Sunday at Sea: the Vasa, the Far Side of the World, and Alexander in a Bathysphere

A medley of marine adventures

For now, I will leave the latest oceanic disaster story to others. (For now).

That said, I’ve always had a fascination with the world of the deep more than outer space, especially when my Dad talked to me about the concept of underwater farms and colonies… and then we went to EPCOT in 1984, and there was one bit of underwater living spaces! On the ocean floor! Wow!

So here are three sea-related items I’ve been thinking about lately, starting with a very real disaster… but not a recent one.

The Swedish Ship Disaster: Vasa

I was reminded about this particular disaster due to my recent visit to the Museum of Failure.

This failure was ultimately the fault of Sweden’s King Gustavus Adolphus, who wanted to show off his kingdom’s might and wealth in the early 17th century. It not only carried way too many guns, but it also had a bunch of pointless (and heavy) decorations.

Smithsonian Magazine: The Bizarre Story of ‘Vasa,’ the Ship That Keeps On Giving

The management world has a name for human problems of communication and management that cause projects to founder and fail–Vasa syndrome. The events of August 10, 1628 had such a big impact that the sinking is a case study business experts still read about.

“An organization’s goals must be appropriately matched to its capabilities,” write Kessler, Bierly and Gopalakrishnan. In the case of the Vasa, “there was an overemphasis on the ship’s elegance and firepower and reduced importance on its seaworthiness and stability,” they write, “which are more critical issues.” Although it was originally designed to carry 36 guns, it was sent to sea with twice that number. At the same time, the beautiful ornamentation contributed to its heaviness and instability, they write. These and a host of other factors contributed to Vasa’s sinking and provide a cautionary tale for those designing and testing new technologies.

I didn’t get into the detail of the sinking, because this wasn’t even a Titanic situation: it didn’t even make it out of the harbor. And it was a calm day.

You can read various accounts of the explanation of the situation, but this one looks simple enough:

After about 20 minutes, in the middle of the harbor, a gust of wind hit it broadside and it heeled (tilted). Heeling was, and is, normal for a sailboat, but this one had some serious faults in the design:

1. It was not well-proportioned: 69 meters long, originally 52 meters high, 11.8 meters wide. That made it too narrow and too tall. This could have been compensated for with a deep enough keel with enough weight on it, but this ship’s center of gravity was too high. The carvings decorating the ship added weight high up, as did all of the cannons on its gundecks.

2. At the same time, the lower gundeck’s cannon ports were just a meter and a half above the water line.

The combination of these two faults meant that the boat, when the gust hit it, leaned steeply, and water gushed into the hold through the bottom row of cannon ports. The boat filled quickly with water and sank, settling on the seabed with about 20 meters of masts still showing above the water.

Most of the people on the ship were able to be saved or get to shore, but some dozens did drown.

In the investigation afterward, blame was dodged by many, and ultimately they settled on the original designer, who had conveniently died the previous year.

But there’s an interesting “success” part to this story, which is the museum made centuries later.

Today she is majestically displayed at the Vasa museum that was built around her. Beyond her history, the techniques that have been implemented and researched to conserve her are fascinating. As ironic as it is, the Swedes succeeded in turning a terrible failure into the most visited museum of the country and a national pride.

The Far Side of the World

That title may sound familiar to you, in that it is the subtitle of the movie Master and Commander from 2003. Back when Russell Crowe was still hot.

I’ve been going through Patrick O’Brian’s series on the Jack Aubrey/Stephen Maturin duo set during the Napoleonic Wars, and I have finally gotten to the novel titled The Far Side of the World — which is the 10th in the series. Master and Commander is the first book in the series.

I’ve been listening to the audiobook versions of these books, which are read by Patrick Tull, who is great at getting all the nautical terms correctly pronounced.

After having heard a different audiobook heavy on the nautical terms, but with all the terms mispronounced, I made this video with my kids (some years ago):

Yeah, I was having some fun.

Before I leave this series, which not only has adventure reaching across the world, also has spycraft, romance, mystery, but also natural science!

In particular, in one of the novels, Stephen Maturin receives a diving bell, based on a design by Edmond Halley (yes, the comet guy… and yes, the guy who did the mortality tables.)

In 1691, Halley built a diving bell, a device in which the atmosphere was replenished by way of weighted barrels of air sent down from the surface.[31] In a demonstration, Halley and five companions dived to 60 feet (18 m) in the River Thames, and remained there for over an hour and a half. Halley's bell was of little use for practical salvage work, as it was very heavy, but he made improvements to it over time, later extending his underwater exposure time to over 4 hours.[32] Halley suffered one of the earliest recorded cases of middle ear barotrauma.[31]

Maturin uses the bell to make underwater observations on that particular trip, and also to do something plot-important (which I will not divulge….), but that leads me to my next item.

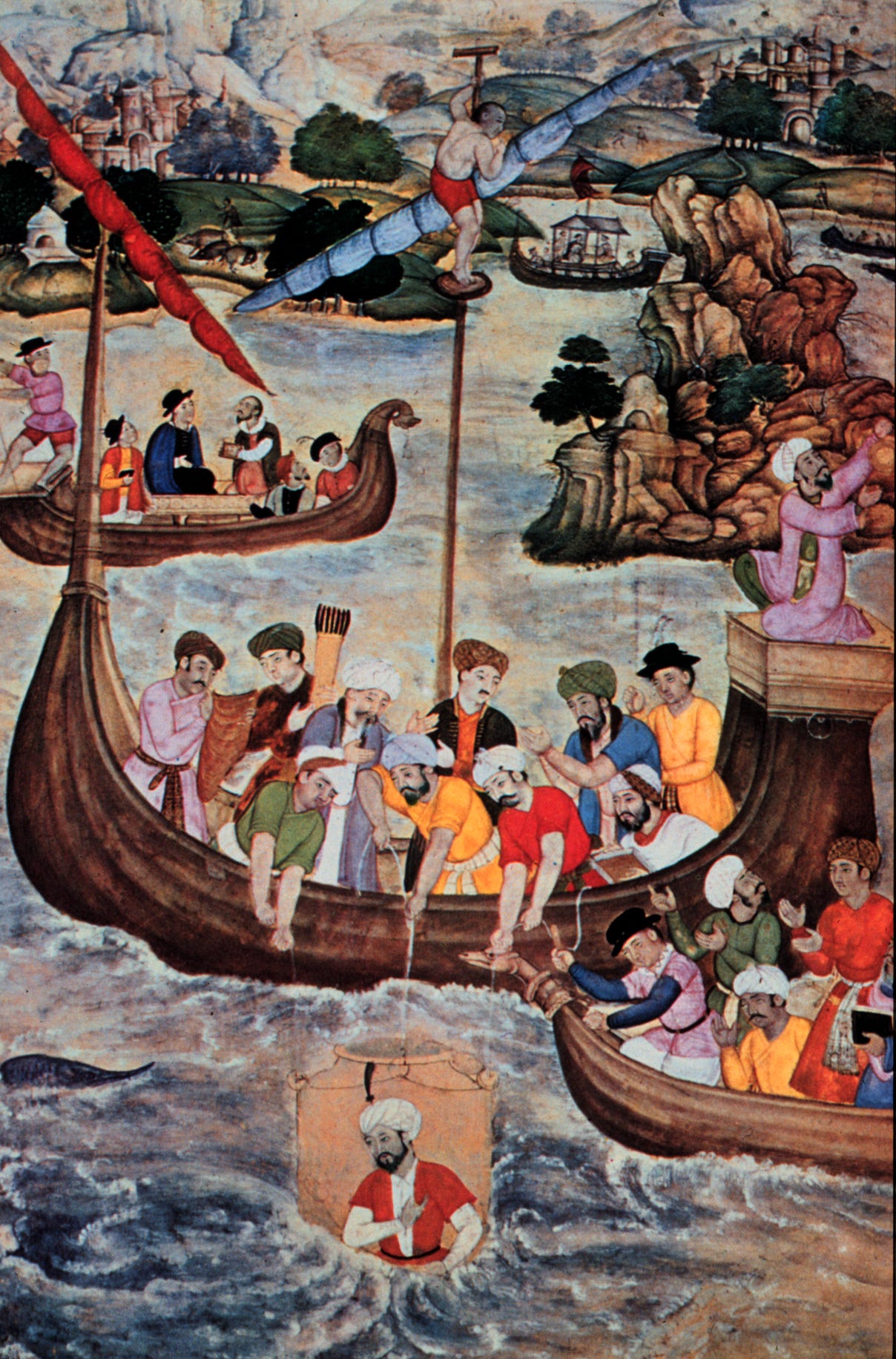

Alexander the Great and the Bathysphere

This one may be as fictional as the prior, but it makes for fun art.

The general story/legend is that Alex the Great used some sort of diving bell or bathysphere to do various things: observe marine life (could be — Aristotle was his teacher, after all), scout underwater defenses of cities, make a getaway. There are some definitely fictional stories involving a dog, a cat, and a rooster and an unfaithful lover… and it doesn’t really work, science-wise (yeah, I don’t see a dog working as an oxygen tank).

The stories and art that we have come from medieval European as well as Islamic sources - that is, over 1,500 years after Alexander the Great died. So…. yeah.

From the story of the lover & the animals:

Just looks like a bad idea in general.

Dear Mary Pat,

If you are interested in the technical aspects of ships in tbe Age of Sail, I have found an amazing resource, hosted by the (US) Historic Naval Ships Assn.

Oh crap. Just like that, the site has gone dark. The "Text-book of Seamanship" had been archived here:

https://archive.hnsa.org/doc/luce/index.htm

I had been meaning to donate, now it seems I am too late.