U.S. Motor Vehicle Accident Deaths: Seasonal Patterns and June 2023 Update

Top month so far has been October 2021

Hello, new readers! If you haven’t seen this, check out an orientation to this substack. That will get you familiar with the common topics here — including DEATH.

There was an update today to CDC WONDER, the main database for death statistics that I use, so I thought I’d take advantage by making a few graphs.

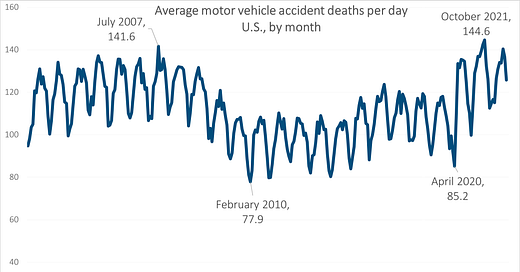

Seasonality of Motor Vehicle Accident Deaths

Most people are used to the seasonality of deaths, as old people tend to die in the winter from pneumonia and heart disease. Other causes of death don’t have a seasonality to them, such as cancer.

There is a seasonality to motor vehicle accident deaths.

As when I first wrote about motor vehicle accident deaths, there are peak times for them, and they tend to be around holidays. Summer holidays. And yes, drunk driving is heavily involved.

The lowest point every year is usually January or February. As I’ve normalized for month length (and yes, I took into account leap years, thanks for asking — you can check by downloading my spreadsheet at the bottom of the post), it’s not because February is the shortest month.

It’s because it’s difficult to die in a motor vehicle accident if you’re not driving anywhere. If you’re snowed in… you’re not driving. If you’re not going on vacation, you’re not driving.

Within one year, there is a lot of variability. To measure this, I take the difference between the maximum and the minimum and compare it as a percentage of the average over the year. Over the period we’re looking at, this variability ranges from 20% - 30%.

Highs and Lows

I picked out four points on that graph to highlight local lows and highs.

The low for the period occurred in February 2010, when there was only an average of 77.9 motor vehicle accident deaths per day.

Before that, the local high had been in July 2007, at a high of 141.6 deaths/day. The most recent high occurred in October 2022, at 144.6 deaths/day. Interesting it took 15 years to get back to that level… and that’s not a good thing.

The fall in deaths from 2007 to 2010 was in line with a long-standing pattern that actuaries have seen: in general, motor vehicle accident deaths have increased with increasing economic activity and decreased during recessions.

You can see notable decreases in motor vehicle accident death rates during recessions — the one in the early 1970s was the oil embargo, so that was particularly hard-hitting in terms of the number of miles people were driving. Also, people weren’t quite driving as fast.

But you can see that in many periods of economic growth, motor vehicle accident death rates climbed, and then dropped during recessions… except for short-lived ones.

To be sure, during the 1990s and 2000s, rates went sort of sideways. Similarly, the 2010s saw rates stay pretty low. I’m not showing you what happened with rates per millions of miles driven — they really did improve. Vehicles were getting safer, with airbags as well as other safety features.

But you see that anomaly during the pandemic - in 2020, motor vehicle accidents did jump up.

Focusing on the pandemic period

Let’s just focus on 2018-2022 (I have to stop at November 2022, as the current data update gets me only the first week of December motor vehicle accident deaths. External deaths — homicides, suicides, and accidental deaths — are not made available in the statistics for 6 months, due to investigative reasons.)

I picked out 4 different points this time — two local high points for 2018 and 2019, both of which were in September. In general, in most years, the high point for motor vehicle accident deaths is sometime in the 3-month period of August - October. September is a very common month, though, due to Labor Day.

Then there is the local low point of April 2020, when many people were locked down, and not driving anywhere.

Then I picked out January 2022 — it was a low point for 2022, and January tends to be a low point for most years.

But I picked it out specifically so you could compare it against the rates in 2018 and 2019. That low in 2022 is only a few percentage points below the high from the pre-pandemic rates.

If you were wondering why your auto insurance rates had gotten so high… well, other things are involved as well. Inflation of various sorts, non-fatal accidents, and theft — these add to insurance costs, too.

But death is a pretty serious business as well.

Dear Mary Pat,

You've pointed out several times that one of the biggest stories in mortality - and especially for children - is the dramatic decline in motor vehicle deaths, over the last 50 years but very dramatically the last ~25.

Yet I doubt very many Americans are aware of this. In the popular press, this important fact seems to be like the story of the three blind men and the elephant, where people confidently describe the elephant based on feeling a small part of it.

(Maybe a better analogy is a distant black hole, or exoplanet, which has to be discovered by watching how things around it react.)

You wrote about how "guns" were breathlessly reported to now be the #1 cause of death for [a stretched definition of] children. Even with shifting the age of "children", they only got to claim this because of the very good and huge decline in auto accidents.

I ran into it again this week, where a writer, who is very insightful about the software industry, repeated the conventional wisdom that Volvo motors was punished in the American market because "Americans (besides a niche market of very smart ppl like the author) just don't care about safety."

A different framing: Volvo was an industry leader, and used their well-deserved reputation for safe vehicles to sell their more expensive cars at a premium. But ALL vehicles sold in the US have become much safer, reducing Volvo's competitive advantage.

The author laments that Volvo was aquired by Ford/Jaguar group, and that their engineering will be sacrificed to market demands. Quote:

".... If Geely declines to continue Volvo's commitment to structural safety, it may not be possible to buy a modern car that's designed to be safe."

-- (link below)

Of course, paying a premium for a car that will still protect you in a few very very rare crash scenarios is something most people would see as a kind of "luxury." What he is also saying is that driving a Volvo signaled that you were smart and likely to get rich, wheras now it just says rich.

(Maybe he has a red 1998 Volvo wagon with expired MA tags, 183,000 miles and a ski rack up on Craigslist and getting no intetest.)

You are just one (implacably logical) woman, how to beat back the tide of base rate fallacies and "Plato's Cave" journalism? I don't have an answer, but you give me hope.

B

Volvo comments are about halfway through. You would never guess this was written by a software engineer...LOL

https://danluu.com/nothing-works/