Taking the Long View: Good Mortality News in Child Mortality

Just reminding you of child mortality improving, and still improving

I am doing something a little different, because I will be giving a big dose of bad mortality news over the next few weeks, as I unpack my updates including 2022 data. I gave a little taste in my last post when I showed an increasing kidney disease death rate from 2019 to 2022.

However, I want to step way back, and focus on a particular area of mortality that, thankfully, really didn’t increase much during the pandemic, and has had a fabulous long-term trend: child mortality.

Child Mortality: Death Rate Before Age 5

First, let us define child mortality for this post, because this is going to differ from many of my other child mortality posts, where I look at ages 1 - 17.

The reason this definition differs is that this is looked at over long periods of history — stretching back centuries. I last wrote about this in 2016, so time for an update, eh?

And yes, I’m giving you some childhood pics of myself, as I was a very happy kid (and baby). I’m alive! Why shouldn’t I be joyful? (It can’t all be mortality graphs.)

The data come from Gapminder, free data, CC-BY, and all that jazz. I accessed the data 21 March 2023, and the data documentation was here as of that date: https://www.gapminder.org/data/documentation/gd005/ - the data are historical up to 2016, it is fairly clear, with some interpolations and estimates going back to 1799.

I’m using the United States and the United Kingdom for my comparisons for reasons that will be clear fairly soon. The U.S. numbers don’t really

I will be quoting mortality rates in terms of percentages, instead of rates per thousand. I will stop at 2016, as past that date, I know the numbers are model projections. (I will use real United States numbers below.)

Here is the graph:

Pre-1880, the data for the U.S. are clearly imposed by a model limit. I am suspicious of the pre-1900 data — it’s really too smooth. You can see the state of the UK data for the 19th century, which shows the noisiness I would expect from “real” data of that period, and even into the first half of the 20th century. The UK’s data is kind of “squishy” pre-1840, but looks like there is a believable, non-model-driven trajectory afterward.

While it may look like the data are model fits post-World War II, these are based on real data. Mortality changes have been fairly small for young children annually, even during the pandemic.

But that’s enough discussion of data quality.

In the 20th century, except for one very clear outlier, both the UK and the U.S. show a similar trajectory in child mortality. The clear outlier is the result of the Spanish flu, unsurprisingly.

But let us think through the rapidity of the improvement of childhood mortality — and that it continues to improve! Even though there is not so much room to improve - the rate for 2016 was 0.4% for the UK and 0.7% for the U.S., and that is including the fact that most of that mortality occurs during the first day of life now.

Still, I want you to consider that even at the beginning of the 20th century, over a fifth of children didn’t make it to age 5 in both the U.S. and the UK.

But by the end of World War II, fewer than one in twenty children died before the age of 5. That is such a great improvement!

Obviously, advancements in public health helped, but many of these occurred before many of the vaccines and antibiotics that we know and use now.

Those helped post-WWII, where that sub-5% child mortality rate has been pushed to below 1%, and is continuing to be pushed even lower.

Dickens on Child Mortality

I’ve talked about Death in Dickens in the STUMP podcast:

And while Dickens killed off far more adults in his novels, he’s most known for the child deaths in his books.

Unsurprisingly, child death touched his own life directly in his family, but also he was concerned about the very common deaths of urban poor children, who were often malnourished, abused, and ill.

From Pediatric Annals, March 2019, 48(3):e97-e97, Reducing Mortality Rates in Children Younger than Age 5 Years Around the World: Charles Dickens' Perspective

After reading the article “Drooping Buds,” which was written in 1852, I was disappointed to learn about the high incidence of infant and childhood mortality rates in London during that time.

Of this great city of London-which, until a few weeks ago, contained no hospital

wherein to treat and study the diseases of children-more than a third of the whole population perishes in infancy and childhood. Twenty four in a hundred die, during the first two years of life; and during the next eight years, eleven die out of the remaining seventy-six.

You can see the full piece here, via a site called the Circumlocution Office, and listen to an audio version here, via the Charles Dickens Museum.

So Dickens was estimating about 1/3 as childhood mortality at that time. He was advocating for building hospitals focusing solely on children, and even featured such a hospital in his last full novel, Our Mutual Friend.

John Graunt, who made estimates in about 1660, as one of the first British life actuaries, also came up with a childhood mortality estimate near 1/3.

(To interpret - this has a probability of 36% of dying before age 6, instead of age 5. Close enough.)

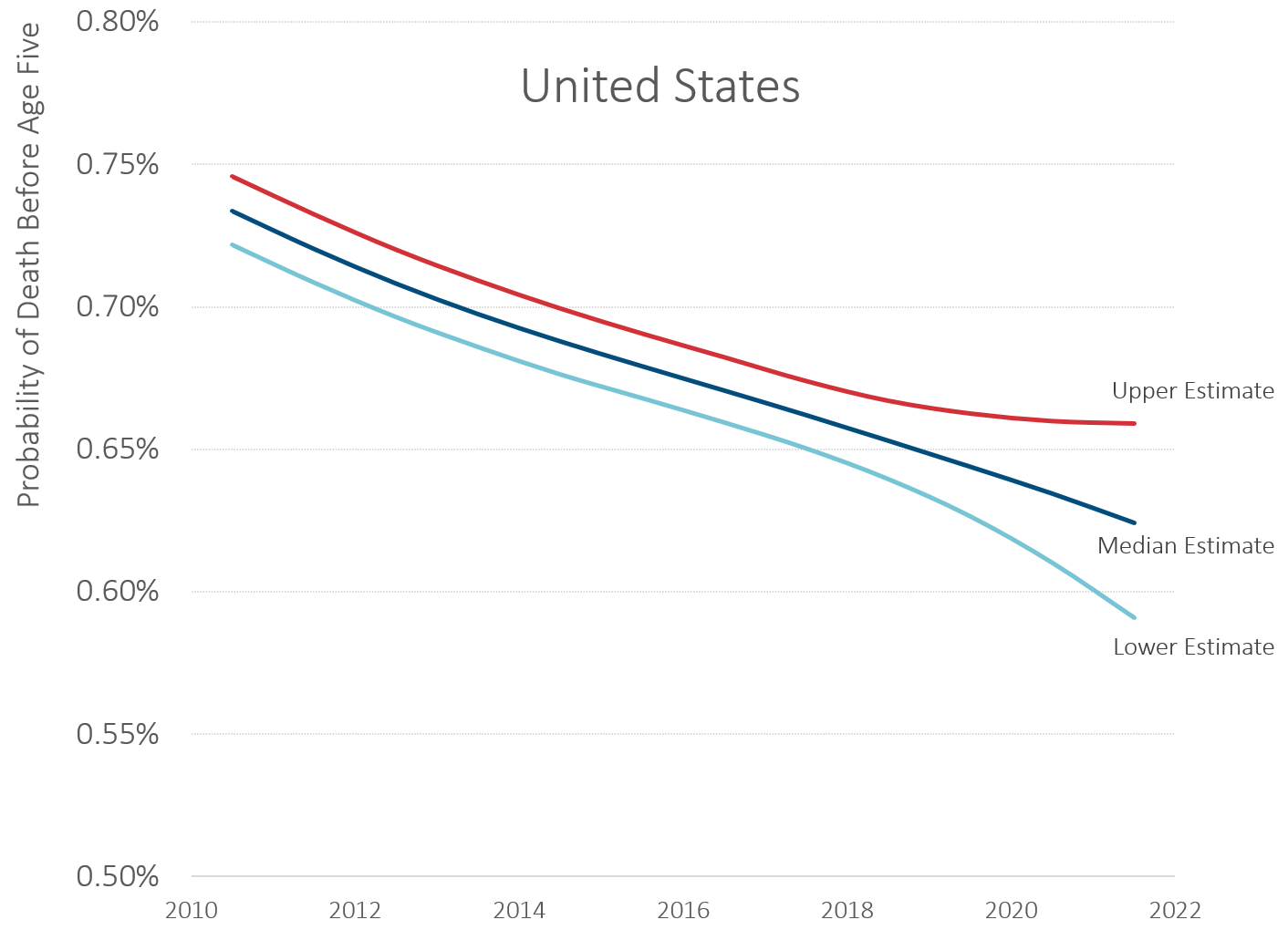

Child Mortality in the U.S. During the Pandemic

These estimates are via UNICEF, which provides a range of estimates:

So yeah, the upper estimate bends a little upward due to the pandemic. Maybe.

But not much.

(This is not just a matter of taking one-year death rates, by the way, but does involve some modeling.)

Speaking of models:

Part of the reason I’m posting this is that I want to remind people of the longer-term view.

It can be quite the grind if you’re always looking at the bad mortality news, because, let’s face it, that’s all you’re going to be hearing about in the news… and that’s what I’m going to be mainly talking about tomorrow to the Iowa Actuaries Club.

Improvement can come back again — remember that nasty blip around the Spanish flu mortality? It had a huge effect on U.S. mortality across multiple demographics, but mortality continued to improve after it had moved through.

So sometimes step back and look at the larger context. It can be a mortality downturn is long-lasting (and there have been historical periods where that has been guessed at, such as during times of war and/or climate stress), or it may be relatively short. It’s a good idea to look for multiple possibilities.

And even if the happy stuff is only for a small bit, such as for child mortality only, that still seems like something important to note.

UPDATE — Spreadsheet: