Deaths from Heat and Cold: Update for U.S. 1999-2023

Also, pushing the record back to 1968 to see if there is anything interesting

The following was brought to my attention:

Heat killed a record number of Americans last year

As the planet warms, heat-related deaths are increasing in the U.S., according to a new study that looked at federally reported data since 1999.

More Americans died from heat in 2023 than any year in over two decades of records, according to the findings published Monday. Last year was also the globe's hottest year on record, the latest grim milestone in a warming trend fueled by climate change.

The study, published in the American Medical Association journal JAMA, found that 2,325 people died from heat in 2023. Researchers admit that number is likely an undercount. The research adjusted for a growing and aging U.S. population, and found the death toll was still staggering.

….

Howard – along with researchers from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, in Maryland, and Pennsylvania State University – examined death certificate data between 1999 and 2023. Deaths were counted if heat was listed as an underlying or contributing cause of death.

Reported deaths remained relatively flat until around 2016, when the number of people dying began increasing, in what Howard, who studies health effects from extreme weather, calls a “hockey stick.” The hockey stick analogy has been used to describe warming global temperatures caused by climate change, where temperatures have swooped upward at alarming rates in recent years.

This was in USA Today (today), linking to the JAMA Network piece:

Trends of Heat-Related Deaths in the US, 1999-2023

Jeffrey T. Howard, PhD1; Nicole Androne, MS1; Karl C. Alcover, PhD2; et alAlexis R. Santos-Lozada, PhD3

Author Affiliations Article Information

JAMA. Published online August 26, 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.16386

Here’s their method:

Methods

We analyzed all deaths from 1999 to 2023 in which the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision code was P81 (environmental hyperthermia of newborn), T67 (effects of heat and light), or X30 (exposure to excessive natural heat) as either the underlying cause or as a contributing cause of death, as recorded in the Multiple Cause of Death file. Data were accessed through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER platform,5 which combines death counts with population estimates produced by the US Census Bureau to calculate mortality rates. For each year, we extracted age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) per 100 000 person-years for heat-related deaths. The AAMR accounts for differences due to age structures, allowing direct comparisons across time. The approach of analyzing cause-specific mortality rates rather than excess mortality is warranted because the excess mortality methodology is subject to confounding from the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2023. This study used publicly available, deidentified aggregate data; thus, it was not considered human subjects research.

Joinpoint version 5.2.0 (National Cancer Institute) regression6 was used to analyze AAMRs to assess trends and determine elbow points where the trend began to shift to a new trajectory. Results of joinpoint analyses are reported as average annual percentage change (AAPC) in rates with 95% CIs. Statistical significance was defined as 2-sided P < .05. Data were visualized with R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Here’s their graph:

Wonder what happened in 1999.

Hmmm. Maybe I should look at pre-1999 years. I remember, as a child, in Savannah, Georgia, in the 1970s, often there was no A/C.

Hmmm.

Heat deaths on STUMP

Now, I’ve covered this topic a few times before, and here is the most recent:

Deaths from Heat and Cold: Deception and Update for U.S. 1999-2022

First, an attempt to deceive… or just incompetent graph-making.

I generally only use underlying cause of death, but so you can see the difference, I will grab the data both ways and graph that so you can see the distinction.

(I will also pull the cold deaths: X31 – Exposure to excessive natural cold, but show those results in a bit).

For UCD, T67 is never a code. It’s only ever a contributing cause.

I didn’t use P81, by the way, which includes some deaths we don’t want, but P81.0, which is environmental excessive heat. The spreadsheet with all the original data and the graphs is available at the end of this post. The data source is CDC WONDER, with data downloaded today.

Anyway, here is a stacked column graph result:

That was all just to show that the ratio of “contributing cause” only vs UCD (underlying cause of death) is pretty steady for this type of death, so I’m just going to stick to UCD, as I usually do.

Yes, my numbers will not exactly match theirs, but their point on trend will be the same. Also, I will drop P81.0, as CDC WONDER returned exactly 0 results for that for 1999-2020. I’m not bothering with that.

Heat Deaths vs. Cold Deaths 1999-2023

For this, I’m just showing the rates, because I want to show counts and rates for a longer period in a moment.

For most years, deaths due to cold are higher than deaths due to heat.

When you see the age and geographic distribution of the deaths, it becomes a bit more understandable.

Counts by age group:

Rates by age group:

The young and old are vulnerable to heat deaths, but the old are particularly vulnerable to death by cold.

Geographic comparisons of heat and cold deaths

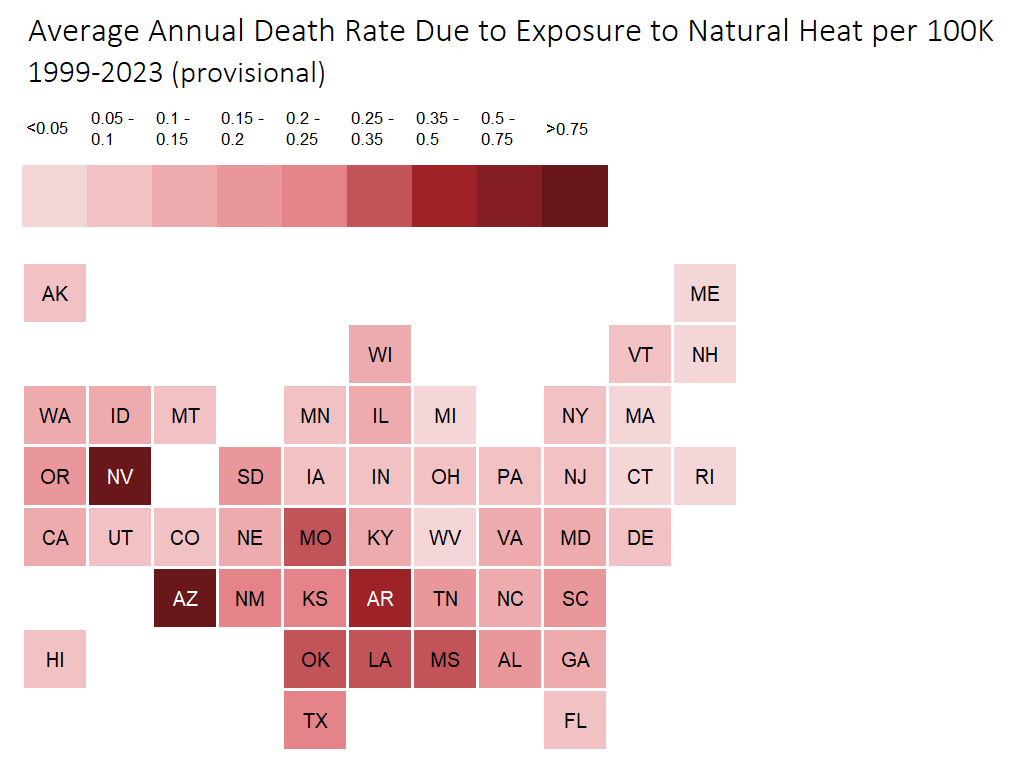

But let us look at the geographic spread. This is by rate alone, so these are comparable:

Some states have so few heat deaths recorded that they are missing from this map. All states had at least 10 deaths due to excessive cold in the period, so no problem.

Pushing back the history to 1968

CDC Wonder has data easily accessible going back to 1968, so I decided to grab the deaths due to excessive heat or cold.

Let’s graph the counts, to keep things simple, even though the population changed a lot in this period. The accessibility of air conditioning also changed a lot in this period.

Holy crap, what happened in 1980?

Remembering the historic heat wave of 1980

The summer of 1980 was one for the record books when it came to extreme heat. Nearly 400 Missourians died from the high temperatures during the three-month heat wave.

In addition to the lives lost, the American Meteorological Society says the cost of the hot, dry summer of 1980 was close to $16 billion. That summer will go down as one of the costliest and deadliest natural disasters in US history.

It is listed among the top U.S. deadly disasters, with 1,260 excess heat deaths directly attributed to the heat wave.

It's also among NOAA’s billion-dollar disasters. At the database, they estimated 10K excess deaths (including the heat deaths), and $40.5 billion in inflation-adjusted damages.

On June 24, 1980, temperatures started to creep above 90° and steadily increased through the beginning of August, before finally cooling down at the end of September. Nearly three months of unbearable heat wreaked havoc on the Midwest and Southern Plains.

From July 13 to August 8, 1980, 21 days were 100° or more. On July 31, 1980, Springfield reached 105°, the hottest temperature of the year.

The 1980 heat wave resulted in 389 heat-related deaths in Missouri. According to NOAA, over 87% of the deaths occurred during a two-week period, July 8-21, when 339 people died. In St. Louis, more than 150 people died and in Kansas City, 176 deaths were reported.

It became difficult for people to escape the heat. According to the Air-Conditioning & Refrigeration Institute (ARI), 43% of American homes were without any kind of air conditioning in 1980.

Something to think about.

And the NYT is demonizing air conditioning https://t.co/Yd3NNxQPyl

Would love to see US maps by county