State Bankruptcy and Bailout Reactions: Would Pensions Really Have to be Cut in Bankruptcy?

It depends on what one means by "have to" and "bankruptcy"

I get email (marypat.campbell@gmail.com) – and often, it gives me a chance to revisit and sharpen an argument.

Excerpts from the email sent to me:

“If there is a court-supervised process, as with Detroit’s massive municipal bankruptcy that means all creditors will have to see cuts. Including pensioners.”

If I understand correctly, the precedent set by Vallejo, Stockton, San Bernardino, Detroit and as proposed in Puerto Rico is that pensioners stay >=95% whole and bond holders absorb all of the losses. In theory Chapter 9 should allow pensions to be cut, but the one and only submitted plan comes from the municipality. And in each of those cases, they chose NOT to materially cut the pensions. The Chapter 9 BK judge apparently must binarily accept or reject the plan in its entirety. He/she does not have the ability to make line item adjustments

David Skeel is on the PROMESA oversight board and they have gone as far as declaring some Puerto Rico GO bonds unconstitutionally issued and therefore worth literally zero cents on the dollar. So far the board has not made or proposed any substantial changes to pensions.

First, the writer is quoting something I wrote in this post, and here is the context:

And that makes a state bankruptcy process meaningless for the states I named above [Illinois, New Jersey, Kentucky, Connecticut]. They don’t want to do it this way, because it means far more than defaulting on bondholders [which they can get away with…… once.]

If there is a court-supervised process, as with Detroit’s massive municipal bankruptcy, that means all creditors will have to see cuts.

Including pensioners.

The email writer is correct that municipal bankruptcy does not mean that public pensions have to be cut at all. Indeed, before the Detroit bankruptcy, we didn’t have public pension cuts in bankruptcy, and many groups were trying to prevent that from happening as part of the official workout project.

I am going to explain why for those particular states, under any reasonable real bankruptcy process, the pensions would have to be cut.

The short reason is: even if these states defaulted on all their bondholders, they still wouldn’t be able to support their pension systems.

But let me address my incorrect statement about municipal bankruptcy.

My email reply

[I’m not putting this in quotes — as it’s a copy/paste of what I wrote]

Good point — remember, I am not a lawyer of any kind, never mind a municipal bankruptcy lawyer.

So there are a couple differences between Detroit & the California bankruptcies. If I remember correctly, all the pensions for Vallejo, Stockton, and San Bernardino were under one of the state funds — Calpers or Calstrs. I could be wrong about that. But it limited the legal options to do any pension-cutting, under those programs. The Detroit pensions that were cut were all city-level funds.

Calpers definitely put in its oar with respect to pensions being able to be cut in the bankruptcy proceedings, and was successful in all the California cases [they were considered a creditor]; it filed an amicus brief in the Detroit bankruptcy, and had no effect.

I would have to look through my notes on the Detroit bankruptcy [which starts here: http://www.actuarialoutpost.com/actuarial_discussion_forum/showthread.php?t=263796 and goes on for almost 650 posts] — but if I remember correctly, the judge either accepts the terms or says “No, do better”. And the “do better” is not necessarily based on fairness to creditors, but on whether the entity would actually be solvent on a long-term basis. I was (and am) skeptical that the pension cuts were enough for Detroit [especially since the teachers plan wasn’t cut], but in order to be sustainable, they had to cut the pensions.

I guess my real point is that many of these systems are so bankrupt (Illinois and New Jersey specifically) that they could 100% default on their bonds… and still be insolvent due to the pensions. Pensions would have to be cut for any believably sustainable workout.

Thanks for bringing this up, because I can now do a followup post once I find my notes on all these bankruptcies. ;) You may see some familiar words this coming week…..

Some pre-COVID numbers on state-level debt

That was my email, so I want to actually look up what I asserted. First, the debt level of states, and what portion of that debt is unfunded retiree benefits [not only pensions, but also retiree health care].

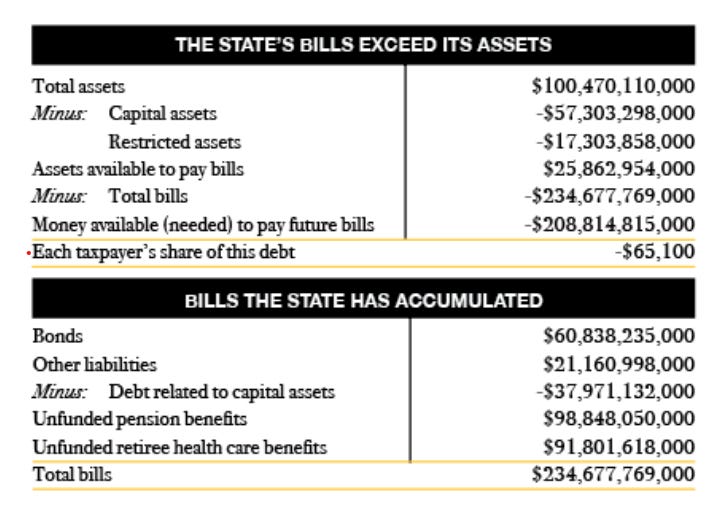

I am going to use Truth in Accounting’s numbers for states, so that we can look at the source of each state’s debt.

I’m going to pick on Illinios and New Jersey, specifically, because of course I am. Also, they’re at the very bottom of TIA’s list. And they really are the worst for state-level debt.

Only $41.7 billion out of Illinois’s $254.5 billion total debt are bonds. That’s only 16% of the total debt.

And that’s just using the official estimates for the pension and retiree healthcare liabilities, which may be underestimating their ultimate cost.

Using those numbers, the unfunded retiree benefits (pension and healthcare) amount to 79% of Illinois’s debt. When the crunch comes, trying to default on everything else will likely not work.

As with Illinois, retiree benefits represent 81% of New Jersey’s debt.

Let me contrast this to New York, of which retiree benefits debt is only 44% of its total debt.

Even for Connecticut, retiree benefits debt is “only” 67% of its total debt. [Connecticut is its own mess.]

In any state bankruptcy proceeding, there would be a question as to whether an Illinois or New Jersey rehabilitation workout not including pensions would actually be sustainable. Especially since retiree benefits make up four-fifths of their debt load.

[AND THAT’S BEING OPTIMISTIC]

Let’s look at three relatively recent large municipal bankruptcies: two of which did not include pension cuts, and one which did. Detroit, Stockton, and San Bernardino.

History of Recent Muni Bankruptcies: Detroit and pension cuts

I had a thread on the Detroit bankruptcy at the Actuarial Outpost, because it was so huge, but I’ve got several other related threads. In specific: Muni Watch, because that’s where I followed Stockton and San Bernardino bankruptcies.

Let me dig through those piles, shall I?

June 2013 by Felix Salmon: Detroit takes aim at its pensioners

As far as Detroit’s balance sheet is concerned, there is $9 billion of debt, excluding pension liabilities, and also excluding healthcare and life insurance obligations which are calculated at roughly $6 billion. Debt service in 2013 is projected at more than $240 million, or about 22% of total revenues. Worryingly, under the section of the proposal headed “Realization of Value of Assets”, one finds the priceless collection owned by the Detroit Institute of Arts:

Well, owned by Detroit, and it definitely had a price. It formed the core of the “Grand Bargain” used to get all the other players in line.

In Detroit’s case, note that there was $9 billion in non-benefits-related debt and $6 billion in pension debt. Unlike with Illinois and New Jersey, Detroit’s debt was not primarily pension-related. There are all sorts of issues with what happened with Detroit pensions, but on the whole, they actually tried to fully-fund their pensions.

[unlike Illinois and New Jersey. Ever.]

Even so, there is a huge difference between those two pieces of debt: the $9 billion in bonded debt was a lot easier to determine than the $6 billion in pension debt.

If you issued $9 billion in face value of bonds [or whatever it happened to be] at a particular interest rate, with a certain pattern of coupon + principal payments to be made, one can do a quick present value calculation of that bond. It’s not intended to be tricky.

However, that pension debt is an estimate, trying to value uncertain cash flows both in [contributions and investment return] and out of the fund [the benefit payments]. Given actual public pension valuation practice, I am willing to bet the eventual cost of that pension debt would have been more than $6 billion.

To get the Detroit bankruptcy completed, it required the Michigan governor, a Republican, to bring in an emergency manager to force the filing for Chapter 9 bankruptcy. There were lawsuits galore just to prevent the bankruptcy filing (that obviously didn’t work) and to prevent pensions from being cut while in Chapter 9 (that also didn’t work).

Some of the prior Detroit politicians involved in how Detroit got the way it was (in particular, former mayor Kwame Kilpatrick) were not around to object. Because they were federal prisoners. (I just noticed Kilpatrick and his family asked for early release due to COVID-19 risks – under normal rules, his first available time to be released would be 2037.)

But the point is that it took a bunch of politicians and other people from outside Detroit to force this bankruptcy and all the cuts that got made. The specific political players within Detroit itself had no interest in touching bankruptcy. The option was taken away from them by the state government.

Detroit’s bankruptcy process was completed by the end of 2014.

Nathan Bomey wrote a book about it, and I highly recommend it.

California bankruptcies: Stockton and San Bernardino with no pension cuts

Contrast that to the earlier bankruptcies of Stockton and San Bernardino, both of which were different varieties of messes.

Both Stockton and San Bernardino filed for bankruptcy under their own steam, as it were. Stockton filed in June 2012, and before Detroit’s bankruptcy, had been the largest city so far to file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy. San Bernardino filed either at the end of July 2012 or beginning of August 2012. Stockton didn’t complete the process until February 2015, and San Bernardino took until June 2017.

They filed for bankruptcy before Detroit, and got out after Detroit. San Bernardino’s bankruptcy was the longest in recent experience. As Liz Farmer wrote in 2016:

Four years ago this month, San Bernardino, Calif., filed for Chapter 9 protection. Today, it’s still in Chapter 9 — the longest municipal bankruptcy in recent memory.

Why so long? Many blame it on San Bernardino’s lengthy and convoluted charter, a document that gives so much authority to so many officials that it’s completely ineffective. “It gets everybody in everybody else’s business,” said City Manager Mark Scott. “And it keeps anybody from doing anything.”

As a result, officials have spent the last two years trying to ensure the current charter is not part of the city’s future. A specially appointed committee is proposing to completely overhaul it.

That was for a city, not a state. Consider having to deal with a state constitution as opposed to a city charter.

In any case, pensions were not cut for Stockton and San Bernardino, and the main reason why is that their pensions were run by Calpers and Calstrs. To get out of those pension funds is a poison pill. Calpers, specifically, has been adamant in fighting the legal battles to make sure nobody escapes without severe penalties.

Stockton obligations

From April 2013: Pension issue in Stockton, Calif., bankruptcy

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — On its first official day in bankruptcy, the city of Stockton now must grapple with the hard part of reorganizing its financial affairs — how to share the financial burden equitably among creditors while meeting its massive state pension obligations.

At the conclusion of a three-day trial, a judge on Monday formally granted the city Chapter 9 protection, over the objections of creditors who questioned whether it was fair for the city to fully meet its obligations to the state pension system while other debt holders go partly paid.

…..

Stockton’s biggest creditors insured $165 million in bonds the city issued in 2007 to keep up with CalPERS payments as property taxes plummeted during the recession. Stockton now owes CalPERS about $900 million to cover pension promises — by far the city’s largest financial obligation.

You may wish to read the whole thing. It lays out the arguments being made as to whether the pensions could or should be shorted.

In the Detroit bankruptcy, in which the pension funds were city-level entities and not state-level, the pension benefits were cut, even for current retirees. The hope was, that if the funds recovered, perhaps the benefits could be boosted up again. But it would take recovery of the city and the funds.

Ultimately, Stockton pensions were not cut at all in bankruptcy, nor were San Bernardino’s. Neither city was interested in having to fight Calpers. UPDATE: I was wrong about that. More here: Bankruptcy Followup: On Stockton, Public Pensions, and the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

From October 2014: Judge approves Stockton’s plan to repay creditors, leaving pensions intact

Government pensions in California remain untouchable, at least for now, after a bankruptcy judge approved Stockton’s plan to repay its creditors Thursday without reducing the city’s pension obligations.

In a major victory for CalPERS and public employees, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein approved Stockton’s reorganization plan over the objections of a disgruntled investment firm, Franklin Templeton, which wanted more money at the expense of the city’s pension benefits. “This plan, I’m persuaded, is about the best that can be done,” Klein told a packed courtroom in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Sacramento.

In some notes I made at the time, it sounds like Stockton retirees did lose retiree health insurance, though. San Bernardino decided to try to cut pension costs by contracting out for certain municipal services, so that those folks wouldn’t be city workers and thus not covered by Calpers. (That was part of this plan from 2015, and things may have changed.)

Are Stockton and San Bernardino fiscally healthy now?

So here’s a question: after cutting bondholders to the quick, and not defaulting on Calpers, how have these two towns been doing?

Steve Greenhut in June 2018: Formerly bankrupt Stockton is fiscally healthy again, but offers warning to others

“Unlike most cities, Stockton’s elected officials have only promised the amount of benefits they can afford to pay,” according to a report from Chicago-based Truth In Accounting. “Because of this, Stockton has enough money to pay all of its bills.” The group finds that after bills are paid, the city has an impressive surplus of $3,000 for each taxpayer.

This is noteworthy, but something requiring a more skeptical take. If a city overspends its income for decades and then finds itself unable to pay its bills, it can declare bankruptcy, stiff its creditors, slash health benefits for public employees and impose a new “public safety” sales tax and a library/parks tax on city residents. After starting fresh, so to speak, it can be on the way to fiscal health.

Indeed, the report notes that Stockton is in a far better financial position “since a judge ruled the city was eligible for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection in 2013” as a way to get out from under its “staggering debt burden.” The good news is the city now has plenty of assets to pay its bills and is enjoying the fruits of a recovering economy. The bad news is Stockton still has $390 million in unfunded pension liabilities.

Remember, this is after 8 years of a bull market that Greenhut is mentioning pension debt.

In the end, federal Judge Christopher Klein wrote that “CalPERS has bullied its way about in this case with an iron fist insisting that it and the municipal pensions it services are inviolable. The bully may have an iron fist, but it also turns out to have a glass jaw.” He ruled that pensions could indeed be reduced if a city declares bankruptcy, but nevertheless approved Stockton tax-raising work-out plan that did not reduce pensions because the city showed that it could pay its bills going forward.

Well, that was 2018.

What about now? After a huge drop in tax revenues for all state and local governments?

April 2020: San Bernardino faces $5 million deficit as coronavirus pandemic pares revenue

San Bernardino faces a $5 million deficit this summer as major revenue streams dry up due to the state’s stay-at-home order in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Just two months ago, the city was projected to end fiscal 2019-20 with a slight surplus.

In the time since, elected officials have declared a local emergency and have taken a number of steps to ensure essential services still can be delivered.

…..

“The loss of revenue related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” a staff report reads, “will have a significant impact on the financial health and well being of the City of San Bernardino and its residents.”San Bernardino faced an $11.2 million deficit this time last year, not long after exiting bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy judges really don’t want to be seeing you again soon after the prior workout. It indicates something was deficient in the rehabilitation plan.

[Of course, the pandemic can be argued to be extraordinary circumstances, so… fair enough.]

This is not unique to Stockton (or San Bernardino or Illinois or New Jersey), but pensions and other retiree benefits are often the biggest obligations they have. San Bernardino, by outsourcing various municipal functions, may actually be hit less than Stockton (which doesn’t look like it did the same).

As for Detroit pensions, those for Detroit teachers didn’t get cut, because the school system is totally separate in finances and didn’t officially go bankrupt. There’s a question there how supportable it is.

So what about state bankruptcy?

The whole point of allowing a formal bankruptcy process for states in federal courts:

So things can actually get cleaned up.

If there were a state bankruptcy process, no matter how voluntary it was to file it, there is little reason to believe that the most-indebted states would be able to get a workout plan approved by a federal judge if 80%+ of their debt are pensions that have not been cut at all.

This is what I mean by “pensions would have to be cut in a state bankruptcy”.

The only way the bankruptcy process has legitimacy is that what emerges at the end is actually sustainable. [This is why I keep referring to what’s happening in Puerto Rico as a “fake bankruptcy”; there have been few moves towards a sustainable fiscal situation for the non-sovereign island.]

The types of states so burdened by debt that they need some other body providing oversight for their debt restructuring have very high retiree benefit debt and it is their most significant debt. As we saw above, just using official numbers, it’s about 80% of the debt of both Illinois and New Jersey.

No, not all states have to cut pensions to be able to continue fiscally — but they also don’t have to declare bankruptcy.

So yes, in order for the most indebted states to restructure their debt so that they could support it going forward, they would have to cut already accrued public employee benefits.

Fun with a theoretical situation

In any case, state bankruptcy is not going to be on the table, so all of this is a theoretical exercise.

People like to point to Puerto Rico as a trial run, and the fake bankruptcy there hasn’t fixed much. They haven’t even issued audited financial statements in years. How can one even figure out what’s sustainable going forward without that?

As the email writer noted, no pensions have been cut in Puerto Rico [and their pensions are essentially pay-as-they-go].

Anyone wanting state bankruptcy as a solution need to explain why it would work better for sovereign states when it has not done much for the non-sovereign Puerto Rico.

As it is, the last item I see for Puerto Rico is, in April, the federal judge overseeing the process said Puerto Rico couldn’t send money to municipalities for pensions and other benefits. But that ruling is on hold, as are multiple other lawsuits [and we’re waiting for the ruling in this Supreme Court case].

The Puerto Rico situation is definitely not finalized, and this has been going on for four years already. For all that a plan was submitted in September 2019, all of this is still getting worked out.

You think the San Bernardino bankruptcy took a long time?

You think a state bankruptcy would go any faster?

Time would be better spent building up political will for fiscal sanity in the profligate states by those who have not been run off already.