Suicide: Trends, 1968-2020, and Provisional Counts Through June 2021

Not all subpopulations have trends moving the same way

As per my promise, I will be walking through major “external” causes of death in this and upcoming blog posts, trying to get at drivers of excess mortality beyond just COVID and other natural causes:

1. Suicide

2. Homicide

3. Drug overdoses

4. Motor vehicle accidents

These 4 items have different trajectories and effects through the pandemic, and had different trajectories before the pandemic. In some cases, the trend was bad before the pandemic, and was made worse. In some cases, the trajectory is just continuing as it was before.

In this post, we will see what the trend has been for suicide before the pandemic, how it’s changed during the pandemic, and what we’re seeing through June 2021.

This post is too long for email, so if you got this via email, you’ll need to click on the title to get to the full post, which has links to the underlying spreadsheets at the end. Sorry, just too many graphs, I guess.

High-level trend: down and then up

First, let’s look at the highest level of trend, 1968-2020:

The rates we will be looking at will be back at the standard units, which is per 100,000 people per year. The crude death rate is simply the number of deaths divided by the population and the age-adjusted death rate is using a standardized age distribution to capture any age-related aspects (which, we will see, aren’t as strong for suicide as it is for natural causes of death.)

In general, we’ll be looking at age-adjusted death rates for groupings (and if it’s an age group, we just use the regular rate). We can see that there had been a steady trend of increasing death rates by suicide since 2000, peaking in 2018, and came down in 2019 and 2020.

Now, when I had been looking at deaths by suicide in death counts during 2020 through 2021, I noticed it didn’t look like they had been going up. Indeed, this is showing the rates are going down.

That said, just because for the entire population you see a decrease does not mean that’s what’s happening for subpopulations.

Sex and racial gap in suicide

If I pull the data back to 1968, the only “stable” racial categorizations are white and black. So let’s look at white/black and male/female breakouts of suicide rates:

Now that we’re starting to break the population into subpopulations, we see large gulfs in rates. We also see large differences in trends.

White males have the highest rates in this particular grouping (just wait, they’re actually not the worst. Just for these 4.) It looks like their peak rate in 2018 and then decrease may be driving the suicide rate result for the overall population for a variety of reasons. Remember that these four groups are not of equal size. Of these four, white women will be the largest (mainly because they live longer than white men, and African-Americans are about 13% of the U.S. population.)

I see that in recent years, suicide rates for black men have been increasing, and did not decrease in 2020.

Black women have the lowest rates in this group.

If I want a more diverse categorization, I have to restrict myself to the 1999-2020 database:

I told you there was a group with a worse suicide rate than white men. Now Native Americans are a very small percentage of the U.S. population, so that hideous trend has little effect on the overall population trend we see. But lord, that’s an awful trend, for both Native men and women. In general, for all the groups, there has been a general increasing trend in suicide rates.

A final snapshot, with 2019 and 2020 rates:

Some went up; some went down. I don’t know how significant these movements are. As we can see, there was already a general increasing trend for all these groups before 2020.

Age groups and suicide

This is a pretty important slice-and-dice, because of how suicide prevention and resources are often deployed in the U.S.

I’m going to lead with the snapshot graph here first, because it’s going to be something you may not expect:

Here, I’m showing the 2019 and 2020 death rates by suicide for specific age groups. Note that there isn’t a lot of difference between the death rates for adults, except it’s a little lower for the kids.

It looks like the rates increased somewhat for all groups under age 35 between 2019 and 2020, plus increased for those over age 85. For the other ages it decreased. Again, we can see the difference of a rate decreasing for the overall population, but moving in different directions for different subpopulations. This happens all the time in life.

So, given that suicide death rates are pretty much in the same range among all adults, is it unreasonable to focus so much suicide prevention resources on teens? On college students? I could spend time on going into how it’s easier to organize through schools, and I can also spend time on how it’s so many more years lost when you die young, from any cause.

But here’s a much bigger explanation:

It really focuses the mind when it’s 20% of the deaths for the group. That’s a lot. As we look to older and older people, there are so many more things killing them: cancer and heart disease, liver disease and kidney disease, diabetes, Alzheimers, etc. The focus gets diffuse. The suicide rate is just as high as it ever was, but it doesn’t even rank in the top ten causes of death for the oldest people — natural causes really increase in their force of mortality.

So let’s break out the age group trajectories over time:

I broke these into three graphs because I saw these as school age, working age, and retirement age… and just in my unscientific eyeballing, it seemed that the lines in each separate grouping had similar trajectories, though not exactly the same levels. Not quite sure why we’re seeing these shapes. Really interesting.

Suicide death numbers, 2019-June 2021, by quarter

I decided to group suicide numbers by quarter because quarters are roughly equal in length (3 months each), and have sufficient numbers of deaths to have some stable statistical analysis. Not that I’m doing actual statistical analysis at this point.

I’m doing what was called the interocular trauma test by some statistical smartass once upon a time (“Does it hit you between the eyes?”)

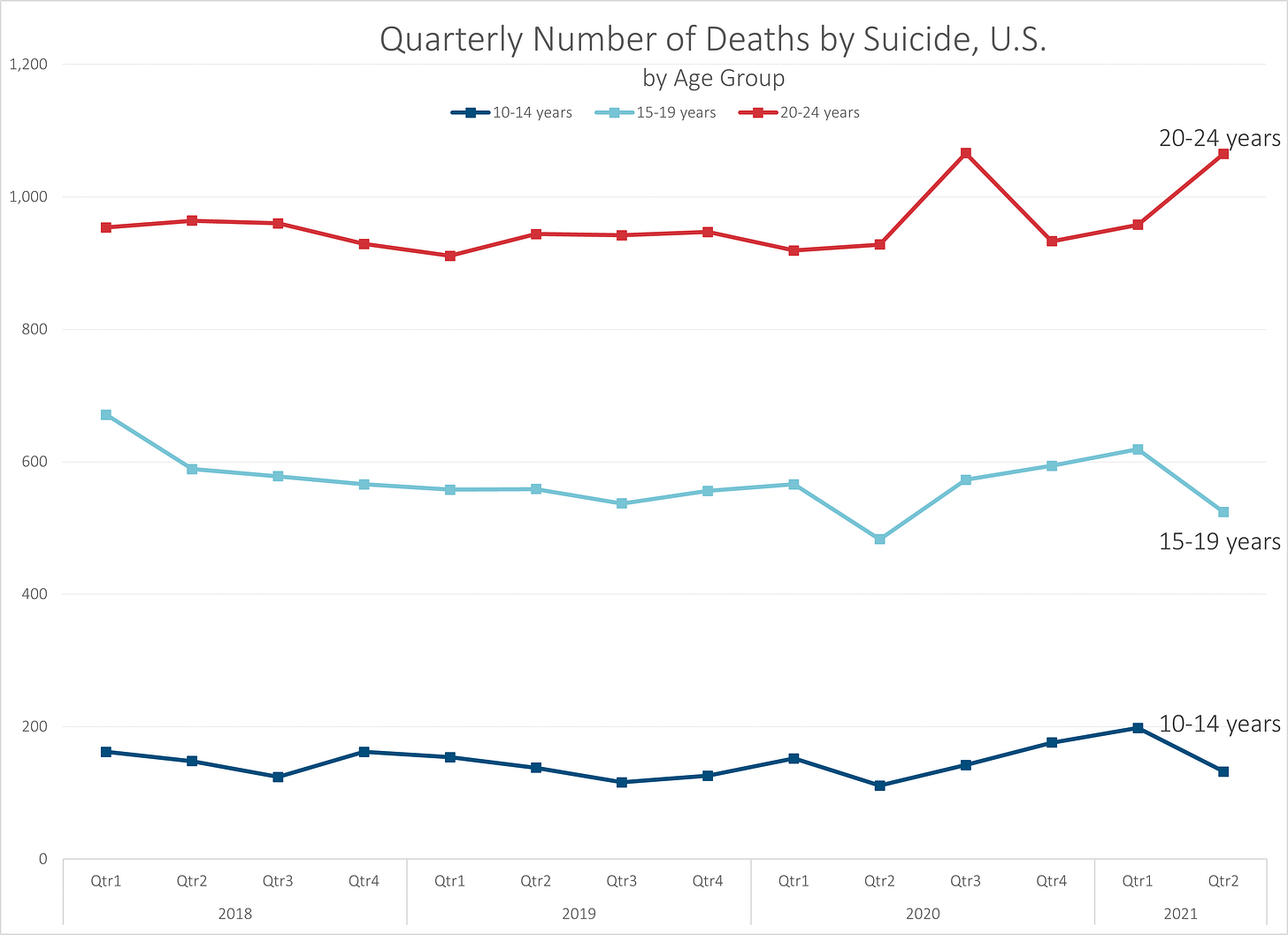

To make it easier to look at, I decided to use the 5-year age groups, and do them in triplets (or a quadruplet, if I needed that). Let us start at the youngest ages and work our way up:

Starting at the youngest ages, we know we have some relatively low numbers to begin with, which should caution us: remember, this is for the whole country, and if you’re considering only a few hundred people over 3 months for the whole country of over 330 million people total, yeah, we want to be careful about noise moving trends around.

That said, for the under 20-year olds, we see a dip in 2020Q2, which makes sense … if the kids are forced to stay home, and their parents are forces to stay home too, it’s not so much about desire so much as ability to execute. If you never get an opportunity, there ya go. However, what is up with that large spike in 2020Q3 for 20-24-year-olds? I don’t know. Similarly, why are numbers for 2021Q2 (remember: Q2 is April, May, June) down for age 10-19, and up for 20-24? I don’t know.

We have those weird Q3 spikes for age 35-39 years, and I can’t tell you anything — those spikes are in 2018 and 2019 as well, not just 2020. What is this summer suicide thing?

Here we see a clear trend: down. It was trending down somewhat before the pandemic, too.

Again, trending down.

This looks sideways to me… no clear trend in this data.

Baseline results: maybe some increases for teens and younger adults

Just doing a quick calculation from rates, going from 2019 to 2020 rates, here are the increases in death rates by suicide:

Age 10-14: 8%

Age 15-19: 1%

Age 20-24: 3%

Age 25-34: 5%

Also, an increase of 4% for age 85+.

Now, these are substantial increases in death rates, and we will see if they continued into 2021. I did not calculate a half-year rate from the 2021 counts, because I didn’t want to project the half-year results to a full year.

That said, you need to look at the trends from before the pandemic before you start blaming the pandemic for these changes. Because, as you can see, suicide death rates already had a bad trend before 2020. It’s not clear to me that the pandemic accelerated increases that already existed, unlike with drug overdoses, where there clearly was a change in rate, or homicides, where I think there may have been a phase shift.

In any case, getting the statistics straight in your head can help you navigate what is driving non-COVID mortality, especially for younger people. There is a component of suicide involved, but it looks like this is a continuation of an extremely nasty situation that existed before 2020.

Prior posts on suicide:

Nov 2021: Movember Fundraising: Men and Suicide

Dec 2020: COVID News Round-up: Suicides, Increasing Deaths, Duty to Die, and Dolly Parton

July 2017: Mortality Monday: Suicide — Rates

April 2021: Mortality with Meep: Top Causes of Death in the United States in 2020