Not With a Bang, But a Whimper: Demographic Decline Undermines Public Finance

Difficult to pay more later when population is shrinking

I’m not quite sure why this is “news”.

NYT: Long Slide Looms for World Population, With Sweeping Ramifications

Like an avalanche, the demographic forces — pushing toward more deaths than births — seem to be expanding and accelerating. Though some countries continue to see their populations grow, especially in Africa, fertility rates are falling nearly everywhere else. Demographers now predict that by the latter half of the century or possibly earlier, the global population will enter a sustained decline for the first time.

A planet with fewer people could ease pressure on resources, slow the destructive impact of climate change and reduce household burdens for women. But the census announcements this month from China and the United States, which showed the slowest rates of population growth in decades for both countries, also point to hard-to-fathom adjustments.

The strain of longer lives and low fertility, leading to fewer workers and more retirees, threatens to upend how societies are organized — around the notion that a surplus of young people will drive economies and help pay for the old. It may also require a reconceptualization of family and nation. Imagine entire regions where everyone is 70 or older. Imagine governments laying out huge bonuses for immigrants and mothers with lots of children. Imagine a gig economy filled with grandparents and Super Bowl ads promoting procreation.

“A paradigm shift is necessary,” said Frank Swiaczny, a German demographer who was the chief of population trends and analysis for the United Nations until last year. “Countries need to learn to live with and adapt to decline.”

It is important, but these results have been projected in the past. This has been known since the Baby Boomers failed to have enough kids themselves. Heck, I’m in Gen X, and most of us are too old to birth additional children now, too.

Past projections showed population growth would slow

Even if the U.S. Census people were a bit optimistic on immigration projections, it was always in the cards that population growth would slow.

The last time the Census Bureau did a population projection, the estimated population for even 2020 came in a little high. From March 2018: Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060 — they estimated a total population of about 332.6 million, and the apportionment Census results were 331.1 million. To be sure, this is a less than 0.5% difference, so no big deal.

This is the growth rate they projected, even in 2018:

2020-2030: 7%

2030-2040: 5%

2040-2050: 4%

2050-2060: 4%

Those are full-decade growth rates. That’s before the pandemic has shaved our numbers down a little.

Would you like to know the growth rates from prior decades?

2010-2020: 7%

2000-2010: 10%

1990-2000: 13%

1980-1990: 10%

So yes, there was higher population growth in the past. It’s been slowing. And our projections have been that it would continue to slow down.

News from the 1980s

We’ve known this issue for decades. This first came up in the “baby bust” during which Gen X was born, in the 1970s. Here, have an article from 1985, talking about the phenomenon:

In the ’70s, these overpopulation alarms had widespread impact. A 1970 survey found that 69 percent of married women in America agreed that US overpopulation was a ``serious problem’‘ — and that many of them were lowering the number of children they intended to have.

Now, however, the birthrate in the industrial world is below the ``replacement rate’‘ of 2.1 children per woman. That rate is set at the number of children needed to replace every parent, with more added to account for mortality.

In 1855, white American women averaged 5.31 births — well above the then-current replacement rate of 3.32 (higher then because of higher infant mortality). By 1980, the figure had dropped to 1.75 children each — well below the 2.1 replacement rate. Even the high birthrate of US Hispanics — 56 percent more than non-Hispanics in 1982 — doesn’t raise the total US rate above replacement levels.

Again, that was from the 1980s. And our TFR is about 1.7 now as well.

It’s not surprising.

It has been known for a while that even optimistic immigration assumptions wouldn’t have the U.S. population growing at the level public finance planners seem to use.

Japan leads the way in shrinking population

Unsurprisingly, Japan has led the developed nations in hitting the demographic turnaround: their population has been shrinking for over a decade now.

Their population peaked at 128.1 million in 2008 and was down to 126.4 million in 2018.

Many fault Japan for its restrictive immigration policies, and I will return to that.

It is the oldest nation on the earth, in terms of percentage. 28 percent of Japan’s population is age 65 or older. Contrast that to the U.S., where only 16% of our population is age 65 or older (okay, probably a little less now, after COVID). Contrast that to Japan, where 16% of their population is age 85 or older.

Don’t expect a birth rate boost

Brookings: Will births in the US rebound? Probably not.

Recently released official U.S. birth data for 2020 showed that births have been falling almost continuously for more than a decade. For every 1,000 women of childbearing age (15 to 44), 55.8 of them gave birth in 2020, compared to 69.5 in 2007, a 20 percent decline. The “total fertility rate,” which is a measure constructed from these data to estimate the average total number of children a woman will ever have, fell from 2.12 in 2007 to 1.64 in 2020. It is now well below 2.1, the value considered to be “replacement fertility,” which is the rate needed for the population to replace itself without immigration.

However, the total fertility rate calculated from annual birth data might be a misleading indicator of actual future fertility rates. It is only an appropriate indicator of the total number of children women will have, on average, if the age profile of childbearing is static. As some have pointed out, women today might just be delaying their births, but they could go on to ultimately have the same number of total children, on average, as women before them. If so, today’s low birth rates will rebound in future years, and the current decline will prove to be a temporary phenomenon. Alternatively, if women both delay childbearing and do not compensate with more births at later ages, the recent decline is likely to reflect a persistently lower level of births.

Here is a graph showing actual trajectory by cohort (unlike the way these data are usually presented):

The 1975 cohort – which is closest to mine (I was born in 1974) – actually managed to have enough kids to replace ourselves. (I did my part, with 3 kids). Those born in 1980 are close behind, but lower… but yes, there is a notable drop for those younger generations.

The Brookings folks go on to project an ultimate number of children ever born per woman to range from 1.4 to 1.9, for women born in the year 2000. That seems a reasonable range to me, given recent history.

Again, the current TFR (which has the same shortcomings as calendar year life expectancy), is about 1.7 in the U.S. Theoretically, it could increase a huge amount… but I’m not counting on that happening.

Don’t assume immigration will save us

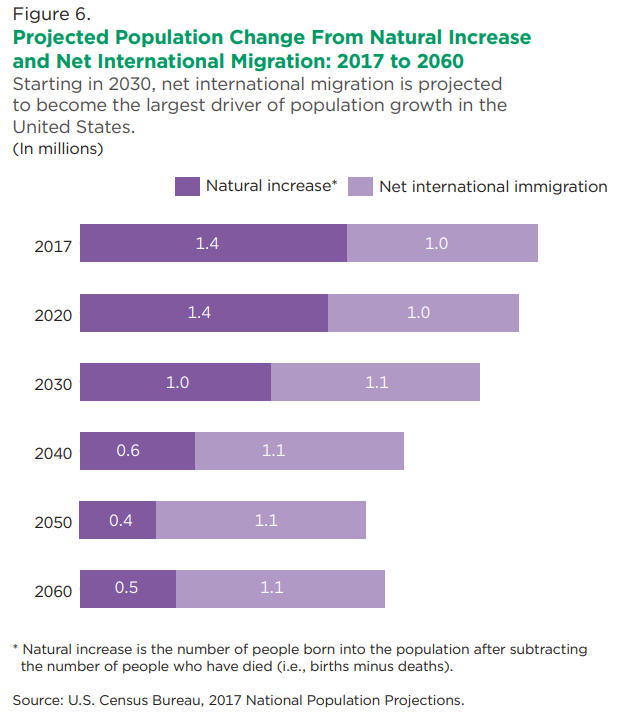

By the way, here’s how the “natural increase” (aka births > deaths) and net migration components break out in the U.S. Census projection from 2018:

The projection assumes an approximately constant contribution from immigration, but decreasing births minus deaths (part of this is due to deaths increasing as a raw rate, as the population ages).

Of course, immigration could shoot up by a lot – after all, there are far more people outside the U.S. than in it, and we still are a top destination for immigrants, whether legal or illegal.

There are places in the world where birth rates have been pushing up growth, but the trajectory for almost all countries and regions of the world is a falling birth rate.

From the World Bank, the following table shows the most recent total fertility rate estimate for regions, plus a sparkline showing their historical trend:

Observations:

North American TFR is flat. It has been for decades. That includes Mexico, by the way.

The historical trend has been decreasing fertility everywhere, and the places with the lowest seem to have hit a “flat” point

The only places with really high fertility are the Middle East and Africa (okay and the small island nations of the Pacific), and even they have shown decreasing fertility

More to the point: if immigrants pour into the U.S. in future decades and get the population at high growth again, are they really going to be interested in paying off decades-old debts instead of having their taxes paying for current services?

“Pay more later” doesn’t work when people aren’t there later

I focus mostly on public pensions when it comes to public finance, but what I’m about to say extends well beyond pensions: so much of the financial “planning” for governments come with a tax base positive growth assumption.

Then there are the various investment return assumptions, which indirectly is tied to population growth. I am definitely an acolyte of Julian Simon, who argued that humans are the ultimate resource, but more to the point: all economic value comes from humans.

You achieve investment returns in a couple of ways: the asset throws off a series of cash flows to you (interest payments, rents which other people are paying) or you sell the asset to somebody else, at what you hope is a higher value.

If there are fewer people coming behind to buy those assets or to produce economic activity, you’re going to have a hard time achieving the return you wish.

Some say inflation will save public finance… but only to the extent that their liabilities aren’t inflation-linked. That’s true for normal GO bonds, but not for their pension liabilities. Public employee unions will not just sit around to see their pay erode, much less their pension benefits. If there is an inflation cap on pension COLAs, then what ends up happening is that retirees get less than what they thought they’d get, in terms of real buying power.

Some say the governments need to tax the rich harder! The problem here is not just that rich people are good at legally dodging taxes (they didn’t get rich by accident, usually), but that the rich got rich via value from other people. If those other people aren’t there… they’re not really all that rich.

It is true— taxation for the U.S. could increase:

But it’s not clear to me if these taxation metrics are including local taxes (such as sales taxes and state income taxes). It would be nice to do a state-by-state comparison.

In any case, even if taxation did increase in the U.S. to European levels, people would know that it was to cover promises made decades ago, not to pay for government services now. This would not be popular.

I expect fundedness ratios of public pensions to decrease and in some cases for the assets to run out.

It was difficult to meet what was called full pension contributions before, with those contributions calculated assuming more would be paid later.

The big problem with the “pay more later” idea — which is “we can’t pay much more right now, but because of growth/inflation/whatever, we’ll be able to pay more later” in longer form — is that it doesn’t necessarily become easier to pay more in the future.

That growth doesn’t always show up, so the promises continue to get short-changed, and everybody ends up with less than originally “planned”: taxpayers pay more (thus get less in net income), citizens get less in services, pensioners get less in benefits (because they’re inflated away or have to take benefit cuts). It can easily be a lose-lose-lose situation.

To be sure, things can change and can change relatively rapidly in a short amount of time. But the scenarios that make that happen will have a lot of pain baked in.

There can be an even worse pandemic, killing off more old people, so that the benefits can still be supported. That would take something much worse than COVID-19. I would rather not think about that scenario, which may have so much disruption that reducing the old age liability doesn’t make up for the economic loss for those at younger ages.

A happier thought is another baby boom — the post-war Baby Boom itself came after a time of relatively low birth rates in the U.S. due to the Great Depression. But such a large change would have its effects 20 years later in expanding GDP.

The real problem is right now, with the demographic anomaly that is the Baby Boom in their senior years and a much smaller Gen X in their peak earning years.

There are not enough of us Gen Xers and Millennials to support the Boomers, and all the public fiscal promises they made to themselves.

Ending with a whimper, as foreseen for decades

So something will give… and it’s likely to be a slowly eroding situation more than a “bang”.

I will likely be around to watch all of this unfold (fun!), but the one thing I will not tolerate is anybody saying this was unforeseeable. Not only was this foreseeable, but it has also been foreseen for over 40 years.

Unlike the warnings about the population bomb or global cooling, these demographic projections based on assumed lower birth rates have borne out over the decades.

Those who like to make long-term forecasts should be happy that at least one set of forecasts have actually been close to reality.

To be sure, it was one of the easiest forecasts to make, but still. Get your wins where you can.