Hochul's Congestion Pricing Hokey Pokey: More Reactions

Pulling away the football to try to avoid political consequences in 2024

I am so annoyed by Hochul’s bald political ploy on the timing of congestion pricing in Manhattan that I wrote some letters to editors of local Westchester County papers.

Here is one sample:

I agree with the public statement released by my Representative, Mike Lawler on the cynical pause/delay considered by Governor Hochul on the NYC congestion pricing plan.

Obviously, Gov. Hochul is considering pausing or delaying the implementation of the extra tolling on drivers in Manhattan in midtown and downtown until it's out of a "danger zone" for Democratic election prospects this fall.

As the delay in starting congestion pricing would cost the MTA in lost revenue, the New York Times reports that new business taxes in NYC are being considered. But, unless the congestion pricing plan is ended as opposed to delayed, when it's more convenient to start again, we would be looking at the congestion tax plus those new business taxes. Maybe in 2025?

I agree with Rep. Lawler -- the plan should be ended, not merely delayed or "paused".

- Mary Pat Campbell

North Salem, New York

I was referring to this statement by my Representative, Mike Lawler:

Congressman Mike Lawler Blasts Hochul's Blatant Election-Year Congestion Pricing Stunt

Today, Congressman Mike Lawler released the following statement after it was reported that Governor Kathy Hochul was examining a pause or delay to congestion pricing. Instead, it appears the Governor is examining a new tax on New York City businesses to make up for lost revenue from congestion pricing, showing that this was never about congestion, but rather always about more money for the MTA.

“Almost five months to the day before Election Day, Governor Hochul has suddenly realized how bad congestion pricing is polling in the suburbs and in New York City,” said Congressman Lawler (NY-17). “This cynical decision to ‘pause’ or ‘delay’ rather than cancel congestion pricing is nothing more than an election-year stunt. As I have said from the start — congestion pricing needs to be ended, not simply delayed.”

“Coming on the heels of Governor Hochul praising President Biden for scrambling to reinstate executive actions to secure the border that he foolishly rolled back almost 41 months ago, this vapid announcement by the Governor is yet another political ploy,” concluded Congressman Lawler (NY-17). “For the Governor to pump the brakes on congestion pricing now, while examining a new tax on businesses, shows that this was never about congestion, but rather it was always a money grab to shovel more taxpayer dollars into the endless pit that is the MTA’s constant waste, and corruption.”

Congressman Lawler is one of the most bipartisan members of the 118th Congress and represents New York's 17th Congressional District, which is just north of New York City and contains all or parts of Rockland, Putnam, Dutchess, and Westchester Counties.

You may be wondering why a member of the House of Representatives is commenting on Manhattan congestion pricing, given that it’s a “local” issue.

The final paragraph should give you an idea.

Lawler is a Republican, and there is a whole history here, and is linked to why Hochul may have been panicking re: the timing of this congestion charge.

Lawler was elected in 2022, as a result of a series of idiotic moves of the NY Democrats spanning a decade (but also because Lawler is very smart, a wonk, and works hard building coalitions.) Note that Lawler highlights his bipartisan record. He is not getting anywhere trying for a MAGA brand.

Post from 2022 where I explain the whole sequence of events:

Election Post-Mortem: New York Karma

While others are having the traditional post-election recriminations, I think there has not been enough of a look at how the Democrats screwed themselves over in New York because they wanted to make a “moral” gesture almost a decade ago. Because of that, I will have a Republican representative in Congress next year.

Lawler wasn’t the only Republican politician elected in NY in 2022, and a bunch are up for re-election. Interestingly, while the NY Democrats tried re-districting at various levels, they left Lawler’s district — which is my district — alone. It is very “purple”. But it is an interesting rural/suburban mix.

We’re pretty far out from NYC, but many people up here do work in Manhattan or own businesses there. We have direct interests in The City. We are not only affected by any proposed congestion charge, but also any proposed replacements for the lost MTA revenue.

The Actual Congestion Tolls

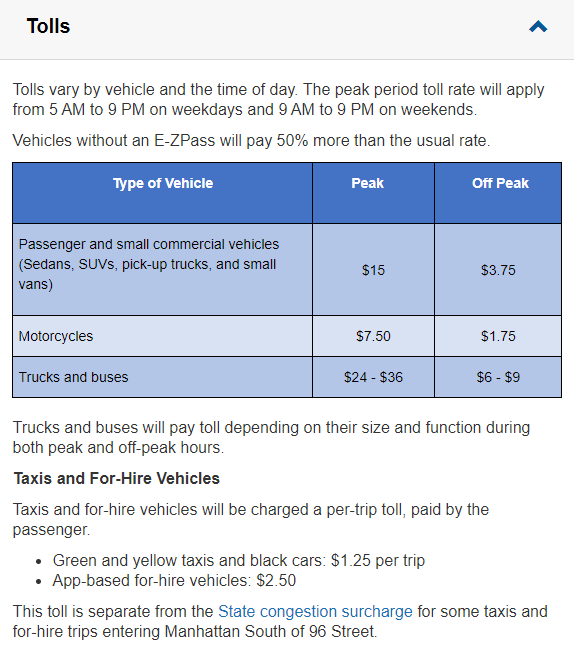

In my last post, I had a post from Time Out NY with the peak tolls listed, but this is a fairer representation of the congestion tolls:

There are adjustments for going through the tunnels, etc. etc., but I’m not going to worry about this stuff.

Note that the amounts never drop to zero, so if it’s a delivery truck for food to a grocery store in Chinatown, say, delivering material in the middle of the night so it’s not interfering with peak traffic times, they’re still getting charged a substantial amount.

The Lever: My Dude, Hochul Requires More Money Than $36K To Get Bought

Mind you, Hochul has managed to tick off about everybody with this last-minute move.

From the left, we have reporting from David Sirota’s The Lever:

Big Auto And The Death Of Traffic Congestion Reform

Before her eleventh-hour decision to reverse course and “indefinitely pause” a landmark plan to charge drivers higher prices for clogging up Manhattan streets, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) received $36,000 from lobbyists for state automobile dealers. Half of that money came from a lobbying group that opposed congestion pricing, citing “consequences for dealers and the thousands of people they employ.”

As recently as two weeks ago, Hochul told world leaders at the Global Economic Summit that investing in public transit like congestion pricing is “what cities are meant to do.”

But on Wednesday, Hochul declared traffic reform was not in the best interest of New Yorkers.

I will not quote the whole thing, but you can see my opinion in my section header: $36K is just not a lot of money in the scheme of NY electoral politics.

Hochul made this decision not because of lobbying, but because she thought Democrats would get hurt in areas like my district this fall in the congestion pricing policy was implemented this summer.

This is how The Lever reports it:

Hochul’s decision to stop the toll implementation was also allegedly motivated by the upcoming election and worries that the policy could hurt Democrats in the polls amid her growing presence on the national stage.

Hochul has no national stage presence.

This keeps happening to NY politicians. They keep getting fooled they have a chance on a “national stage.”

No. You do not: Cuomo, Schumer, Giuliani, etc.

Doesn’t matter if you are a Democrat or Republican — if you came up through NY local politics, ESPECIALLY ALBANY.

The country does not like NY state politics. I promise you.

You can put “allegedly” in there, but the NY Dems totally whiffed it in the House in 2022, and Hochul has a chance to at least not make it worse in 2024. Maybe they can claw back their 2024 losses.

Back to The Lever:

Hochul’s reversal comes as New York State struggles to adequately reduce its emissions. The state set “ambitious goals” in 2019 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent from 1990 levels by 2030 and by 85 percent from 1990 levels by 2050.

Currently, air pollutants in the city cause 2,400 deaths per year, along with thousands of emergency department visits and hospitalizations because of asthma and other heart and lung problems, according to an analysis published by the New York City government.

I call bullshit on the 2400 deaths/year. The link goes here: NYC Outdoor Air Quality page, and it just baldly asserts this.

But let us suppose it is true. There are some spots of bad air and bad asthma in the city… maybe some spots of Chinatown down in Manhattan would be one of the residential areas with trouble, but I’m going to guess more car-dependent and even bus-dependent areas of The Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens are worse.

Congestion pricing in the busiest part of Manhattan ain’t doing squat for the supposed 2400 deaths by air pollutants in NYC. Stop with the bullshit.

Aha! I found their data dashboard — I WILL RETURN with another post on this for Mortality with Meep another time.

[rubbing my hands…. YES!]

Megan McArdle on Why Congestion Pricing is Doomed

At the Washington Post: People hate traffic. They also hate this great way to clear it

Subhed: If it can’t be done in New York City, it probably can’t be done anywhere else in America.

The piece is pretty short, but here are a couple of excerpts:

The first paragraph explains why congestion pricing of roads is good. The second explains why it’s a nonstarter in the United States, as New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) demonstrated when she decided to “pause” (pronounced “kill”) a New York City congestion pricing program that was supposed to take effect this month. If congestion pricing can’t be done in Manhattan, it seems safe to say it can’t be done anywhere else in America, either.

….

New York’s proposed system would offer low-income drivers a substantial discount. But that mitigation would solve a problem, not the problem, which is that rationing by prices made a lot of existing drivers worse off. Sure, when they drove into the city, they would spend less time sitting in traffic. But just as road pricing is easiest on people who find it least painful to pay the tolls, rationing by queuing is easiest on people who find it the least painful to spend time in traffic. In a place as choked with cars as Manhattan, the population of drivers is skewed toward such people. Those who find it unbearable cram themselves onto commuter trains, or move to some less-congested metro area.

So, here’s the deal: who, exactly, drives below 60th Street in Manhattan?

When I moved to Manhattan back in 1996, for grad school, I was told by multiple people not to take my car. I was moving into NYU housing that was provided to grad students… and it did not come with parking benefits. Parking was hella expensive. And there was no way in hell I would drive in NYC.

Other than driving along the edge of Manhattan to get to the George Washington Bridge, or sometimes driving to JFK or LaGuardia, I refuse to drive in the city. Holy crap no. I take the train. I don’t even like cabs. They suck.

It would be nice to know what the distribution of the different vehicle types are now in usage, though. I found this report from 2019, but no data on how many trucks, how many cabs, etc.

I don’t know what other people are thinking about with respect to the congestion pricing, but I’m thinking of the delivery trucks.

Having the congestion pricing would affect the restaurants, museums, and other venues I like visiting in the city — their suppliers would have higher costs, and yes, people like me would ultimately bear those costs. That’s what I’m thinking about.

Other people may be thinking about higher costs on their cab and Uber rides.

A few nuts may be thinking about higher costs when/if they drive into the city (those crazy folks).

Then there are lower-income people who have a lot of time to wait in traffic, as McArdle mentions above. They may drive around the city for errands, and have time to wait for city parking spaces, and may be living in less-popular areas as well. They say these folks get fee reductions, but that involves applying for that… and there may be issues for people to go through that process.

Anyway, I can see why this is unpopular except among policy wonks.

Comments from the Truckers

FleetOwner: New York City’s congestion fees plan finds more trucking pushback

In late May, the Trucking Association of New York, a trade group representing delivery companies, filed a lawsuit, claiming that the steep fees would ultimately hurt small and midsize businesses and their customers. At least five to seven other entities were in the process of taking additional legal action against the city’s congestion plan.

Local businesses were already feeling the pinch as the proposed pricing plan left businesses wondering how to navigate the new fees while remaining profitable. A Brooklyn-based HVAC service company had already started alerting its customers in the Congestion Relief Zone that they would see a $15 surcharge for all work orders to compensate for the new fees. Other companies in the zone suggested slashed hours, staff reductions, and layoffs to offset the fees and expected decrease in customers and sales. New Yorkers were also grappling with how they would traverse their home turf. A consumer poll conducted by Siena College in April 2024 found that 63% of residents opposed the MTA’s congestion pricing plan, with 17% revealing they’d find other ways to travel around Manhattan.

Experts say a “domino effect” may occur if this plan or a similar one is enacted in the future, driving up prices that New Yorkers pay for basic goods and services—an unwelcome price hike in one of the world’s most expensive cities. If the plan moves forward at some point, many trucking companies will likely raise their delivery rates, forcing local businesses to increase product prices in response—eventually hitting consumers’ wallets.

People in Manhattan, even if they’re not driving around cars themselves, know they’re dependent on delivery trucks bringing in their food.

They’re not idiots.

Everybody who lives in that area knows that the congestion pricing would raise their living expenses even if they personally got exemptions from the charges for using a vehicle directly.

The Public Finance Impact

All that said, the MTA had already counted on $1 billion per year being available from that congestion pricing project.

Cutting this revenue source off would have consequences.

Second Avenue Subway Project May Be Affected

Marc Joffe On LinkedIn: Hochul’s Reversal on Congestion Pricing Jeopardizes Second Avenue Subway

Also, MTA had plans for the congestion pricing revenue which are now imperiled. The intention was to issue a $15 billion municipal bond whose debt service would be backed by the estimated $1 billion of annual congestion pricing revenue pricing (state legislators briefly considered alternative taxes to replace the congestion pricing revenue but adjourned on June 7th without taking action). The bond proceeds were to be spent on transit projects listed in the MTA’s Capital Plan.

….

But the plan also includes costly additions to MTA’s transit infrastructure, such as a three-station, $7.7 billion extension of the Second Avenue Subway. As I discussed previously, the case for this project has weakened in the wake of COVID-19, which reduced overcrowding on the nearby Lexington Avenue Line.

Hochul’s reversal on congestion pricing could jeopardize federal funding for this project. As retired Federal Transit Administration (FTA) official Larry Penner told me:

MTA previously accepted the terms and conditions within the FTA Full Funding Grant Agreement (FFGA) grant offer. This included a legal commitment that the $4.3 billion in local share was real, secure and in place. FTA caps its funding at $3.4 billion based upon the MTA's commitment of a secure $4.3 billion local share. MTA's local share was based upon implementation of Congestion Pricing.

MTA Financial Gridlock

CNBC: With congestion pricing stop, New York City enters new era of economic gridlock

Many opponents view Hochul’s sudden announcement delaying the policy months before the elections as a political move to ensure reelection and favor from local politicians in swing districts. That’s nothing new, Wylde noted, referencing a commuter tax that was eliminated decades ago at a time when Democratic seats were “up for grabs” in the state legislature. “This is the same kind of situation,” she said. “It is a suburban backlash and concerns about candidates, and in particular, Democratic candidates. The politics of it are chronic and there is not a lot we can do about it from the business side.”

Wylde hopes the delay is temporary, and the MTA can move ahead with their plans for leveraging the increased funding. Everywhere that congestion pricing has been introduced globally, she said, it has worked, from London to Stockholm to Singapore. “There’s an opposition going in, and then when people see the results they’re thrilled. Because your cost of doing business goes down substantially. ... The quality of life is much better after congestion pricing.”

A former colleague of congestion pricing pioneer Vickrey at Columbia University, Dr. Steven Cohen, Senior Vice Dean at Columbia, wrote in a recent post that unintended consequences and need for policy revision are implicit in any new undertaking, but the city and its commuters could look to big business for the proof that the concept is effective.

“There [undoubtedly] will be unanticipated negative impacts of the new policy. Every new policy and product have downsides you can’t predict without experience. ... The point is we can adjust policies and products to address negative impacts. But congestion pricing’s underlying policy design is sound. A congestion fee will generate revenue for mass transit and reduce traffic jams. Surge pricing works. It works for Uber and it works for JetBlue.”

According to that piece, only 4% of city workers drive into the city.

Sounds about correct to me.

The main impacts would be on cabs and delivery trucks, making a lot of the midtown business unpleasant not for commutes, but to conduct meetings you need catered, and that sort of thing. I can think through all sorts of impacts.

Again, the unpopularity was not because a huge number of people themselves drive, but they know how vehicles getting around in that area affect their own lives.

It polled poorly, and extremely poorly among the “swing” folks in commuter areas like mine.

Hochul decided to suspend congestion pricing as public polling shows the cost of living in New York becoming a top concern for voters. A Siena College poll released in April found 63 percent of voters statewide opposed the plan. In suburbs that will be key to House races this year, 72 percent of voters said they opposed it, the poll found.

No, it wasn’t really about environmental impacts.

Yes, it was about revenue.

Yes, it was about traffic.

And the timing of this is about politics.

The question is where the revenue replacement will come from… if anywhere?