Yesterday, in normal times, would have been Tax Day. But that has been pushed off til July 15…. and that has cascading effects throughout governments.

[By the by, I just received my stimulus money today, and the way it was marked by my bank was as a tax refund from the IRS [I got my actual tax refund a couple months ago.]]

The Tax Foundation has had a good tracker of state fiscal responses to COVID, and many, of course, pushed back tax filing dates to be in line with the IRS. That delays the collection of state income tax, and many states get a boost in April due to this timing.

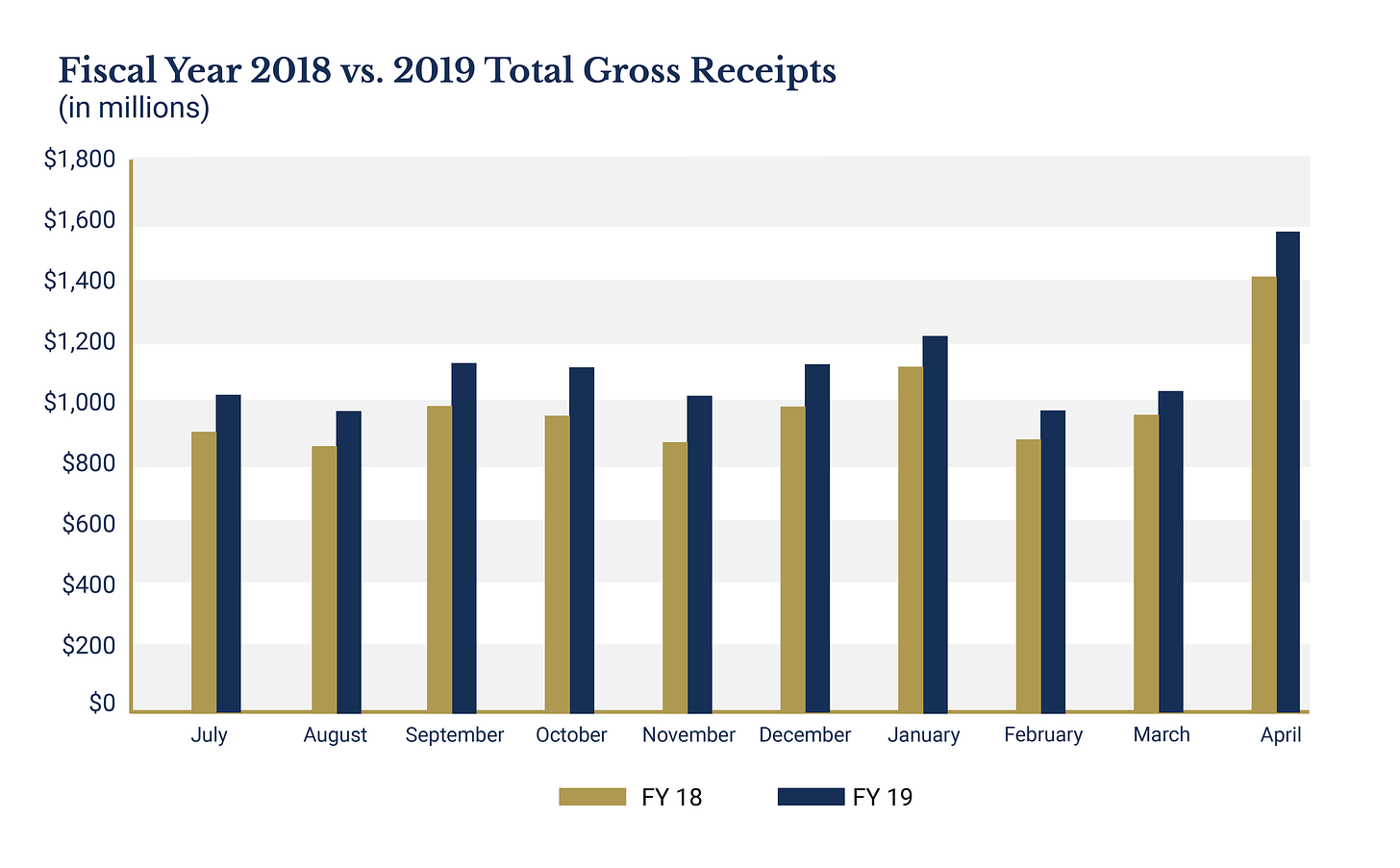

An example, from Oklahoma:

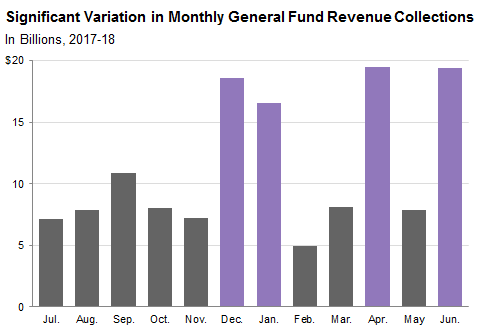

Some places, like California, have a lumpier pattern:

All of these patterns are driven by official deadlines, of course, and shoving things off by three months will likely depress income tax revenue for the states … not to mention all the other revenue hits they’re taking.

Revenue Projections for States

First, a tweet:

That’s for Illinois. Just so you can have something to compare to, in FY2018, general revenue funds were $36.8B. So this is about a 10% drop for FY2020, and almost 20% for FY2021.

New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli today issued a revenue projection for the 2020-2021 state budget which reflects an estimate of the economic impact and ongoing volatility stemming from the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19). DiNapoli estimates tax revenue will be at least $4 billion below the projections in the Executive Budget of $87.9 billion. He also offered one alternative scenario if a more severe recession or sharper declines in the stock market occur, which could lower tax revenues by more than $7 billion.

So that’s about 4 to 8% drop. Hmmm.

be the effects of the coming recession. Large scale “social distancing” will reduce consumer spending and workers’ wages and, in turn, cause sales and income tax revenues to plummet. State tax revenues declined by more than $120 billion—about 9 percent—during the Great Recession (Q2 2008 – Q2 2009), for example.

Seems to me that a drop of 4 – 8% on the revenue side seems a bit… optimistic.

Increases in unemployment will boost spending on unemployment insurance and make more people eligible for Medicaid, both of which state governments help finance. Lower taxes and increased demands for funding will impose severe strains on state and local budgets.

p.

Cut Spending? Don’t Be Silly

That’s a problem — especially if you’re like Connecticut, and instead of decreasing some spending, you’re set to actually increase it:

Democratic governors in New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia are temporarily suspending raises for state employees or freezing pay until they can better understand the fiscal impact of the pandemic, but, thus far, Connecticut state employees are still scheduled to receive a second pay increase, projected to cost taxpayers $353 million.

That’s just in additional cost. Not total cost.

The second round of wage increases is set for July 1, the start of the 2021 fiscal year, and is comprised of a 3.5 percent general wage increase, combined with an annual step increase of 2 percent.

The raises were included in the 2017 SEBAC agreement negotiated by Gov. Dannel Malloy. The Office of Fiscal Analysis estimated the cost at $353 million, although the actual annualized cost may be as high as $387.8 million.

The wage increases in July will be the second increase for state employees in two years.

And, of course, it could cost more.

Several states are furloughing workers, and during the Great Recession, many state and local governments actually shrank their workforces. I know many states and localities are looking to the federal money machine to go brrrr and let them continue their high-spending ways, but the House of Representatives, source of any money laws, plans to be out of session til May 4 [I mean, sure, they’ll come back if there’s an emergency, but you can see they don’t consider the current state of play an emergency.]

Funding the States Not a Congressional Priority

I see this story from last week on state governments asking for a $500 billion bailout.

National Governors Association Chair Larry Hogan, R-Md., and Gov. Andrew Cuomo, D-N.Y., the group’s top Democrat, are issuing a joint call for Congress to approve $500 billion in direct aid to states, signaling a deepening budget crisis caused by the coronavirus as Congress battles over the next round of funding.

….

States say they are still waiting for money included in the $2.2 trillion CARES Act. The bill included $150 billion specifically for states but it has not been released in the roughly two weeks since it was signed into law.

Guys, take a hint. State and local governments are not a priority to federal politicians. The House of Representatives sits atop the money machine and know they’ll always have theirs.

Yes, Joshua Rauh has argued DON’T BAIL OUT THE STATES, and there will likely be more pro-and-con pieces, but unlike with unemployment insurance boosts [which will strain state cash flow] and stimulus checks [money machine goes brrrr], sending a bunch of cash to states doesn’t give the politicians any sort of personal boost for re-election. What have the states done for us Congressfolks lately, huh?

So let’s see exactly where the states are hurting for their revenue.

Dependency of States on Sales (and Excise) Taxes

One obvious hit to state revenue is a drop in sales taxes as fewer people go out and shop on frivolities. To be sure, booze sales from stores may be up, but they’re obviously down from restaurants. As people drive less, gas taxes drop. So let’s see how dependent various states are on these taxes.

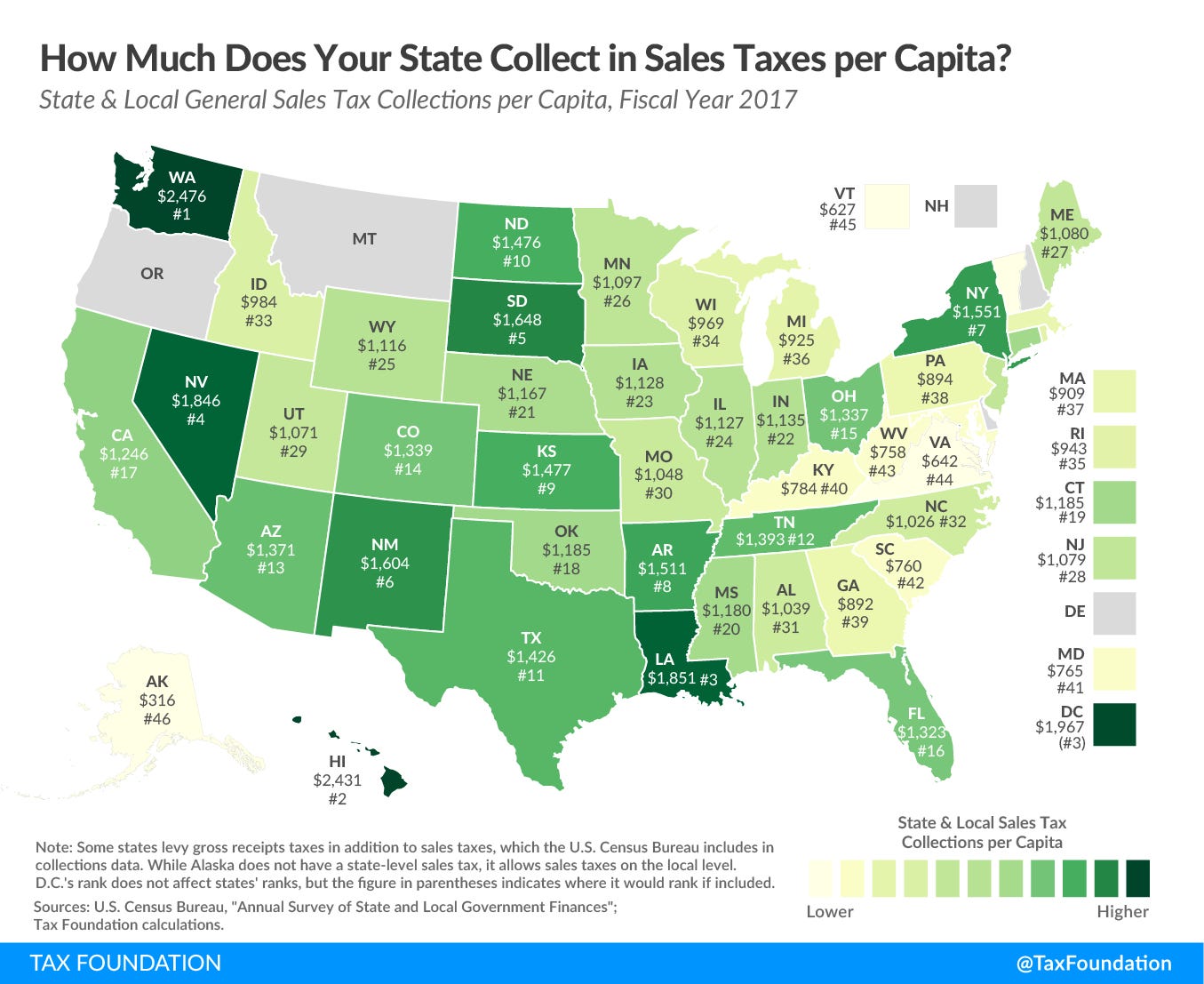

The Tax Foundation, as usual, has a handy sales tax per capita map:

Now, some places are going to be more dependent on sales [and property] taxes than others, having no income taxes. We’ll get to income taxes in a bit.

Dipping into news here and there, Mount Airy in North Carolina is expecting a 20% drop in sales tax revenue,towns in Texas are concerned, as almost a third of their revenue comes from sales taxes, and Shreveport knows a drop is coming… but aren’t putting a number to it.

In many places, public finance officials are not wanting to say a specific number, and they’re probably right in that decision, because the rapid drop is very different from prior recessions.

NYTimes: ‘Pretty Catastrophic’ Month for Retailers, and Now a Race to Survive

Retail sales plunged in March, offering a grim snapshot of the coronavirus outbreak’s effect on consumer spending, as businesses shuttered from coast to coast and wary shoppers restricted their spending.

Total sales, which include retail purchases in stores and online as well as money spent at bars and restaurants, fell 8.7 percent from the previous month, the Commerce Department said Wednesday. The decline was by far the largest in the nearly three decades the government has tracked the data.

Here is a graph of the month-to-month percentage changes [seasonally-adjusted].

Remember, things were shut down for many places only halfway through March, and many of us spent extra before the shutdown, in preparation.

If they compared April vs. February, I bet the difference would be stark.

But think on this: the people who really will be making the decision to open stuff up again — governors and state legislatures — can look at the huge drop in their revenues …. and they know that they, too, will ultimately be affected. Even if they do get a partial federal bailout.

Income Taxes are an Even Worse Source of Revenue

So, sales are obviously down… but what about income taxes? Maybe taxing the rich-who-can-afford-to-work-from-home… oh wait, the actual rich tend to get their wealth from owning businesses. Many of which aren’t making money. Then there are the finance people…. no, they’re not necessarily making a lot of money either.

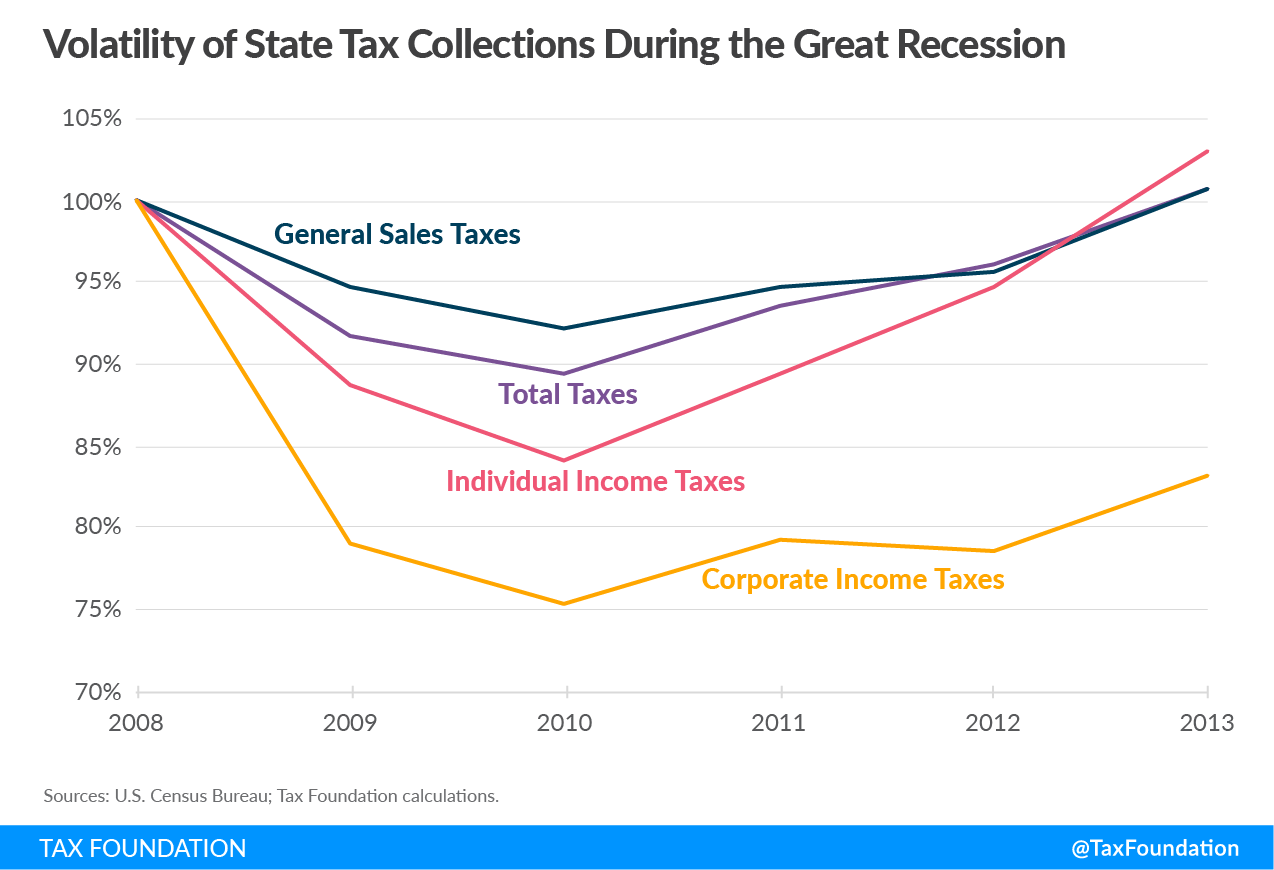

From the Tax Foundation: Income Taxes Are More Volatile Than Sales Taxes During an Economic Contraction

As a general rule, income taxes are more volatile than consumption taxes, as can be seen from aggregate state tax collections during and immediately after the Great Recession. By 2010, general sales taxes were down 8 percent from their 2008 peak, while individual income taxes fell 16 percent and corporate income tax collections plummeted a full 25 percent.

Luckily, corporate income taxes are not a big source of revenue for states [nor for the federal government].

Not only do you have income taxes drop down, but you also have a greater draw on state funds of Medicaid and unemployment payments. It’s a bad whammy to have.

How Long Can States Hold Out?

Many states are not feeling cashflow desperation yet, but really, anybody can see it coming. [except those in Congress, I suppose.]

Right at the beginning of all the shutdowns, Pew published a report on state rainy day funds – aka financial reserves.

Most states could last about a month. But that’s assuming “normal” expenditures. However, this may help explain a little bit which states are making which decisions…and some that have not yet cut their spending may find themselves forced to soon enough.

Tell Me Again Pay-as-you-go Is Fine for Public Pensions

I’m going to switch gears quite abruptly right now, and mention public pensions. And no, not about the contribution holidays I’m expecting from some states.

One thing I want to point out today: the never-fully funded folks should take this opportunity to look at the huge holes in their assumptions. Let me repeat a few assumptions from the September 2017 op-ed from three San Diego public retiree leaders: Why full funding of pensions is a waste of money. [That headline… whew.]

In the public sector, however, while governments may encounter periodic budget ups and downs due to economic cycles and fluctuating revenues, they are not going away.

The amplitude of the downs is kind of important. We are seeing quite severe downs right now.

Full funding of a public pension plan amounts to covering the total future benefits of all current workers. The Hass Institute analysis describes this as a waste of money because it equates to insuring against a city or county’s disappearance.

Maybe some public retirees would like that insurance, right about now, don’t you think?

Imagine you sign a lease to rent an apartment for 12 months at $1,000 a month. Your ultimate obligation is $12,000, but should the landlord refuse to rent to you if you can’t show you have $12,000 available at the outset of the lease (100 percent funding)? No, the landlord simply wants assurance you can pay your rent each month.

Yup. And now you don’t have those revenues to cover those payments. How do you feel now?

Each of these examples involves an ultimate obligation to pay off all the debt by a specific date. Public pensions are different in that the obligation is open ended, but so are the income sources.

And those income sources can be obliterated. If the income sources are not there when it’s time to pay the pension benefits…

I had plenty to say at the time, and even made a new “Hall of Shame” just for those who argued that it was fine for the pensions to be never fully-funded.

I will have more to say in later posts, but all I’m asking, right now, is for those who argued for approaches that increased the fragility of public pensions, which of your assumptions have been spectacularly broken by COVID-19?

Really think about it, because I know y’all are gearing up for “no, don’t worry about an asset death spiral” and “pay-as-you-go is just fine!” articles, and maybe you shouldn’t be writing them.

Because your credibility will be shot.

Just think about it.