National Public Pension Coalition vs. Truth in Accounting: Who is Accurate With Public Pension Unfunded Debt?

Public finance is hard.

A week ago, the National Public Pension Coalition posted Why Truth in Accounting’s Recent Claims about Pensions are Inaccurate. Back in October 2020, the group posted a similar piece: Texas Stands Up to Truth in Accounting.

There are some major points the NPPC (National Public Pension Coalition) makes in both pieces, and I want to address their main points, as it relates to regular reports that TIA (Truth in Accounting) makes.

Aggregating government financial information in a way taxpayers can understand

TIA (Truth in Accounting) puts out regular reports on the finances of different levels of U.S. governments.

I have covered some of these reports in the past:

February 2020: State of the Cities from Truth in Accounting

September 2019: Visualizing the Financial State of the States

Those two posts are a good representation of what I’ve done with their reports — I use their results to make my own graphs:

That’s a tile grid map showing the main measure TIA uses: a per-taxpayer deficit (redder) or surplus (black).

Their method is fairly simple, even if what they need to do can be labor-intensive. [And what I had to do to make my graphs took a bit of time on my end, too]

For each salient government entity, they look at assets on hand and stack it up against long-term liabilities, such as unfunded pension liabilities, retiree health care, and outstanding bonds (that aren’t associated with capital assets). This is about total indebtedness, not only pensions.

This is not about how good the government is at budgeting each year — this is a snapshot that gives an idea of their net balance sheet position, and both assets and liabilities can accrue over multiple years as a result of budget choices.

Then they have an estimated number of individual taxpayers, and just make a ratio to get taxpayer burden/surplus. It’s a debt (or surplus) amount, evenly divided by the current number of taxpayers.

Current obligations. Current taxpayers. It is based on present value which folds in potential future investment returns. It’s a measure intended to capture current financial positions, and cash flows themselves may differ in the future. This is a balance sheet perspective.

The general public usually isn’t told about balance sheet measures aggregated like TIA does. Often, it will be in isolation, such as the unfunded pension liabilities by themselves, or outstanding bonds by themselves, without looking at the big picture. It’s difficult for non-experts to try to figure out the magnitude of the government debt hanging over their state or local governments.

Most general reporting on public finance focuses on government budgets, which is more like an income statement… if it weren’t actually mostly a statement of cash flows. Rather than go down that rabbit hole, as our focus is the balance sheet point-of-view, I’ll point you to my related posts on cash-based versus accrual-based accounting for income statements:

April 2021: Public Finance: Full Accrual Accounting and Governmental Accounting Standards Board Testimony

January 2019: Governmental Accounting Standards Board: Meep Writes a Letter

In any case, in both the posts, the NPPC objects to the TIA taxpayer burden measure.

NPPC’s objections to the taxpayer burden measure

Let’s look at both posts mentioned at the beginning.

From October 2020, TEXAS STANDS UP TO TRUTH IN ACCOUNTING:

According to Truth in Accounting, their annual report is designed to survey the financial well-being of each state’s economy. As they maintain, “39 states did not have enough money to pay all of their bills,” including Texas. Truth in Accounting asserts that this problem will only get more severe when “the states face varying and unpredictable effects from the global pandemic.” Truth in Accounting divides state debt “by the number of state taxpayers to come up with the Taxpayer Burden.” By this logic, when it’s finally time to reckon with the coronavirus-induced recession, you, the taxpayer, will be directly responsible for fixing financial mismanagement.

I’m quoting heavily because I want to make sure that I’m not mischaracterizing how ham-handed both this method and line of thinking truly are. Truth in Accounting follows a simple demonization path: many states are in debt; that debt is caused in part by unfunded pension liabilities; public employees and their pensions are directly responsible for the severity of the post-COVID economy; taxpayers need to stand up for their own money being used in such a fashion.

We will see the relevance of Texas in a little bit.

From last week: WHY TRUTH IN ACCOUNTING’S RECENT CLAIMS ABOUT PENSIONS ARE INACCURATE

TIA often argues that taxpayers are responsible for paying their city and/or state’s unfunded liabilities in a few ways. First, if a pension isn’t at 100% funded status in the course of a given year, they state that the pension is somehow in grave jeopardy and that its unfunded liabilities need to be paid immediately to ensure the pension is “debt-free.” They then calculate a supposed “taxpayer burden,” or an amount each taxpayer will have to pay to meet their state or local pension’s unfunded liabilities.

These tactics, which are often amplified by news outlets critical of public pensions such as the Center Square, are designed to elicit fear that taxpayers will have to fork over a large bill at some point in the future for their area’s pensions.

Okay, so the first main point of NPPC is that TIA is misleading with their balance sheet measure, to be a method for attacking public pensions.

For the most recent NPPC post I linked, they’re reacting to a TIA report on just 10 cities. (as opposed to their bigger Financial State of the States report). Let’s look at what TIA wrote about that and see if they’re emphasizing the public pension burden…. or if they’re doing something else.

State of the Cities, 2021

TIA’s most recent State of the Cities: City Combined Taxpayer Burden™ Report

Truth in Accounting has released a new analysis of the 10 most populous U.S. cities that includes their largest underlying government units.

With the exception of New York City, most municipalities do not include in their annual financial reports the finances of large, underlying government units for which city taxpayers are also responsible, such as school districts, and transit and housing authorities.

At least NYC gets something right.

Here is a ranking of the combined Taxpayer Burden for taxpayers living in the 10 largest cities (from best to worst):

1. Phoenix (-$10,400)

2. San Antonio (-$19,200)

3. Houston (-$24,400)

4. Dallas (-$26,000)

5. San Diego (-$34,100)

6. San Jose (-$41,800)

7. Philadelphia (-$45,300)

8. Los Angeles (-$47,600)

9. New York City (-$85,400)

10. Chicago (-$126,600)

To note: this is the per taxpayer amount.

Again, they’re taking a snapshot of the net asset/liability stand. There’s nothing in their introductory text that privileges any sort of government debt, though they note they remove all capital assets/liabilities (such as building a new bridge, and issuing a bond to build that bridge).

For each governmental unit, on the liability side they report:

1. Unfunded pensions benefits due

2. Unfunded other post-employment benefits (usually mostly retiree health care)

3. Other bills (non-capital-related bonds, mainly)

So yes, pension liabliities (and OPEBs – other post-employment benefits) are reported, but they are not given any special place compared to “Other bills” which is not pension= or retiree benefit-related.

Let us look at the report itself, and see if they emphasize how huge the public pension obligation is. [I would, but I’m not TIA]

I’ve decided to pick on NYC, because it’s local to me and it’s the simplest of their cities in the report.

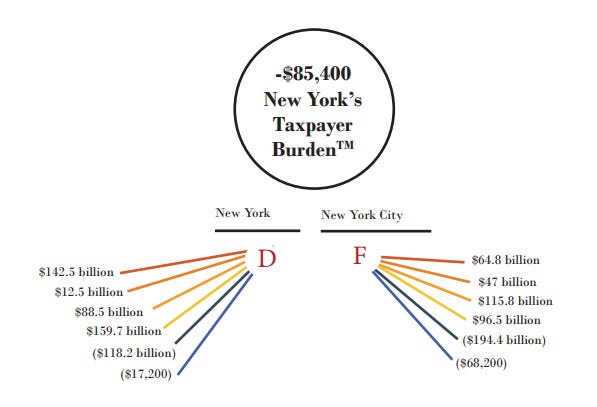

New York City taxpayer burden: $85,400

This is what it looks like for NYC:

Just two parts: city and state obligations. Ah, so simple.

And it makes it very easy for me to aggregate in a graph, which, note, TIA did NOT do. (but I’m doing). For each city in the report, they will give the per-taxpayer burden by entity, but they don’t aggregate by source of obligation.

But I will.

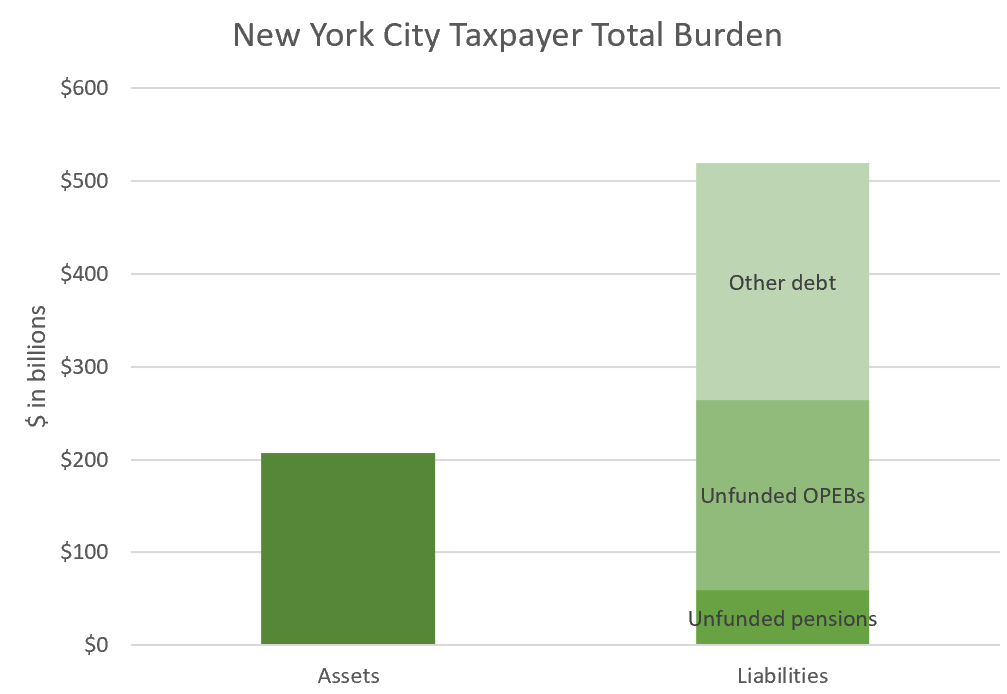

TIA could have done what I just did, if the point of their exercise was to emphasize how much of this city-taxpayer-burden came from pensions and other retirement benefits for public employees. They have the numbers. All they have to do is add.

And according to these numbers, the unfunded pension liabilities for NYC taxpayers aren’t a huge portion of that taxpayer burden (at least on a percentage basis). A lot of the burden is coming from OPEBs (probably retiree healthcare) and from other debt (likely bonds).

From a taxpayer point of view, the people who will be asked to fund not only the pensions, but also pay for the OPEBs and pay off the bonds, it doesn’t much matter the mix of the debt. Yes, for some of the cities, the unfunded pensions are their worst debt. But we’ve seen for NYC, the primary component isn’t pensions.

Do you think taxpayers care about this breakout? TIA doesn’t seem to think so, because they break out taxpayer burden by entity, as with Chicago:

Notice they only care about the governmental level/entity, not whether it was pensions or bonding. And I don’t think taxpayers will make much of a distinction, either.

It has nothing to do with blame. It has everything to do with “Can we afford this?”

With respect to fear-mongering, TIA ain’t mongering much. They don’t even emphasize pensions over other debts. The numbers just fall where they do… and TIA isn’t even doing what I would do if I wanted to put the PUBLIC FINANCE FEAR into people looking at the taxpayer burden.

You wanna see something scary? A more realistic pension debt number would do it

If I really wanted to scare taxpayers, and, more importantly, scare public employees and retirees, I would use estimates of the unfunded pension liabilities more like what the major credit rating agencies use.

Example, from December 2017: How Do Public Pension Plans Impact Credit Ratings?: [edited for readability]

The current state is captured across agencies as a net pension liability measurement at a snapshot in time. A key difference in the current state metric used across the agencies is the adjustment to the state or local government reported liability. This is an important point, as some of the adjustments made have a significant impact on the net pension liabilities that the credit rating agencies consider, as opposed to what is reported on the entity’s balance sheet and/or used for planning and budgeting purposes.

At one end of the spectrum is the adjustment Moody’s makes to the net pension liability. The metric that is incorporated into the credit rating is adjusted to use a market discount rate (currently, 3%–4%), similar to the pension liability measures reported in corporate sector financial statements.

By contrast, the median discount rate used by public plan sponsors in determining their funding contribution is 7.5%, reflecting the expected long-term rate of return on assets, and resulting in a much lower reported liability. For example, for a pension plan with a 12-year liability duration, a 1% decrease in the discount rate would result in a 12% increase to the plan liability.

Fitch also uses an adjusted net pension liability figure, using a static 6.0% discount rate for liabilities that are calculated at a higher discount level by the plan sponsor. These adjustments highlight the agencies’ focus on the potential economic impact unfunded pension obligations may have on a state or local government’s financial stability, as well as allow for easier comparison across entities.

The credit rating agencies may have changed their approaches since December 2017 (I haven’t checked), but the point is that some of them would calculate a much higher pension debt than governments officially report. I know I would.

[Eugene Fama said:] “What’s the risk-free real rate? Is it anywhere near 7.5 percent? It isn’t. Historically, it’s like 2 percent. A 2 percent discount rate would approximately triple Illinois’s pension liabilities.”

TIA isn’t using an adjustment of the pension liability numbers. TIA is using the numbers as reported by the government entities.

TIA is not doing anything fancier than taking numbers already in the financial statements and aggregating so that taxpayers can see all of the government financial burdens they need to think about for long-term decision-making.

Like deciding whether to move somewhere else.

TIA has never claimed that the debts are immediately payable. They aren’t even over-emphasizing the public pensions, which they could do. They are saying there are long-term (and some short-term) consequences of having a large debt overhang.

Missions of the two organizations

I want to note the explicitly stated goals of both NPPC and TIA.

The NPPC’s about us page:

NPPC believes every American should be able to retire with dignity. Across the country, millions of public employees rely on their defined benefit pensions to ensure they can retire with security. It is NPPC’s mission to protect and advance the benefits of America’s hard-working public employees who deliver the services our communities rely on.

We know that there is no one more interested in strengthening the public pensions system than the public employees who are counting on pensions to retire. After all, public pensions are the only source of retirement for 30% of public employees since they do not receive Social Security.

Founded in 2007, NPPC remains a leading voice on the importance of defined benefit plans. Working with a network of national and state-based organizations, NPPC continues its mission to educate policymakers and the general public on the impact of pensions, not just for the public worker, but for the community and economy at large.

I bolded the key sentence: to protect and advance public employee and retiree benefits

I agree with that mission, but I believe some of their current methods in attaining that goal are not really helpful. For instance, supporting the concept that it’s just fine to underfund public pensions. I will come back to that.

Here is something equivalent for TIA:

What is “TIA”?

TIA stands for Truth in Accounting™, the organization that operates this website. TIA was founded in 2002 to “compel governments to produce financial reports that are understandable, reliable, transparent and correct.” It is a nonpartisan, non-profit organization headquartered in Chicago, Illinois.

There is nothing that would inherently make these organizations oppose each other, based on their stated goals.

Government financial reports that are understandable, reliable, transparent, and correct would be a boon to public employees and retirees as well as taxpayers.

(Forget about bond buyers. They should look out for themselves.)

I would argue that highlighting how much public pensions are underfunded is a help to public employees and retirees, to make them clamor for more full funding of their pensions.

Texas: middle-of-the-pack, low-cost, and making up their own definitions of actuarial soundness

I said I would get back to Texas, so let’s see what the relevance Texas had in the October 2020 post.

It’s because the post was written by Keegan Shepherd, Policy Coordinator for the Texas Pension Coalition.

Shepherd is writing from the point of view of the various Texas public pensions, most of which look more like the entire country’s DB public pensions in terms of a slowly decreasing funded ratio… but unlike most public pensions, they’ve actually managed to keep their required contributions from escalating the way they have elsewhere:

It’s increasing, just not as rapidly. Yay, Texas!

Let’s see what Shepherd has to write about their state:

In reality, that’s not how pensions work. Pension math is simple––even when accounting for debt. By our own state law, a pension is actuarially sound when it has an amortization period below 31 years. In other words, pension debt in Texas is considered healthy if it can be paid off through investment returns and contributions within a 31-year period. Anything above that should require action, either from the legislature itself or from our Pension Review Board.

Oh.

OH LORD. I REMEMBER THIS.

October 2020 I wrote: A Fisking of Yet Another Public Pension “Explainer” and a Closer Look at Texas ERS

Don’t mess with Texas, Truth in Accounting! Take that!

There are various things in this piece… some of which are entirely true, and some of which made me stop in my tracks.

….

“By our own state law, a pension is actuarially sound when it has an amortization period below 31 years.”

…..

Well, you can define it as actuarially sound that way, but it doesn’t make a pension benefit design or funding plan sustainable.

……

The term “actuarially sound” has been controversial within the actuarial profession itself over multiple fields, not just pensions. Here is a report from 2012, from the American Academy of Actuaries, detailing how the term is (or isn’t) used in a variety of contexts.

And I continued to rant for a bit. You can read it here.

But Shepherd did have a good point:

When unfunded liabilities do continue to grow, it’s legislators’ responsibility to act early. In the case of our Employees Retirement System, the unfunded liability is the size it is precisely because legislators refused to act early to restore the system to full health. This has only made the problem more expensive to fix, and unless they act during the next legislative session, that unfunded liability will only continue to grow.

In many ways, TIA and NPPC have similar goals: they both know that a large unfunded pension liability is not good.

TIA usually takes the point of view of the taxpayer. NPPC is championing public employees and retirees.

They are not necessarily in conflict…. especially when the taxpayer can leave. There is a reason I emphasize this.

How to protect public sector employees and retirees

You want to protect the benefits of public employees and retirees?

Demand that their benefits be fully funded. And the official financial statements help you see the trajectory for that.

It does not protect the benefits of public employees and retirees to ignore the financial information the states and cities are reporting themselves. The measures in TIA’s reports give an indication of how much has already been promised, but not funded, whether it’s bonded debt or unfunded pension liabilities.

Over-stressed governments rarely get that way rapidly; it took decades for the debt load to grow to the levels we see for the worst offenders of over-indebtedness.

One bit I haven’t quoted in the recent post was where NPPC pointed to modeling showing underfunded pensions being sustainable indefinitely. Here it is:

In their paper for Brookings, authors Jamie Lenney, Byron Lutz, Finn Schüle, and Louise Sheiner note that the assumption that a fund needs to be at a 100% funded status to be fiscally healthy is just that: an assumption that does not stand up to scrutiny.

“People are used to thinking that the government’s budget is like their household budget and that state and local governments are not supposed to have debt,” Sheiner said in an interview with Market Watch. Sheiner is correct that unfunded liabilities are structured a little differently than one’s personal monthly budget.

TIA makes unfunded liabilities seem more ominous than they are because they selectively highlight a pension’s unfunded liabilities in just one year while failing to disclose that pensions specifically invest in the long-term. An unfunded liability simply means that a fund does not have enough assets to pay out retirement benefits to all current and retired public employees. A pension system has never needed all of that money at once. For a current employee who will work for another 20-30 years, the system will have the same amount of time to earn investment returns to distribute pension benefits when that worker inevitably retires. The Brookings report also states “that being able to pay benefits in perpetuity doesn’t require full funding,” so long as policymakers continue making their required contributions.

The TIA folks understand this extremely well. The underfunded pension liability is only for the bit already earned, and has assumptions about what future investments will yield (which I consider overly optimistic and the TIA folks don’t even adjust for).

My main point about the Brookings crew and their “You never have to fully fund!” projections: it’s extremely fragile.

It’s contingent on a bunch of assumptions that are highly suspect. Such as the assumption that GDP will continue to grow in the face of demographic decline.

Another assumption is that the initial indebtedness of the government involved is not too deep. Picking a target less than full funding is fragile to future tax base erosion, which has been seen in Detroit, Illinois, and Puerto Rico.

Yes, I’ve written about this before: Are Public Pensions in a Crisis? Part 2: Is Pay-as-You-Go Sustainable?

PAY-AS-YOU-GO IS FUNDAMENTALLY UNSTABLE

Heck, public pensions used to all be pay-as-they-went, and given the trouble various public pensions ran into in the 1930s, they realized they needed to pre-fund the pensions.

….

There are two aspects: the tax base has to keep growing or the pension benefits have got to quit growing so rapidly for pay-as-you-go to be stable.What if you’re Detroit? Or Illinois? Or Chicago?

Or Rhode Island. Or Puerto Rico. Or California…. and I keep going on.

Many of the worst public pensions for fundedness are that way not only due to deliberate underfunding on the part of the sponsors, but also because the tax base was never big enough to fulfill the promises being made. That is the point of the snapshot being made in the TIA reports.

It’s not that it has to all be paid now. It’s considering that this is the value of the promises made in the past using very optimistic valuation assumptions to value pension debt and it’s right now too high to pay off for the tax base you already have. If you have a shrinking tax base, such as with Detroit, it’s even worse.

The NPPC would better protect and advance the benefits of public employees and retirees by advocating targeting full funding for public pensions. Yes, that would be accomplished over time, and not all in one year. That’s how balance sheets and long-term debt work.

Perhaps the NPPC would like to educate its own members on what truly makes their pension promises reliable or fragile, and it’s not the people who simply aggregate financial statements.

The NPPC has been focused on trying to prevent traditional defined benefit pensions for public employees being converted over to defined contribution or hybrid plans. I don’t have an issue with that, but their strategy seems ill-suited for the goal. The NPPC really need to think about their most vulnerable members. Complaining that TIA is showing which are the most fiscally-stressed places is not going to protect the public employees or retirees. TIA is simply using governments’ own financial statements to show this.

It’s not TIA making public pensions more fragile. It’s the stubbornness not to even take the message of the governments’ own numbers into account: Public Pension Watch: The Fragility of “Can’t Fail” Thinking

What actually threatens the actuarial soundness of public pension plans is behavior like the following:

Not making full contributions.

Investing in insane assets so that you can try to reach target yield. Or even sane assets that have high volatility to try to get high return, forgetting that there are some low volatility liabilities that need to be met.

Boosting benefits when the fund is flush, and always ratcheting benefits upward.…..

Because they thought that pensions could not fail in reality, that gave them incentives to do all sorts of things that actually made the pensions more likely to fail. Because, after all, the taxpayer could always be soaked to make up any losses from insane behavior.

….

If the employee unions in Illinois knew that it was possible that they might actually only get 40% of what was promised, they might not have been so blasé about the undercontributions. They might have asked for more realistic investment targets.The explicit ability to renege on pensions (known by all parties) would make them less likely to fail, because employee unions would then have some incentive to make sure pension contributions are made, and they would be less likely to ask for benefits that may make their pension plan insolvent. If they knew that no, the taxpayer wouldn’t be there to bail them out of stupid investment decisions, they might not be so happy with all the opaque investments.

This is not about scaring the taxpayer. Taxpayers have already rethought where they’re living over this past year, with many people fleeing places like Illinois and New York City.

This is about informing people, which includes informing public pension participants, both the not-yet-retired and currently retired.

NPPC, I recommend you think through what will actually inform and protect your members. The TIA folks are not distorting the message, except to the extent that state and local governments are undervaluing their pension and OPEB promises.

Complaining about TIA will not make the pensions better-funded. Complaining about TIA will not prevent the worst-funded pensions from running out of assets, which will not be supportable as pay-as-you-go, as the asset death spiral before that will show that the cash flows were unaffordable for the local tax base.

And don’t look to the federal government to save your hash. So far bailout amounts have been puny compared to the size of the promises.

TIA didn’t start the fire

As I said to someone else about a stressed public pension, don’t blame me for the huge pile of shit I just pointed out to you. I didn’t create the pile. I just pointed at it. And I didn’t have to do much — officials also communicated to me that stinking pile. I’m just interpreting the mystic language into something other people can understand.

So NPPC, I highly recommend you focus on the pensions running out of money, like in Chicago. TIA is giving you (and public employees and retirees) useful information by aggregating these results. It tells you where the most acute trouble is.

This is not about blame, but about information. If you, NPPC, don’t want to use that information to help and educate your own constituent groups…. well.

What was your mission, again?