Original Sin (or Pandora's Box) and Public Finance and Pensions

No Silver Rule in public finance, alas

I think there are two inherent types of problems, or situations, in the human condition.

The first, I would argue isn’t a true problem. It’s that something is wrong, and we don’t know what to do.

Now, we might be able to figure it out, eventually. Or it might be something that is, at its core, insoluble. It’s just the condition of the universe. That sort of thing. Maybe I would call this a challenge (and if I were the annoying, peppy, marketing type… an “opportunity”! YAY!) — but it’s not exactly a problem. It just is.

But the second thing — and you’ll note I didn’t give examples of the first, but I will give an example of the second — is definitely a problem. Because usually what people do is make it worse. And then it becomes a disaster.

Not wanting to do the thing…. or doing the one thing you’re not supposed to do

This is the second kind: knowing what you have to do to fix a problem, but not wanting to do it. Or, very relatedly, knowing that everything would be fine, just so long as you don’t do this one thing…. but you do the one thing.

Sound familiar?

The Christian version of this is Original Sin. As Chesterton wrote, it’s “the only part of Christian theology which can really be proved.” [Proof: just observe how humans behave]

The Classical Pagan version is Pandora’s Box.

And here we come to public finance and pensions.

I’ve been blogging more about mortality of late, and less about public finance and pensions, partly because I have found public finance so depressing over the past year. The federal government turned on the printing presses, threw a bunch of newly-printed money into a black hole, and I couldn’t see beyond the event horizon. Not at the time, at any rate.

Maybe the state and local governments would put the money to paying down pension debt and not promising more. Maybe money would be used prudently.

Maybe.

I didn’t want to look too closely last year.

So let’s look now.

Financial state of the cities – got worse

Truth in Accounting has released their annual report on the financial state of 75 large U.S. cities (don’t go looking for NJ cities, btw, because they don’t behave well in their financial reporting — now there’s a surprise.) Here’s a link to their 2022 release.

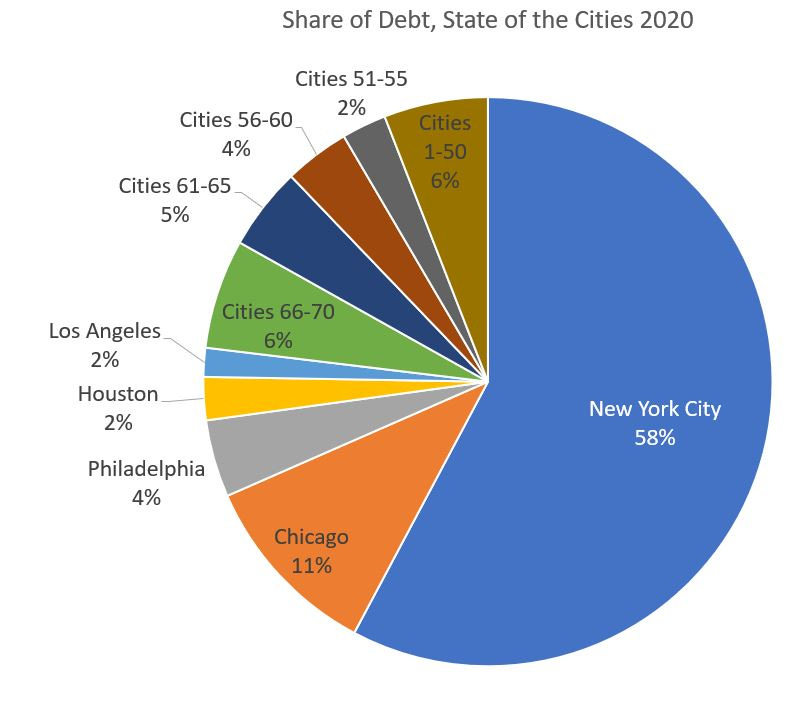

I wrote about the report two years ago, and while I do not like pie charts in general, I think this one tells the story I want to tell from the 2020 report:

Yes, New York City’s debt by itself was about 60% of the entire report’s debt. In the report released in January 2020, before the pandemic hit. New York City, the city very dependent on tourism and the financial sector, and specifically, people living in Manhattan and paying taxes to NYC.

Do you think it got better in the 2022 report?

The answer we’re looking for is no. Indeed, it’s so bad, they had to break the scale on which they graphed all the cities’ taxpayer surplus/burden, because otherwise, you’d barely get to see the others.

Here’s top 5/bottom 5 graphed:

So the ones that are “sunshine” haven’t accrued much in the way of a surplus per taxpayer, which is as it should be — it’s okay to have some cushion, but they have no business in accruing a bunch of cash they’re doing nothing with. That’s asking for shenanigans.

But what’s going on in NYC is pretty awful in terms of its finances. It got much worse compared to 2020 — the per taxpayer burden grew 13% in just two years.

Let me just quote the report:

(75) NEW YORK CITY remained in last place because it needed more than $204.4 billion to pay its bills. The city’s finances continued to deteriorate as the amount of unfunded retiree health care promises ballooned to more than twice the amount of unfunded pensions. The city’s pension plans are 78 percent funded, but the city has funded only three percent of the $117.4 billion in other post-employment benefits that employees have earned and been promised.

So, that is something that is not getting fixed any time soon.

Innovative ways to fund the public pensions and retiree healthcare: fund them when you made the promise

This brings me to the next item.

I didn’t comment on it at the time, but back in September 2021, a competition for Innovative Public Pension Funding Strategies was announced, which may or may not have closed recently. I had gotten some notice that they had extended time on applications, which is almost always an indication of a pitiful number of applications. Or they weren’t happy with what had been submitted.

I have submitted applications to competitions/requests for papers like these in the past (you can see some of that work in these posts: A Proposal: Restructuring Current Public Pensions Through Municipal Bankruptcy and Causes of Public Plan Insolvency: On Public Pension Valuation — this went over like a lead balloon), but I didn’t even bother with this one.

Because this was my innovation:

ACTUALLY FUND THE PENSIONS AT THE TIME YOU MAKE THE PROMISES.

DON’T PROMISE WHAT YOU ARE UNABLE TO FUND.

That would definitely not have been a popular “innovation”.

However, it would have been quite the breakthrough.

Seriously, enough snark — there do exist public pension systems like that already, but they are under-represented in the public pension space, sadly.

The thing is, the problem of underfunded pensions is also not new, because forever people have not wanted to pay for the promises they made. They would rather pay you next Tuesday for that hamburger today. That’s what pension promises are, right? We promised to pay you later, so why put in money now?

(note: a practical lesson in why public pensions should be pre-funded.)

Even after all the practical lessons in the necessity of being moderate in promises and to pay for promises when they’re made, politicians and public employees keep looking for “innovations” to fix a problem that comes from not wanting to do the very simple things they know would work: make moderate promises and pay for them fully when they’re earned.

The welcomed messages: one clever trick

The kinds of messages that are welcomed are “innovative” in terms of telling you that you don’t have to do the thing you really don’t want to do (put more money into the pensions, promise less, cut back on many things, tax more, etc.)

Yes! You don’t have to fully-fund pensions!

Absolutely, pension obligation bonds will allow you to do really real arbitrage! Don’t worry about the extra leverage!

For sure, you should be chasing the waterfalls of alternative asset classes! You can get those high returns and not worry about extra risk! Otherwise, you’d have to decrease your discount rate!

Public pensions: when does the disaster come?

I haven’t been writing much about public pensions during the pandemic because of all the federal bailout money papering over cash flow issues in the states. Not only have they been flush with the direct bailout funds, but their state income tax flows have been strong, inflation has boosted stock market prices as well, and the numbers, on paper, have looked pretty good so far.

The balance sheets, as we see above, don’t necessarily look good. But the liquidity has been fine, and as far as it goes for politicians, as long as they can get their hands on cash, whether from taxpayers, bond buyers, or the money printers, they do not care. Where an insurer or private pension plan would be taken over well before the conditions many of these governments are in, there is a lot of financial ruin to be found in a government. Both NYC and Chicago seem to be continuing to roll along, at least for now.

Meredith Whitney ran into trouble because she had prognosticated that muni bonds would run into trouble shortly because she had seen the balance sheet troubles of governments, which aren’t the same as cash flow troubles. Even there, Puerto Rico has shown even absent financials anybody can rely on, a government entity can roll on for quite a while before being forced to cut anything at all. What would cause trouble for a private company is not the same thing that causes trouble for a government.

All that said, governments may start running into cash flow issues. Sure, the federal government can turn on the money printer. All those years of running it and seeing no appreciable inflation in consumer goods lulled the Federal Reserve and Congress, I suppose. However, they may be running up against the demographic reality of the peak of the Boomers finally reaching retirement (oh, you didn’t know they hadn’t yet? The peak Boomer birth year was around 1957/1958. They turn 65 this and next year.)

And no, COVID didn’t kill off enough retirees — yet — to reduce promises to them by enough to make much of a difference. Sorry if you were hoping that. Given the deepness of the funding holes in places like Chicago and NYC (and I will return to that in future public pension posts), it would take at least a 20% permanent increase in mortality to get a noticeable effect. Not two years’ worth of extra mortality.

Please stop making it worse

The issue is that I knew the worst plans, the worst places, the worst politicians would all be getting together to make things worse.

We saw that with New York City above. NYC didn’t do anything in particular to make things worse, exactly (other than the whole “let crime run rampant” thing — that doesn’t exactly tell the people with money to stick around). They just didn’t do much to make anything better. A bunch of money dropped on them… and pretty much no improvement in the balance sheets.

But Chicago — oh, Chicago and Illinois:

Illinois State Senator Robert Martwick (D-Chicago) is pushing ahead with legislation that, according to a Bloomberg report, could increase Chicago’s police pension obligations by another $3 billion in total through 2055. An earlier city estimate put the cost at $2.1 billion. Senate Bill 2105 would do that by removing a birthdate restriction on eligibility at age 55 for a 3% automatic annual increase in retirement annuity.

Where would Chicago get money to cover the additional liability? No answers.

It’s a repeat of a similar bill Martwick championed for the Chicago firefighters’ pension, which was signed into law by Gov. JB Prtizker in April. As reported by Crain’s on Wednesday, the cost to Chicago of that new law has now been estimated at $700 million, which will require additional annual contributions from city taxpayers estimated to start at $16 million in 2022 and ramping up to reach $24 million by 2055.

I’ve written about the Chicago police and fire pensions and the Chicago pensions generally. Many times.

I’m not going to do a Meredith Whitney and predict that the money will run out, because clearly there are plenty of people continuing to throw money at Chicago and Illinois.

For now.

But this is what we’re seeing for the contribution pattern for Chicago Police pensions:

The blue portion of the bars is what was actually paid, the red portion the unpaid. As it stands, even before a benefit boost, they’re approaching 90% of payroll as “required” contributions. And they’re not even making 80% of that.

A benefit boost would make that red bar even higher, obviously.

The money does run out, eventually. The balance sheet issues for the pensions points to future cash flow problems. The contribution requirements now, which are not being met, point to future cash flow problems.

The problem is that future problem does get closer and closer.

And because they tell themselves they’re being “clever” and “innovative”, they bring that future disaster ever closer.

So that’s something for us to look forward to.

In any case, I will be returning to blogging on mortality for my next posts, looking to the happier topics of external causes of death, like suicide, homicide, drug overdoses, and motor vehicle accidents.

At least in those cases, nobody is fooling themselves that they’re making innovative or clever choices.