What Are (and Were) the Chances of Living to 100?

What about life expectancy getting to be 100?

Recently, we’ve had a spate of notable deaths in the U.S. at fairly advanced ages:

Just a few I noted:

Norman Lear, 12/5/2023, died aged 101

Charlie Munger, 11/28/2023, died aged 99

Rosalyn Carter, 11/19/2023, died aged 96

Sandra Day O’Connor, 12/1/2023, died aged 93

Henry Kissinger, 11/29/2023, died aged 100

The Society of Actuaries has its international Living to 100 Symposium, and while I’ve never been able to attend, I read their papers. I may demo their longevity illustrators in a post (but not this one).

Also, if my Pop-pop were still alive, he’d be turning 100 this year.

So I was thinking: what are the chances of living to 100 from birth?

Pick the correct life table: cohort tables

Before I give you one estimate of the probabilities (and this comes from the Social Security Administration actuaries, who give input to the annual Trustees report), I want to point out what mortality tables … or “life tables” you want to look at: cohort tables.

These are tables with information organized based on the year people were born.

For most of my recent mortality analyses, I use calendar year mortality tables. This leads to all sorts of misunderstandings (especially with respect to life expectancy… which I will get to by the end of this post.)

The Social Security Administration helpfully shares the life tables from its annual trustees report.

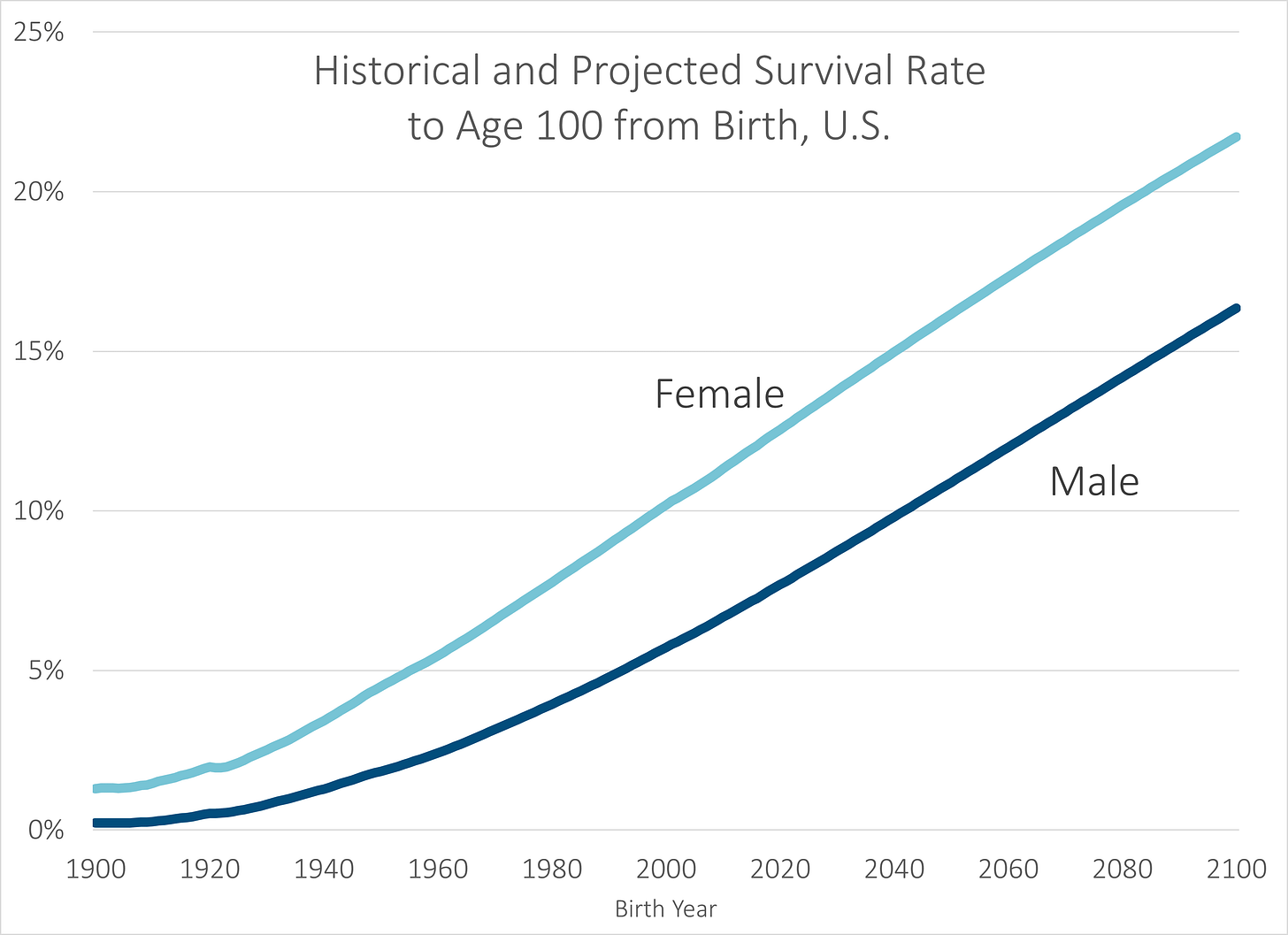

Here’s the page for the 2023 tables, which is what I used for this post. The tables are by sex and cover birth years 1900-2100. Obviously, this is a mix between historical actual experience and projections for years yet to come - not only for people yet to be born, but for cohorts like mine, where most of us are still alive.

Probability of Reaching Age 100

First, the portion of these curves that is based on full, actual historical experience, at most, would be birth years 1900-1922.

Note the little dip in the female curve around birth year 1920? That’s COVID. There’s one in the male curve, too, just more difficult to eyeball.

There is some partial experience in birth years 1923-2020, but as it gets closer to present-day, the more of a projection it is. Actuaries use what are called projection scales - these have actually worked fairly well (absent pandemics… -cough-).

According to the projection, they’re expecting about 5% of American females born in 1960 and 2% of American males born in 1960 to live to age 100.

Then, they project that 15% of females and 10% of males born in 2040 to live to 100.

Maybe you can see why Social Security has some strains. (More on that in a later post.)

Expectations about life expectancy

While I was putting this post together, Paul Fairie posted one of his many compilations of old news stories, this time, predictions about the year 2024 from the year 1924.

While some people do keep trying to push the idea that 75 isn’t all that old (Boomers, you’re old), and the UK does have a higher (period) life expectancy than the U.S. (for now), no, no country has 100 as a cohort life expectancy.

Using the same mortality projections as above by birth year, here are life expectancies from birth:

The improvement in cohort life expectancy was very steep from birth year 1900 to about 1950 and then the slope becomes shallower.

Some of that is from improvement in infant mortality, and some from reduction in smoking. But if you look at the curves, I think what’s going on here is that up to 1950 is heavily based on actual experience (thus the ragged look of the curve) and they decided to assume less improvement past 1950.

I think they decided to be more conservative in assumptions in longevity improvement for future generations, thus the gentler increases.

But…. I’ve also seen that mortality improvements have leveled off in recent years, so they may very well have a point with that bend. Certain mortality trends have actually worsened since 2010, and not just the drug overdoses that I go on about so much.

Sidebar: Cohort vs. Period Life Expectancy

If these life expectancy numbers look a lot higher than what you’re used to seeing in media, there’s a reason for that. These are cohort life expectancies, which have real meaning to individuals who are trying to consider things like retirement planning.

In this post from 2022, I explained:

Period life expectancy is the life expectancy you hear reported each year in the press, that gets released by the CDC in these reports, etc.

It is taking the mortality experience for the whole population during a specific time period, usually a single year (in this case, 2021), and then calculating life expectancy as if the mortality seen by the full population during that year was the one a person would be seeing during a lifetime. No person actually lives through a mortality pattern like this, because we’re not in a “steady state” for mortality.

Period life expectancy is the flip-side of age-adjusted mortality rates.

Cohort life expectancy is the life expectancy based on one’s birth year, which is the relevant life expectancy for things such as retirement planning. As an actuary, I’m looking at this measure for pensions and annuities. Well, no, I’m not.

I’m actually looking at the full distribution of possibilities, not the weighted average.

Yeah, I don’t care about life expectancy. I want to look at the whole distribution.

Distribution at death, different birth years

So here are a few different birth years: 1900, 1920, 1940, and 1960 — these are normalized distributions, with 1900 and 1920 being almost entirely actual experience, 1940 only partly projected, and 1960 still mostly alive.

Two pandemics are showing up clearly in these graphs: the spike at age 18 for cohort 1900 is the Spanish flu pandemic.

There are two spikes at older ages, which represent the COVID pandemic: one around age 61 for cohort 1960, and one for ages 80-82 for cohort 1940.

These are normalized curves, so as infant mortality comes down, the curves go up in magnitude at older ages.

Why do we care?

Okay, so what’s up with all these actuarial exercises?

Well, first, to get your attention with the “living to 100” hook — we really do expect larger percentages of people to be living to higher ages. That has repercussions in terms of systems like Social Security and Medicare.

Second, life expectancy may be increasing with this, but predicting farther than a decade or two is pretty foolish. It’s fun to project a century, but come on, man. I can consider all sorts of possibilities with both increased longevity and reduced lifetimes.

Third, the full distribution of death ages can be important to look at - not just single points, like survival to 100 years old or life expectancy. Those spikes showing the pandemic are important, as well as those curves with peaks of modal age at age increasing (meaning, age you’re most likely to die at — which tends to be higher than life expectancy).

And all of these have nothing to do with calendar year statistics, which is what you hear in the media.