks nor bonds. It’s stuff like private equity and hedge funds, and holdings in crypto.

By their very nature, they’re intended to be even higher risk than regular equities. The point is so that public pensions can reach those 7% – 8% target returns over the long haul.

Because if the public pension funds reduced those target returns to something a bit more feasible, and de-risked, then they would have to require higher contributions for the same pension promises they’re making now.

And they do not want to ask for higher contributions.

That’s the main motivation for getting into these asset classes, in my opinion.

Alternative opinion on alts

Now, I’ve been following David Sirota’s publications on this matter, and he’s got a different take: follow the money. That is, it’s all political corruption and asset management fees, back-scratching, yadda yadda.

I see that it’s an appealing message.

Let his colleague Matthew Cunningham-Cook lay it out: Wall Street Readies An Avalanche Of Lies

Public pension funds benefiting nearly 26 million Americans have invested $1.3 trillion in high-risk, high-fee “alternative” investments like private equity, hedge funds, and private real estate that have been wracked with corruption scandals and financial misconduct. Those pension funds could soon face a reckoning, as the downturn in the stock market spreads to these alternative investments, resulting in costly reductions of their estimated value and in turn, increased contributions from state and local governments to meet those losses.

But most public pension members and beneficiaries have no way of knowing the extent of distress facing their investments. That’s because public pension funds rely on valuations provided by the managers themselves — and thanks to secret contract clauses, managers can significantly massage and inflate their numbers.

….

Private equity and other alternative investments were originally peddled as vehicles that could deliver higher returns to investors, no matter the market environment, by taking over and transforming companies — often by loading them up with debt and laying off workers.

Such promises helped inspire public pensions to enter the space. Forty years ago, most public pension funds didn’t invest in private equity or hedge funds at all, instead pursuing far more orthodox investments in stocks and bonds. Now, public pensions have more than a trillion dollars invested in alternatives.

In total, public pensions supply more than a third of the capital to private equity, and they likely provide a similar share of the capital going to hedge funds and private real estate. And they are shoveling ever more money at the alternative investment industry, despite sky-high fees and returns that either meet or trail the broader markets.

….

President Joe Biden’s Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed modest reforms to the industry that would require increased transparency on performance, risk, and fees in the alternative investments space. But these reforms have been fiercely opposed by the industry.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) has proposed a much broader set of major reforms to the industry in the Stop Wall Street Looting Act, which among other things would rein in the amount of debt taken on by the industry and require new disclosures around fees and performance.

But considering the financial industry spent more than $340 million in the 2022 elections, the legislation faces an uphill battle in Congress. The private equity and investment industry has spent more than $13.8 million in lobbying in Washington this year alone.

I could go through the entire piece and rebut some of it, but indubitably some private equity deals are trying to boost their returns in the way described, and most involve leverage (that is, borrowing).

The whole point of private equity, of course, is to avoid all the registration & disclosure requirements of public equity (similarly for private debt), but that does not necessarily mean no disclosure to the investors.

All I’m hearing in the information above is that public pensions shouldn’t be allowed to invest in private assets.

How about try passing that law?

See how popular that one is.

Asset managers, obviously, want the assets under management to generate fees. But the public pension trustees mainly want plausible deniability with regard to their investment return targets. The moment one starts imposing requirements such that private equity is going to start behaving like public equity, well, there went that concept.

And they certainly wouldn’t be able to support paying such high asset management fees.

I think Sirota & crew and I are more or less on the same page on one point: we find the high allocations to alternative assets by public pensions to be very questionable.

Sirota’s outfit sees corruption. I know there has been pay-to-play, etc., in some situations. But it doesn’t require corruption to see this behavior.

It doesn’t require fraud for things to go wrong

I mentioned this way back when the real estate investments of Dallas Police and Fire imploded. I believe some federal fraud cases came out of that, but I’m not sure. I do remember saying it didn’t require fraud to fail at investing. It just required the normal vagaries of investments crapping out. But in the specific case of Dallas Police and Fire, there was too much concentration risk as well.

In the aftermath of the implosion, I wrote in 2017:

There might be fraud. But there might just be a high-cost asset management system because that’s the only way they could hit the 8% they were “guaranteeing” not only on the overall fund assets, but the discretionary amounts in the DROP benefit that retirees could pull out as lump sums.

Reminds me of the “good ole days” of Elliot Spitzer, who found ugly (but legal) practices in various asset management systems, and used that bad publicity to twist asset managers’ arms over something completely different.

Yes, having assets lose value, and paying high fees on top of that, really didn’t help the pension.

But that sort of result doesn’t require any criminality at all. But who knows — maybe there’s some fraud in there.

Similarly for private equity.

There are higher fees as it actually is more complicated to manage. It requires no fraud or other hanky-panky to explain that issue.

Just like public equity, they can also lose value.

How does one get a reliable value for private equity?

The issue is — what exactly is the value of these private equity investments?

If one is an individual, rich investor getting involved in private equity, you are very well aware that you won’t know the “true” value of your investment until you exit your position. Usually, that’s when you take the company public… or it fails completely. (Or it can be acquired by another private equity group or….) Basically, it’s when you cash out.

As an individual, you can make some estimates as to the value of your investment, but it doesn’t really matter. You don’t get taxed on unrealized capital gains (yet), so you’d estimate value just so you can keep score.

But pension funds do need a value before they cash out, so they can see how well they’re supporting their pension promises.

To value private equity holdings requires some assumptions, and that can be opaque. Obviously, it can be gamed in various ways.

Usually, the public pension funds aren’t independently valuing the private equity holdings on their own, but are relying on third parties who do not necessarily fully align in interest with the pensions. It’s generally the asset managers themselves providing the valuations, and yes, they’ll give the assumptions going into the valuations (they don’t necessarily keep those secret from investors – if they do, the investors should question their own legal counsel for getting them into such contracts).

It does call into question how much one can rely on the asset values for these alts.

A simple solution: STAY OUT

Maybe public pensions should stay out of private equity and other alts then. Maybe that’s the solution.

If they cannot provide appropriate oversight, if they need more reliable valuations, perhaps private equity and similar asset classes are not appropriate for them.

Because “we need higher returns!” is not a good enough excuse for getting into riskier assets.

They’ve got to support some very important liabilities. And, as the retirees of yet another town are finding out, when the assets get stressed there won’t necessarily be taxpayers there to make them whole.

I’m proposing the “no alts for public pensions” alternative because every “fix” I hear sounds like turning private equity, hedge funds, etc., into public equity. We’ve already got public equity. If the public pensions wanted to invest in public equity they could already do that.

How about just telling the public pension funds that they gotta stay out of the candy store?

Oh, and they need to contribute more to their funds.

Let me know how that goes.