State Bankruptcy and Bailout Reactions: More Reactions

The ants aren't interested in feeding the grasshopper

Quick reminder for order of events:

In April, a bunch of Illinois Democratic legislators asking for federal money for all sorts of things, including a specific item for their pensions

In reaction, Mitch McConnell said that Congress could make state bankruptcy a thing, how about it?

A bunch of responses ensued, with different takes on whether the feds should bailout states in this year of reduced revenues and whether state bankruptcy should be a thing

Here is my prior compilation of responses:

No Pension Bailout, No State Bankruptcy Contingent (I’m in this group)

Now, I didn’t cover the YES BAILOUT group, because I was, essentially, waiting for the House of Reps to pass the bailout bill. It’s officially called the HEROES Act (and no, I’m not looking up to see what stupid acronym that is), but I call it the MoneyPalooza Monstrosity.

I covered a variety of topics on the bill, but I just want to focus on the state aid provisions and the positioning of the YES BAILOUT! folks.

The thing is, while I did wait a bit to gather up reactions, there have been some I didn’t post yet [because they came after my posts].

No to bailouts under any condition

A couple people from fiscally conservative think tanks, at the Hill: State and local bailouts would reward fiscal wastefulness

Some lawmakers want the federal government to shower state capitols with money, not just to backfill revenue losses, but to cover expenses for problems that existed long before the pandemic began. Pension underfunding is one example. Some states failed to set aside enough money to fund their pension promises; now, they want taxpayers everywhere to subsidize their fiscal follies.

…..

Essentially, taxpayers are paying a lot and are getting little in return. But a bailout would do nothing to fix Connecticut’s unfunded liability problem; rather, it would reward the state’s fiscal profligacy and ensure that the dysfunctional status quo continues for another generation.Contrast these two states with Michigan. The Great Lake State suffered its own one-state recession in the 2000s, which was compounded by the Great Recession. It struggled but worked hard to balance its own budget and enacted prudent fiscal reforms. For example, lawmakers worked to prevent future problems by moving to 401(k)-style retirement benefits and using better assumptions about plans going forward.

This history of hard-won reform is important because a bailout effectively would reward the fiscal mismanagement of officials in states such as Illinois or Connecticut while punishing lawmakers in Michigan for their hard work and restraint. In short, bailouts would discourage sound solutions and real leadership, and encourage more bad choices. Forcing all taxpayers to bail out fiscally irresponsible states and local governments would be a profound injustice to those who have voted for more responsible leadership. It also would increase America’s $25 trillion debt load.

These are just some of the reasons that our respective organizations signed on to a coalition letter urging the federal government to reject a bailout of states for items not directly related to the pandemic.

I agree.

Bailouts with strings attached

From two people at the Illinois Policy Institute, at the Hill: State bailouts should come with strings attached

Conditioning bailouts on reform is already the norm across the world in both the public and private sectors. It’s the model used in the 2007-2009 bank bailouts, the corporate financial assistance under the recently passed CARES Act and the European Debt Crisis that struck in the wake of the Great Recession.

In 2010, the government of Greece had taken on so much debt that public services were suffering and there was no clear path to repayment. The biggest financial challenge was the Greek pension system, which by 2012 absorbed more of the nation’s gross domestic product than did pensions anywhere else in Europe.

So, when the “the Troika” — the European Commission, European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund — stepped in with a rescue package, pension reform was chief among their conditions. Greece was asked to strengthen the link between employee contributions and payouts, raise retirement ages and consolidate its scattered funds. The changes drastically reduced the cost of pensions while making the system more sustainable for retirees.

So, I haven’t been keeping up with what Greece actually did re: pensions. But they’ve been doing a kind of hokey-pokey with retirement ages and more, loosening some of their reforms.

First and foremost, recipient states must have sound pension systems under generally accepted actuarial principles, meaning they are on a path to fully funding their promises over no more than 25 years without increasing taxpayer costs. States that cannot meet this condition should be required to reduce pension liabilities to the level they can sustain and afford within these constraints.

Second, Congress should require states to maintain end-of-year balanced budgets and prohibit counting intergovernmental transfers and short-term borrowing as “revenue” for that purpose. Illinois is one of just 11 states that doesn’t require the budget to balance in practice — the state constitution has a “planning only” requirement —which has allowed it to spend beyond its revenues for 18 consecutive years and accumulate a $7 billion backlog of unpaid operating bills. From 2003 to 2017, the budget was propped up by nearly $38 billion in one-time revenue gimmicks.

Finally, states should be required to have rainy-day fund protections in place, including automatic deposits when the economy is growing and restrictions on when withdrawals can be made. In line with expert recommendations, states should have a target and a plan to hold 5 to 10 percent of their annual revenues in reserve.

Again, the problem I have with this supposed strings attached approach is that the strings wouldn’t stay attached.

Due to federalism, yadda yadda, the feds may be able to apply some short-term conditions on sending the money. But the money, once gone, will be difficult to claw back. Even if it were in the bill, all it takes is a change of Congess/President.

I’m sorry federal government, but you cannot enforce sane fiscal policy on the states.

Interlude: A Comic

Yanked from Powerline:

Yes to bankruptcy

Before linking, I will note that I have written a few papers with this author, Gordon Hamlin, Jr. He’s a lawyer [and I am not].

With that preface, I give you Gordon Hamlin’s piece at The Hill [yes, they are running a lot of these pieces, and for good reason]: The sky is not falling: Chapter 9 can help rescue and secure state and local pensions

If political leaders can set aside the heated rhetoric, there’s an opportunity to put troubled pension plans on a sound footing, thereby saving those plans for public employees and retirees while also helping to stabilize state and local finances.

Two years ago, along with Andrew Silton (an attorney), Mary Pat Campbell (an actuary) and the late Jim Spiotto (perhaps the country’s leading Chapter 9 bankruptcy expert) we published an article titled “Embracing Shared Risk and Chapter 9 to Create Sustainable Public Pensions,” in which we discussed how states and local governments could transition their underfunded public pension plans into a more secure and sustainable solution through the use of pre-packaged Chapter 9 Plans of Debt Adjustment. We focused on the New Brunswick Public Service Shared Risk Plan, although laudable elements of risk-sharing also exist in plans like the Wisconsin Retirement System, the Pension Fund of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), and the Board of Pensions of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

……

So, how does Chapter 9 help get us to this better place?With the freefall in tax collections — property, sales, hotel occupancy, and income taxes — virtually every local government potentially can meet the “insolvency” criteria for filing a Plan of Debt Adjustment under Chapter 9. About half the states have authorized such filings.

But here’s the key part of Chapter 9 that’s different from other bankruptcy proceedings: These filings have to be voluntary, and the bankruptcy judge can’t “cram down” any plan without the consent of at least one group of impaired creditors, who have to vote in favor of that impairment with a majority by number and two-thirds (2/3) by amount of the claims voted.

……

After carefully evaluating the requests by governors for $500 billion in relief and by counties, cities and mayors for another $250 billion, Congress should condition such relief aid on the commitment by states to transition their local government employees to a shared risk plan that can become fully funded (or better) within no more than 25 years (even shorter for better funded States). Alternatively, the relief should be given in the form of loans, which convert into grants when the transition is completed, along with secure funding streams.Second, Congress should amend Chapter 9 to exclude this relief aid from being considered as part of the cash flow and insolvency analysis that each local government must present with its filing.

There is more in the piece – I just want to share the heart of the idea.

Gordon mentions a paper we wrote with Jim Spiotto (RIP) and Andrew M. Silton. In this paper, Embracing Shared Risk and Chapter 9 to Create Sustainable Public Pensions, we talk about using pre-packaged Chapter 9 bankruptcies to achieve pension reform for municipalities. I am just fine with this process for municipalities.

I do not agree with using it for states. Sovereigns have got to take responsibility for their defaults and restructuring.

[And I could point to Puerto Rico, which isn’t even a sovereign power, as an example that even with federal oversight “bankruptcy” for a large polity doesn’t work too well. It’s still a mess. I have no idea how it will turn out.]

Gordon and I wrote a much longer paper detailing the idea. You can see a prior post where I wrote about it.

Ultimately, though, arguing about the legality/constitutionality of state bankruptcy is beside the point.

The actual bankrupt states – Illinois and New Jersey rise to the top here – do not have the political will to reform their pensions in a real way. If they had, they would have already made some progress. Illinois has had half-hearted reform attempts shot down because they actually have to amend their constitution first. They have never come close to trying that, not for pensions. Not in fifty years.

New Jersey hasn’t really even tried. They prefer stunts that don’t improve fund solvency at all. I will have more to write about New Jersey in my “States Under Fiscal Pressure” series I’m writing now.

So, yes, I object to state bankruptcy from first principles of governance, but I realize it’s all just an intellectual argument without much impact of anything.

Bailout and require honest accounting

I have seen multiple variants of this.

John Hood in North Carolina writes: Treat federal aid as shock absorber

When considering how best to structure federal aid, I think the best image to keep in mind is a shock absorber. Washington should, indeed, allow states and localities to use federal funds to help cover immediate shortfalls in revenue. While they will still have to make cuts in some areas and hold the line in others, governments should try to protect core public services as much as possible — as well as the jobs and salaries of the public employees and private vendors who deliver them.

However, because money is fungible, a completely hands-off approach to federal COVID-19 relief would allow profligate states and localities to service preexisting debts at the expense of taxpayers in other places. So, I think as a condition for accepting any new round of federal funds, governments should be required to restate their unfunded liabilities using honest accounting and then submit a clear plan for discharging the debt.

If a government fails to submit such a plan, or to implement it consistently, Washington should then convert its COVID-19 relief from a grant to a loan — and at a punitive rate of interest.

Sheila Weinberg of Truth in Accounting writes at The Hill [yes, I know]: Federal aid to state and local governments should rely on real numbers

Instead of basing the federal aid packages on educated guesses, if Congress is going to provide aid to the governments, the program should be based upon actual revenue losses. All the states, except California, have issued their fiscal year (FY) 2019 audited financial reports, and cities are in the process of producing their FY 2019 reports. The federal aid should be based upon the actual revenue amounts reported in these audited statements.

Each government’s revenue shortfall can be determined by comparing the revenue earned each quarter based on their FY 2019 reported amount and the current quarter’s earned revenue. The shortfall would be the amount of federal aid the government would receive for that quarter. The federal aid would not cover revenue losses that result from state or local legislative measures, such as tax cuts. The program would be for a two-year period with the first reporting quarter beginning April 1, 2020.

FY 2019 earned revenue would be derived from each government’s Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances for Governmental Funds, which include the general fund, special revenue fund and governmental debt service fund. Federal revenue should be excluded from the calculation because that money will be received from other federal programs.

I happen not to agree with Sheila, because this will shovel more money to high-taxing states than low-taxing states [especially states that are dependent on too few rich people]. I don’t think this sort of behavior should be rewarded.

I’m just fine with doing a per capita allocation. That’s fair.

A no bailout trio

Former governor of Wisconsin Scott Walker: Don’t Bail Out the States

Concerns about the economy are real. Instead of bailing out state governments, the federal government should focus on helping workers and small businesses — the taxpayers — get back on their feet. Failure to do so will continue to hurt state economies, saddling them with insolvent balance sheets.

…..

Second, federal funding is likely to diminish over time, creating further holes in state budgets. Shortfalls created by the disappearance of federal stimulus funds was a primary reason for the budget crisis that many state governments faced after the last recession.As The Times reported a decade ago, “Officials repeatedly warned states and districts to avoid spending the money in ways that could lead to dislocations when the gush of federal money came to an end.”

The article continued, “But from the start, those warnings seemed at odds with the stimulus law’s goal of jump-starting the economy, and the administration trumpeted last fall that school districts had used stimulus money to save, or create, some 250,000 education jobs.” A year later, many state and local governments were near bankruptcy.

Thus, the state bankruptcy talk in 2011.

Kay C. James of the Heritage Foundation: Do Not Bailout States for Years of Fiscal Mismanagement

Bailing out states is, simply put, a bad idea. It shields politicians from the consequences of their actions and encourages the same reckless spending habits that got them into a financial mess in the first place. That wouldn’t just harm the rest of us federal taxpayers; it would also do long-lasting harm to their citizens: When federal taxpayer funding runs out, the reckless spending and bigger budgets remain, and states will just raise taxes on their own citizens to make up the difference.

Federal bailouts of the states in the early 2000s and in the Great Recession of 2007-09 show us that these fiscally irresponsible leopards seldom change their spots.

In 2003, states received $20 billion in federal aid, but instead of balancing their books, many states just increased their spending and debt.

….

There is an old adage that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. The insanity of state bailouts must end. Sending mismanaged states hundreds of billions of dollars in bailouts is basically like giving a drug addict money and telling him not to buy drugs with it.

$20 billion is a lot less than the trillions being pushed now [even inflation-adjusted]. I doubt throwing more money into the hole is going to help things.

Richard Salsman at AIER: The Plan to Have Red States Bail Out Blue States

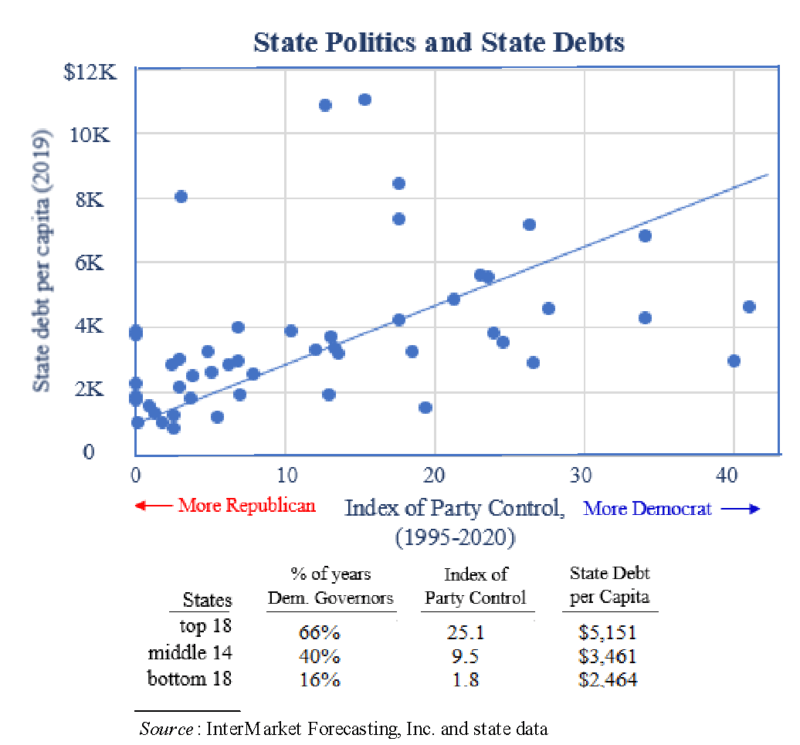

The nearby exhibit relates partisan control of the fifty American states over the past twenty-five years (1995-2020) to current state debt (per capita). My key premise is that current indebtedness largely embodies cumulative budget performance over recent decades; greater indebtedness reflects the long-term dominance of chronic deficit-spenders while lesser indebtedness reflects the dominance of budget-balancers. Next, we can ask whether party control relates to indebtedness.

Ehhhhh, as a regression, it leaves much to be desired.

Should the HEROES Act be enacted with the provision of $1 trillion in state aid, and if, as is likely, it directs relatively more aid to states with greater needs (indebtedness), it would be akin to red (Republican) states bailing out blue (Democratic) states. Partisanship aside, the aid provision would punish those citizens and officials who have been fiscally responsible over the years, while rewarding those who have been fiscally reckless. Not only would the policy be unjust, but in setting so terrible a precedent, it would only incentivize still further fiscally reckless behavior.

I want you to look, again, at the regression graph. There are a few states that are pretty far to the left [i.e., more Republican-controlled] with pretty high per capita debt levels. I notice he didn’t both to label the data points.

Mmmmm, I would love to redo that graph.

I do agree with him that the indebtedness of a state is the work of many years of deliberate choices, not merely a few years of “bad luck”.

The ants and the grasshopper

And finally, the WSJ editorial board [who mainly live in NY]: Should Florida Bail Out New York?

Democrats want a $915 billion budget bailout for states and cities, and the leading lobbyist is New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. His main public antagonist on the subject is Florida Senator and former Governor Rick Scott. Both men were first elected Governor in 2010, so let’s do the math to consider which state has managed its economy and finances better over the last decade.

…..

Democrats in Albany are claiming to be victims of events that are out of their control. But they have increased spending by $43 billion since 2010 — about $570,000 for each additional person. Florida’s budget has increased by $28 billion while its population has grown 2.7 million — a $10,400 increase per new resident.

……

New York’s spending on worker retirement benefits has nearly doubled since 2010 and is six times greater than Florida’s. Its debt-service payments have also doubled. Albany’s biggest cost driver is Medicaid, which gobbles up 40% of the state budget — twice as much as education. Florida spends about the same on schools as on Medicaid.Blame New York’s cocktail of generous benefits, loose eligibility standards and waste. New York spends about twice as much per Medicaid beneficiary and six times more on nursing homes as Florida though its elderly population is 20% smaller. Many New York nursing homes and hospitals are organized by unions, which use their political clout to drive generous pay and benefits.

……

Mr. Cuomo pleads poverty by claiming New York is a “donor” state to the federal government. But federal dollars account for about 35.9% of New York’s spending compared to 32.8% of Florida’s, according to the Tax Foundation. New Yorkers pay more in federal taxes than what Albany gets back because the progressive federal tax code hits high earners the hardest and New York still has many high earners. The “donors” are individuals, and the money isn’t Mr. Cuomo’s.

…….The policy question is why taxpayers in Florida and other well-managed states should pay higher taxes to rescue an Albany political class that refuses to restrain its tax-and-spend governance. Public unions soak up an ever-larger share of tax dollars, but Albany refuses to change. Mr. Scott is right.

I live in New York, and the members of the WSJ editorial board probably do, too.

But we agree that Florida need not pay for the high-on-the-hog lifestyle of the New York government.

Hey, I like the art in Empire Plaza….

…but I and other New Yorkers should be paying for that, not people in Florida [though, yes, some people who are in NY almost half the year spend an awful lot of time in low tax Florida. Officially.]

Much of this does remind me of the Aesop fable of the ants and the grasshopper. The grasshopper never spent any time preparing for the lean times, and so the ants, who did, are not very sympathetic to its plight.

When Pixar got a hold of the story, the grasshoppers terrorized the ants, and thus plundered the fruits of their hard work.

[and then the main grasshopper got eaten by a bird after being counter-terrorized by a fake bird built by the ants… okay, you know what? It’s not the best parallel.]

But New York and Illinois and many other profligate states take whatever money given to them, and try to build up new obligations, and then whine and bluster when the inevitable downtimes come again.

It is odd, given that the politicians in both Illinois and New York seem to take the job as lifelong careers, so must deal with multiple cycles. I guess they’ve been able to enjoy the fat money times so much because of the Baby Boom lofting the demographic wave….. and those Boomers are now mostly retired.

But that…. is for another time.