Indiana Governor wants to give back taxpayer money, but I say give it to the teachers pension fund

(though the asset allocation looks a bit hairy to me)

The governor of Indiana posted this on Facebook yesterday:

Today I signed a proclamation calling a special session for the General Assembly to take action to return more than $1 billion of state reserves to Hoosier taxpayers.

This is the fastest, fairest and most efficient way to return taxpayers’ hard-earned money during a time of economic strain.

Indiana’s economy is growing and with more than $1 billion of revenue over current projections, Hoosier taxpayers deserve to have their money responsibly returned.I’m happy to be able to take this first step and look forward to signing this plan into law as soon as possible.

Then he linked to this: 2022 Special Session Proclamation

I understand why he may do something like this, and I should look at similar “rainy day funds” by states (and most states have them) and what they’re doing.

Yes, important elections are happening this year, so there’s the clear politics of the move. In addition, we may already be in a recession (it’s always called after the fact, because you need to measure GDP growth, and depending on who is doing the calling, it’s usually two consecutive quarters, so you’re usually 6 months behind the news.)

That said, the teachers pension fund in Indiana may need that money more.

The Indiana Teachers pension fund: not in great shape

I am not doing a deep dive into the Indiana Teachers pension fund right now, but merely taking two snapshots from the Public Pensions Database for the plan.

First snapshot: funded ratio.

The funded ratio is a ratio between the assets (numerator) and the total pension liability (current value of pension benefits already earned).

The funded ratio has been about 40%-50% forever for this plan. Those are the blue columns.

The red line is where most comparable pensions are in the U.S. There is a whole explanation where I can tell you how they should be close to 100%, not 75%, but let’s put that to one side right now.

The main thing is that the rest of the nation had fully-funded (i.e., 100% funded ratio plans) in 2001, at the end of the 1990s bull run, though those plans have been losing that status since then, in general.

But Indiana Teachers were nowhere near fully-funded in 2001. And since 2001, they’ve never really gotten much better than where they were. Even though we had a decade-long bull run, too. What up, Indiana Teachers?

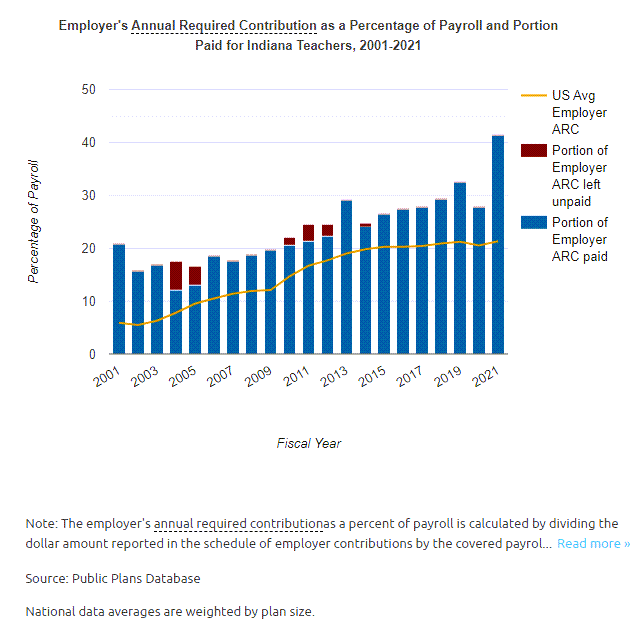

Snapshot 2 — how about contributions to the Indiana Teachers pension fund?

One potential explanation for the crappy funded ratio of the Indiana Teachers pension fund could be similar to such places like Illinois: deliberate undercontributions.

Let’s check it out:

The red bits of the bars are where they underfunded, officially.

Well, they did undercontribute a few of the years, but it wasn’t by much. It seems like they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing. Hmm.

I will point out the comparison here: the yellow line are comparable plans. Given that Indiana Teachers is underfunded, one would expect the required contributions to be at a higher level than other plans, which are at higher funded levels.

For Indiana Teachers to get anywhere near fully funded (which is saying that you will actually pay the pension benefits), they have to pay more to catch up. This gets to my recommendation: use that “extra” billion dollars to make an extra contribution to the teachers pension plan to help fill that hole a little more.

I will address a few objections to this option.

Objection One: Is it fair to transfer the extra tax money to the pension fund?

Fairness is in the eye of the beholder, but let’s get real: it is going to be difficult for the state of Indiana to default on paying the Indiana Teachers pension benefits.

The unfunded pension liability represents that past taxpayers did not pay enough for the pension benefits earned before now. Some of those past taxpayers are dead. Some have moved away. Some are still around to be taxed, to be sure, but as time moves on, more and more it’s new taxpayers and fewer old taxpayers.

No matter what, time marches on. The later you get taxpayers to pay for old services (i.e., the unfunded liabilities), the farther you’re getting away from the original people who benefited from the original services being paid for. That’s what pension benefits are, after all.

Paying off that debt sooner is better than trying to pay it off later.

That’s not been the standard pension finance practice, I know. But that standard practice has been showing huge cracks, don’t you think?

So, unless you’re going to default on that pension promise (which yes, I do know is an option, but let’s put that to one side), it makes sense to pay off that pension debt faster by taking this unexpected tax windfall and putting it into the pension fund.

Objection Two: Isn’t this as bad as doing a pension obligation bond?

Okay, I’m kind of making this one up (in that I haven’t heard anybody I know bringing up this objection. Because the people I know are generally financially savvy.)

However, I’ve been ragging on POBs lately, especially in my latest podcast episode and post on Providence, Rhode Island. From a distance, it could look similar, in that one takes a huge chunk of cash you weren’t expecting and then investing it…. but, that’s ignoring the huge “creating a new liability” part of POBs.

The real reason I wanted to put this in here is as a lead-in to my next part, related to an incipient recession, which I will deal with in a moment.

But I also want to talk about positioning when you have a windfall of cash and you see a huge financial crunch coming.

What do you do?

You de-leverage.

That is, you reduce your debt holdings, and increase your cash holdings.

When the federal government decided to throw money around like we were playing Monopoly on a quickly spinning lazy susan (I passed GO! I passed GO! I passed GO!), rather than try to stop them from sending me checks, I took it and paid down a bunch of debt. I de-leveraged. I got an interest-free loan from the government, as I knew I had to pay most of it back when tax time came (with no penalty – huzzah).

What Indiana could do is take this “excess” and make an extra contribution to the pension fund. It would de-leverage the state’s finances.

The last measured size of the pension fund was $13 billion, so a $1 billion contribution would actually be sizeable. It would make a big difference.

Objection Three: What about the timing? Do we want to shove in a bunch of money and then the market drops?

Well, you could always keep it in cash.

I noticed some disturbing things about the Indiana Teachers pension fund looking at its asset allocation, by the way. I will do an asset/liability/cash flow profile as I’ve done with other pension plans before in future posts.

The question as to whether the pension would actually use the cash wisely is a very good question.

But let’s consider the “What if you take this cash right before a huge market drop?” question in general — market timing is foolishness in general, and very foolish for pensions in particular. Thus the big foolishness of POBs.

If you don’t put the money in the fund, and the market drops, then the fund will drop from a lower point to begin with… and you’ll have to cash out to pay the benefits….. and you’ll be even more likely to be in an asset death spiral….

The money can run out, you know

I decided to see what the local news coverage of this potential tax refund was going to be, and I wanted to see what the tax refund amount would be per taxpayer. I’m in New York, not Indiana. I am not assuming anything.

Here is one piece: With talk of a new $225 tax refund for every Indiana taxpayer, what ever happened to the $125 refund promised last year?

Indiana has another budget surplus and Gov. Eric Holcomb wants it distributed to Hoosiers. Earlier this month, the governor announced he wanted to distribute $1 billion in tax relief to help Hoosiers deal with rising inflation. On Wednesday, he announced plans to call lawmakers back into a special session on July 6.

Under his plan, each taxpayer would receive about $225 — and that’s in addition to the $125 automatic tax refund that Holcomb pledged to each Indiana taxpayer at the end of last year.

The piece is about how long it takes for people to get the money. I’m not going to make fun of people wanting the money promised to them, or how little it is compared to, say, how much gasoline that could buy. I understand people wanting to get the money that was promised to them.

But this is my point: the people who were promised pensions also want to get that money. And it was a lot more than $225.

No, even if the funded ratio goes to zero — that doesn’t mean the pensions don’t get paid. It means they get paid out of current tax receipts (and any bond proceeds). But pension benefits are cash payments for former services, often services performed decades before. Taxpayers want to pay for services now. Paying more now to get less services is not going to make taxpayers happy.

I am arguing that the governor and legislature will make a larger impact by de-leveraging the state’s finances. That gives them more breathing room to figure out what to do with the pensions (because that’s not sustainable), and to quit this rinky-dink posturing.

So think about it, Indiana politicians. People aren’t going to vote for you due to $225 checks, I’m thinking.

I’m certainly not voting for any of the idiots who sent me about $3,000 that I had to send back at tax time.