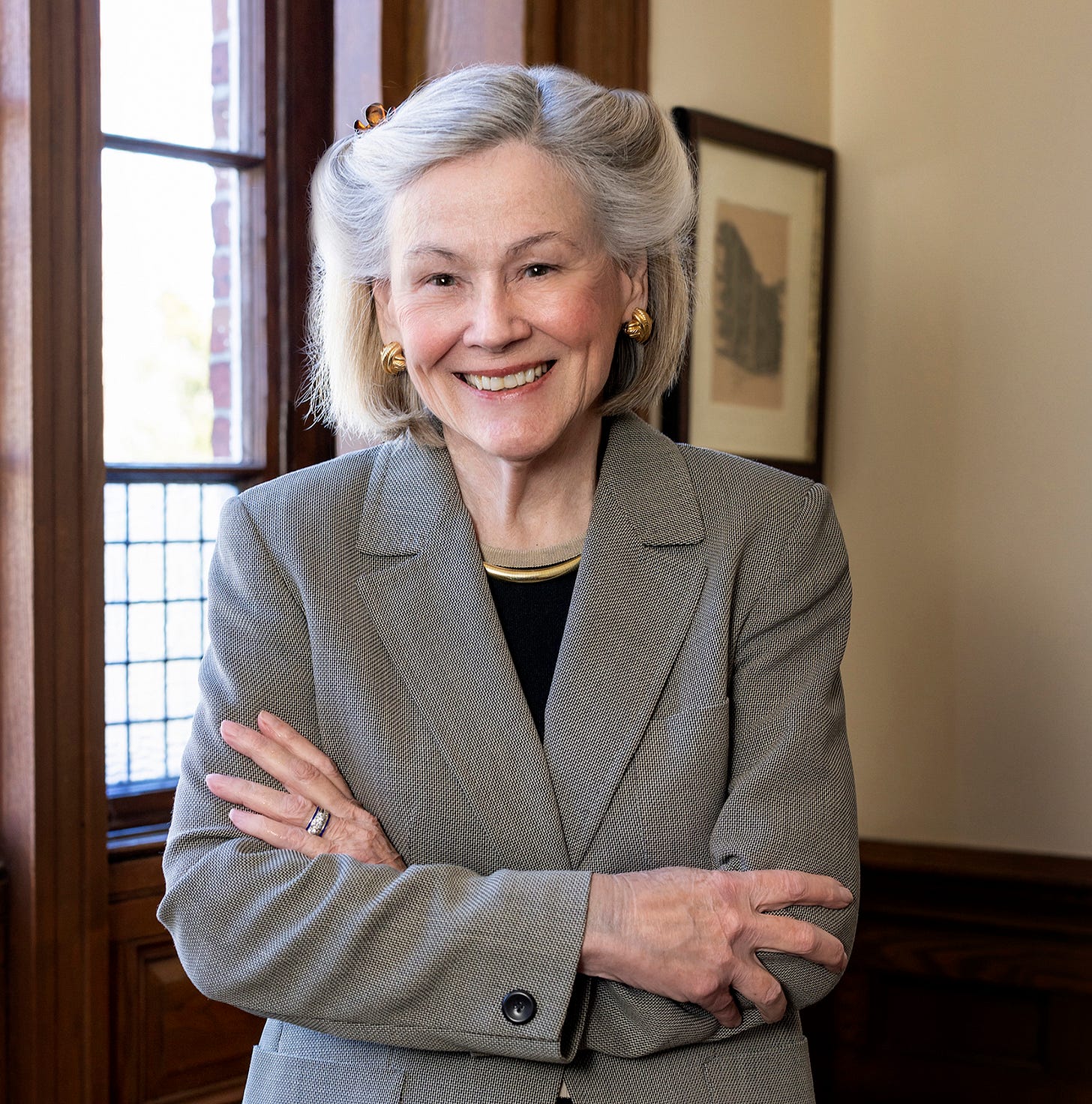

Happy Retirement, Alicia Munnell!

Well beyond the normal retirement age -- have some frivolous times!

NY Times today: Alicia Munnell, Founder of a Retirement Research Hub, Is Retiring

If there’s anyone ready for retirement, it’s Alicia Munnell. She founded and has been running the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College since 1998, making it one of the leading nonpartisan think tanks examining how American workers can thrive after they leave their jobs.

“I’m very proud of this center,” Ms. Munnell said. “We have great people and really good academics who really care.”

She served on former President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers and was assistant secretary of the Treasury for economic policy in his administration. Previously, she spent 20 years at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, where she rose to become senior vice president and director of research.

Ms. Munnell, 82, is retiring at the end of December, when Andrew Eschtruth, the center’s deputy director, will take over. Before she departs, she talked about her career and the projected shortfall that would leave Social Security, the cornerstone of the American retirement system, unable to pay full scheduled benefits after 2033. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

I am not going to “excerpt” (aka copy) the entire interview (or at least the version I’m looking at).

One comment: age 82 is well beyond the “normal” retirement age in many (most) pension systems. However, it’s not unusual in academia, which has no required retirement ages and often has no required duties for senior faculty (so they can do whatever they want). Usually, people retire from academia when their health precludes them from doing their main projects.

Another suggestion to cope with the projected shortfall is to raise the age for collecting Social Security. Would that work?

Proposals to delay the full retirement age are based on the notion that life expectancy has increased. Life expectancy has increased, but primarily for those in the top half of the income distribution. People with lower levels of education, minorities, particularly Blacks and other vulnerable groups, haven’t seen the gains in life expectancy over the last two, three or four decades.

I’m actually for increasing the full retirement age for those who can work longer. For people in the top half of the income distribution, you could figure out what their benefits would average and index it to their monthly earnings, then phase in a big increase in the retirement age for people in the top 10 percent of earnings, a smaller increase for people in the next 10 percent, graduated on down so there would be no increase for people below the average. It would make benefits more progressive and make the system fairer.

I cut out a couple of questions on removing the wage cap on Social Security (to raise revenue) without raising benefits. Munnell is against de-coupling the payroll taxes paid and the benefit formula.

Her proposed “fix” of a different “full retirement age” for people with different earnings histories would have troubles…. but you know what? It’s her retirement party, so let’s let her put her ideas out there.

Social Security is called the “third rail” of American politics, and retirees are potent and active voters. Is it realistic to think that sometime after 2033 Congress would cut retirement benefits?

Raising revenue would be politically a very hard thing to do, because it means raising taxes now for something that won’t happen until 2033. But I think it’s harder to conceive of the situation where Congress would allow across-the-board cuts to retirement benefits.

People love this program and are willing to pay for it. I think if you just be straight with the American people about what needs to be done, there would be support for fixing it. This tendency to postpone solving the problem makes a lot of people nervous about a source of support that they rely on very strongly.

I’m biting my tongue over things I could say about something happening in 2033, supposedly being far away. I’m 50 years old, so things look different to me.

That said, I think nothing will be done until a couple years before the Trust Fund runs out, so yes, maybe she does have a point.

You’ve written that the key is working as long as you can. Even now, you’ll be staying on for a year as a senior adviser. It would seem that you certainly practice what you preach.

Yes, I’m 82, but I know that I have just a wonderful job, an easy job, a job I love. So it’s fun for me to work. Other people have hard, physically demanding jobs or work in an organization where they’re being forced out, so I am not advocating this for everyone.

….

Financial planners stress that people need to have an idea of what their retirement lifestyle will be. Do you have plans?

If you’re talking to somebody who’s retiring at 65, you can ask them really earnestly, “What are you going to do?” But I’m retiring at 82, so do you have to keep doing serious things or can I watch Netflix during the day and become a better cook? I just don’t know if I may want to go back to my roots and be frivolous again.

She absolutely has a point here. This is somewhat the plan I have: try to work as long as I can, and then it will be frivolity. Nothing but opera and sumo.

Alicia H. Munnell Profile at Boston College

Alicia H. Munnell

Director

Peter F. Drucker Professor of Management Sciences

Alicia H. Munnell is the Peter F. Drucker Professor of Management Sciences at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management. She also serves as the director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Before joining Boston College in 1997, Alicia Munnell was a member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (1995-1997) and assistant secretary of the Treasury for economic policy (1993-1995). Previously, she spent 20 years at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (1973-1993), where she became senior vice president and director of research in 1984. She has published many articles, authored numerous books, and edited several volumes on tax policy, Social Security, public and private pensions, and productivity.

Alicia Munnell was co-founder and first president of the National Academy of Social Insurance and is currently a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine. She is a member of the board of the National Bureau of Economic Research and the Pension Rights Center. In 2007, she was awarded the International INA Prize for Insurance Sciences by the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei in Rome. In 2009, she received the Robert M. Ball Award for Outstanding Achievements in Social Insurance from the National Academy of Social Insurance. In 2015, she chaired the U.S. Social Security Advisory Board’s Technical Panel on Assumptions and Methods.

Alicia Munnell earned her B.A. from Wellesley College, an M.A. from Boston University, and her Ph.D. from Harvard University.

Alicia Munnell Selected Publications

10 December 2024: The Social Security Fairness Act Is a Bad Idea

On November 12, the House passed the Social Security Fairness Act to repeal the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP), which reduces Social Security benefits for workers receiving significant government pensions from jobs not covered by Social Security. A companion provision – the Government Pension Offset (GPO) – makes similar adjustments for their spouses and survivors.

Since their enactment in 1983, the WEP and GPO have infuriated state and local employees, who feel they are unfairly being denied benefits. In fact, these provisions are a legitimate – if imperfect – effort to solve an equity issue that arises because 25-30 percent of state and local workers are not covered by Social Security.

Clearly, we who support some form of adjustment have not done a very good job making the case. Let me try one more time. Essentially, state/local workers who spend their career not covered by the Social Security system but gain some minimum coverage either on side jobs or after retirement look like “low earners” to Social Security. As “low earners,” they profit from the progressive benefit structure, which was designed to help those with a lifetime of low pay – not those who earned a good living in jobs not covered by Social Security.

….

In the end, of course, the long-run fix is to extend Social Security coverage to all state and local workers, which would both offer better protection for workers and eliminate the equity problem.

17 Dec 2024: A Social Security Payroll Tax Increase Should Be Part of the Solution

But the increase should be small and gradual.

Enough with politics. It’s time to get back to solving problems. Not surprisingly – given my slant on the world – the problem I care most about is fixing Social Security. But in an attempt to protect lower-income households, President Biden committed to never raising taxes on households earning less than $400,000. This prohibition turned reasonable plans for a comprehensive solution into silly proposals where benefit expansions would sunset after a few years.

My view is that a modest increase in the payroll tax rate should be part of any package to close Social Security’s 75-year shortfall. Indeed, the Social Security actuaries’ scoring of options shows that very gradually increasing the employee and employer payroll tax rate each by 1 percentage point (from 6.2 percent today to 7.2 percent in 2049) would cut the 75-year deficit from 3.5 percent of taxable payroll to 1.5 percent. Of course, other components would be required, such as raising the taxable earnings base, expanding coverage to state and local workers, and perhaps investing some trust fund reserves in equities. And if 1 percentage point is too much of a payroll tax increase, then cut it in half. But some increase in the rate should at least be open for discussion.

17 Jan 2024: A Multiple Employer Plans Primer: Exploring Their Potential to Close the Coverage Gap (co-written with Anqi Chen)

The report’s key findings are:

About half of private sector workers are not covered by an employer retirement plan at any given time; this coverage gap is driven by small firms.

To encourage more small firms to adopt plans, policymakers have made it easier to participate in Multiple Employer Plans (MEPs).

MEPs reduce the administrative burden and fiduciary responsibilities of a stand-alone plan, and – in theory – could be cheaper.

But it’s not clear that they do cost less, and any such assessment should consider employee – as well as employer – fees.

Overall, while MEPs could be attractive, adoption may be slow due to unfamiliarity with the product and uncertainty over any cost advantage.

19 Nov 2014: New tool could help public pensions stay on course

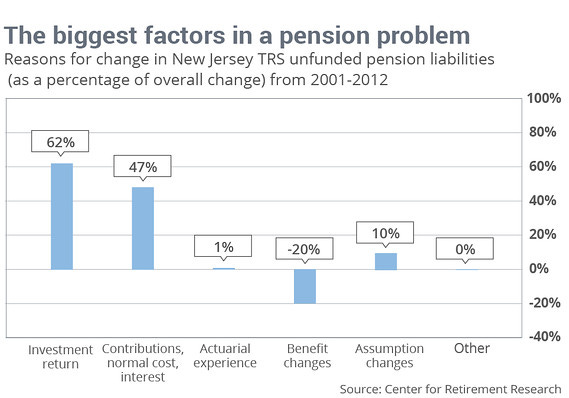

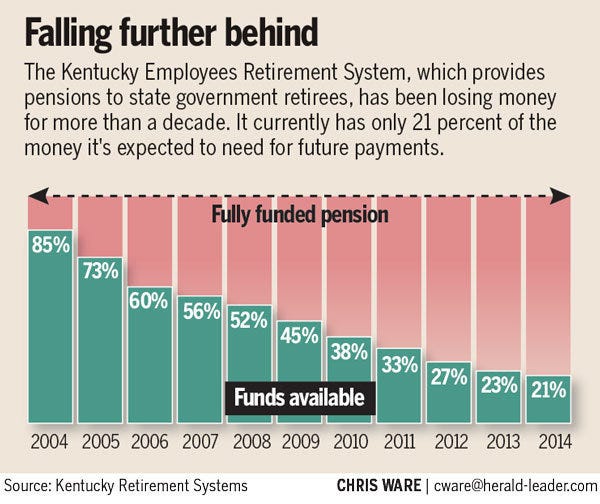

While we can’t solve all problems, my colleagues and I would like to toss a proposal for a new analytic tool into the mix. It is not so much prescriptive, but rather will make clear to the plan sponsor the extent to which the plan is making any funding progress. This tool would highlight, on a historical basis, the specific reasons why the unfunded liability has been growing. Every plan’s actuarial valuation reports the Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liability (UAAL), the change in the UAAL from the prior year, and some information on the factors that led to the change. The task is to simply combine these annual changes over an extended time period.

That last piece was linked and quoted in my November 2014 post on my old website: Public Pensions: What's so Bad about 80%? (and coming attractions), which I re-ran as a STUMP Classic:

STUMP Classics: What's So Bad About 80% Fundedness?

The following originally ran in November 2014: Public Pensions: What’s so Bad about 80%? (and coming attractions). This is an edited version [I updated a few links and did text clean up]/

Alicia Munnell and her colleagues at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College built one of my favorite public pension resources: The Public Plans Database.

Click on the About Us > People links:

I have been using this resource for years. It has taken a lot of manual work for all involved, I know — I have seen it built up over the years. I know Munnell and others have been able to analyze their data set as a result, but I am so happy they shared it with the rest of us.

Thanks, Alicia Munnell!

Enjoy a frivolous retirement!