Multiemployer Pensions: Prior Bailout Plan's Shortcomings and State of Play

In November 2019, I looked at a press release announcing a proposed reform/bailout for multiemployer pensions. It addresses multiple problems with MEPs, some of which have been entirely ignored in the other major MEP bailout proposal out there, specifically, the Butch-Lewis Act.

Well, Congress seemed to have gotten itself snarled up in a bunch of time-wasting crap (and unfortunately, a key staffer died in January), but I need to revisit this, even if Congress doesn’t prioritize this over the presidential-campaign-and-Congressional-campaign positioning this year.

Because some extremely key pensions will run out of cash, and the PBGC will be brought to cash insolvency (finally), unless Congress acts in the next couple years.

The Butch-Lewis Act (a version which passed the House in 2019: H.R.397 – Rehabilitation for Multiemployer Pensions Act of 2019) has been trotted out a few times as a proposed fix for failing multiemployer plans, and not too much about the non-failing plans.

Let’s look at that one before I get to the newer proposal to bailout MEPs.

ANALYSIS OF BUTCH LEWIS BAILOUT, THE PRIOR PROPOSAL

My prior posts on MEP bailouts:

December 2017: Rumors of Pension Bailouts: MEPs and Public Pensions

November 2018: Multiemployer Pensions: Waiting for the Bailout Report

February 2018: MEP Watch: About Those Plans to Bail Out Union Pensions

November 2018: MEP Bailout Quickie: Collapses Like a Flan in a Cupboard

From that last post, I linked to a study by The Pensions Analytics Group. Their key finding re: the Butch-Lewis Act:

Our findings suggest that the Butch Lewis Act would not be an effective mechanism for preventing plan insolvencies. In general, a loan would delay a weak plan’s insolvency, but not prevent it. Eventually, taxpayers and the PBGC will be called upon to deal with insolvency costs in the form of loan defaults and PBGC assistance payments.

Now, of course, they have a newer paper dated November 2019 looking into a variety of options for bailouts Here is a key finding:

Using the Multiemployer Pension Simulation Model (MEPSIM) we project that, absent significant remedial action, about 160 multiemployer pension plans covering over two million participants will become insolvent by

2040. We also project that the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation’s (PBGC) multiemployer guarantee fund — the backstop against such insolvencies — will itself be exhausted by 2027. This constitutes a systemic failure for the PBGC, the bankrupt plans, and the participants and retirees in those plans.

So, 2027 may not seem too close, but there can be trouble even earlier than that. It’s a matter of when the Central States Teamsters plan, specifically, goes bust officially.

Here is another key result:

In an effort to mitigate this crisis, the House of Representatives recently passed the Rehabilitation for

Multiemployer Pensions Act (RMPA), also known as the Butch Lewis Act. If passed by the Senate, this would

provide troubled multiemployer pension plans with low interest rate loans funded by the federal government.

Using MEPSIM, we determined that RMPA will not alter the downward trajectory of most struggling multiemployer plans because it doesn’t address plans’ underlying funding deficits. Rather, it would temporarily mask the deficits rather than reduce them. Despite the loans, many troubled plans would still become insolvent, and those insolvencies would exhaust the PBGC’s multiemployer guarantee fund. In addition, the federal government could potentially be saddled with tens of billions of dollars of unpaid loans.

The main problem is that Butch Lewis is a half-assed bailout, only temporarily fixing holes, pretending that it’s not a bailout at all (because they’re “loaning” the money…which has no way of being clawed back when it all goes out into benefits), and would require additional bailouts years down the road. Which are not being guaranteed right now.

I am not going to address their [Pension Analytics’] proposed reforms, because I would rather look at actual proposed plans as opposed to what we think is ideal. Also, you can read their paper yourself.

That said, Butch-Lewis is a serious proposal inasmuch it has been voted by the Democratic House.

RECENT CHOICES FOR DEALING WITH BANKRUPT PLANS

Before the most recent proposal, from Senate Republicans, there have been two choices on offer:

1. Do nothing, let Central States (a hyuuuge MEP, in very politically important states) go bust in a few years taking down the PBGC with it, some much smaller MEPs also go bust, and oh well. Lots of pensions are going bust. Whaddya going to do. (default choice)

2. A half-assed bailout that would put off the reckoning for Central States and some of the other politically key MEPs by a decade or two (if they’re lucky), and then let it play out again when the half-assed bailout’s money is used up. (Butch Lewis)

Obviously, there are lots of potential approaches to dealing with MEPs, and one item I didn’t mention was the few dozen applying for benefit cuts before they hit rock-bottom. (This one is easier to read, but it’s not official.)

The problem is that some of the plans can’t qualify for those cuts, because they need cuts deeper than allowed by the law in order to be sustainable. They do need a bailout just to support a situation with deep benefit cuts.

NUTSHELL PROBLEM WITH FAILING MULTIEMPLOYER PLANS

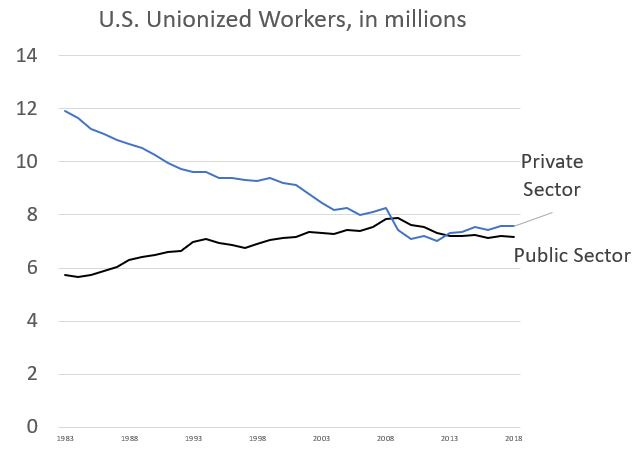

The biggest problem for MEPs: shrinking private union rolls.

From a prior post on union membership, you can see this is the private unionization trend:

There’s a reason I looked at the absolute numbers, and not the percentage of workers (though it is in single-digit percentages for private-sector workers now). A 37% decrease over the period shown is a substantial drop.

The reasons for this drop can also feed into potential solutions — perhaps there can be new growth, or perhaps the private sector unions will dwindle even further.

But it doesn’t even take shrinking — it just takes not growing as fast as assumed, with payrolls not growing as fast as assumed, and contributions ultimately not growing as fast as needed to fund the pension, or just to keep it going.

Some of the union pensions that have been in trouble have really lopsided demographics. I will grab one of John Bury’s posts — he has been keeping a good record of the plans that have applied for reducing MEP benefits.

Here is one of his reports from July 2019, on the filing of two plans. They are teeny plans, but look at the numbers:

Plan Name: IBEW Local Union 237 Pension Fund

EIN/PN: 16-6094914/001

Total participants @ 12/31/17: 399 including:

Retirees: 169

Separated but entitled to benefits: 60

Still working: 170

….

Funded ratio: 16.18%

Plan Name: Composition Roofers Local 42 Pension Plan

EIN/PN: 31-6127285/001

Total participants @ 12/31/17: 485 including:

Retirees: 235

Separated but entitled to benefits: 77

Still working: 173

…..

Funded ratio: 32.99%

In both cases, the plans are grossly underfunded, and the number of “active” members – that is, working and thus have pension contributions being made – are well less than 50% of total participants.

In the case of the roofers’ plan, almost 50% of the participants were retirees.

This is not a demographic ratio that makes it feasible to climb out of the funding hole.

What if a union has no active members to contribute to the fund? How is that supposed to work?

And why should current union members be on the total hook to pay for the retirement of people who may have retired decades before they themselves started working?

DESERVE HAS GOT NOTHING TO DO WITH IT

Continuing on in this line, I want to pull out a particular comment, in which people reacted to some of what Elizabeth Bauer wrote with respect to the MEP bailout proposal back in November 2019:Bailouts, Benefit Cuts, Taxpayers And Promises: From The Mailbag

But Charlotte says, with respect to the Multiemployer Plan Reform Act and the ability it gives plans to cut benefits to stay solvent,

“I think you are saying I didn’t deserve the money I was promised by my company when I retired. Is it, therefore, fair to assume the mortgage I agreed to pay for 20+ years should be null and void because since I didn’t get my retirement money, I have no money to pay the mortgage? The agreement I signed means nothing because my circumstances have changed or, does this only apply to corporations when making agreements with employees?”

Some people are confusing “deserve” and “what you’re going to get, even if you deserve better.”

What I mean by that is that often when I (or Elizabeth) write about what will happen (or is highly probable to happen) if certain choices are made, people confuse it for us saying that’s what should happen.

I know people are used to the “should” aspect in too much of the writing on pension reform, but most of the “should” I write about is the communication of what trade-offs are involved in various choices.

For example, the politicians should just use the word “bailout”, because using various wording about “loans” or “limited transfer of federal taxpayer funds” isn’t fooling anybody. Yes, I know they’re trying to frame the debate, but no matter what technical phraseology is used, regular people will say “bailout”, as that’s what this is about. So stop trying to avoid it.

But let us address Charlotte’s comment above. If an individual’s pension money isn’t there, and they are unable to pay the mortgage, what happens is… they don’t pay the mortgage. And the bank forecloses on them, forces a sale of the property, and tries to claw back from the loss.

The bank has made sure the promise made in a mortgage is backed by real estate (they could be wrong about that real estate’s value, but it still exists). The house and land are assets the bank can take possession of when payments aren’t made. The bank can recover some of their loss, and may even be made whole under a foreclosure situation.

Unfortunately for participants in bankrupt multiemployer pension plans (bankrupt meaning the assets have run out), there is no asset backing the promise, other than the PBGC guarantee [and that amount is set]. If the pension plan breaks their promise because the money has run out, there is nothing pension participants can grab.

This is not a matter of what should happen or what the pension participants deserve. It’s a matter of what does happen.

The PBGC gives drastically reduced benefits for MEPs once the plan has officially gone bust. The guarantees for single-employer plans are higher. If you were in a church plan or public pension plan, you can actually end up with nothing, as these aren’t covered by the PBGC.

I will agree that people deserve what they were promised. But that doesn’t mean they’ll actually get it.

WHEN PROPOSING A BAILOUT, THINK ABOUT WHO WILL BE PAYING FOR IT

Yes, there are a lot of people to blame for the MEP plans going bust, including actuaries assuming that there will be more and more people in the future to contribute to the plans. Unfortunately, many of the people to blame for not setting up a sustainable pension plan are usually long gone by the time the plan goes bust. In any case, even if those to blame are still around, they probably don’t have enough money to make the pensions whole.

So we’re left asking other people, those who didn’t make the pension promise, to give the failed plans some money. Talking “deserve” is all very well, but the people who can make the pension whole weren’t the people who made the promise. The people who made no promises and are being asked to pony up will wonder what they themselves deserve in this situation if one starts talking about “deserve”.

This is the whole point of these bailouts. Pretending they’re not bailouts is silly. Everybody knows they’re bailouts….if they are to work.

But people who are doing the bailout would like to know they’re getting something for what is being asked.

COMPARISON TO BANK BAILOUT

I think it’s entirely reasonable to ask about prior government bailouts — how did the 2008/2009 bailouts work?

Before going down the specific numbers, I need to remind people that the bank bailouts were not all that popular. At the very least, the bailouts led to the Dodd-Frank bill in 2010. Yes, the bailouts were popular among people in the finance sector (well, the counterparties who were made whole, at least), but in general, whether Tea Party or #Resistance, they were seen as shady.

So arguing “Give us a bailout because of this other, politically unpopular, bailout” is probably not the framing desired by people who want a pension bailout.

So let’s look at the bank bailout — Troubled Asset Relief Program:

The Troubled Asset Relief Program was a $700 billion government bailout. On October 3, 2008, Congress authorized it through the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. It was designed to keep the nation’s banks operating during the 2008 financial crisis. To pay for it, Congress raised the debt ceiling to $11.315 trillion. TARP expired on October 3, 2010.

…..

Why TARP Didn’t Cost Taxpayers

As of 2018, TARP didn’t cost the taxpayers anything. Instead, Treasury received $3 billion more than the $439.6 billion it disbursed. Of that, $376.4 billion was repaid by the banks, auto companies, and AIG. The U.S. Treasury made a profit of $66.2 billion on those because it bought shares of the banks when prices were low and sold them when prices were high. Treasury made $5 billion on its TARP fund investment in AIG. The programs targeted to help homeowners allocated $37.4 billion. As of September 2018, they spent $27.9 billion. Those funds were never meant to be repaid.

You may want to read the whole thing. I have my own opinion on this, which I don’t care to get into right now. Here’s the wikipedia article on it.

The issue is that the bank bailout always did have the potential to have the funds paid back… and they were [nominally] paid back. There were plenty of people who lost their equity value in various companies, and who did not get any direct benefit.

What about the MEP bailouts? At least the new proposal, MARP, is not pretending that bailout money would get paid back. But Butch-Lewis talks about low-interest rate “loans” to top up pension funds… and this is just an awful thing. There is no mechanism, other than leverage (aka doubling down), for which these plans will be able to repay the loans. Please, just straight bail out the pension funds.

One thing Americans especially hate is being taken for suckers. We know the pensions require a bailout if people are not to get deep benefit cuts. Just call it a bailout, do a real bailout, and move on.

BLAME GAME CAN HELP IF IT PREVENTS SAME MISTAKES

A big part of the political framing of this issue is to find people to blame. But I’m not sure this will really get any particular side very far, even though most humans have a difficult time with the concept of sunk costs.

The nature of pensions is that, often, when the plan runs into trouble, the people who made the decisions that ultimately caused the failure are long retired themselves (or dead). These plans rarely fail out of nowhere, and it is generally a work of decades to get to failure. Even if the people to blame are still around, they’re very unlikely to have enough money to make the pensions whole.

One thing for sure – the people being asked to provide the bailout as a group – aka federal taxpayers and even current MEP active participants – have no responsibility for multiemployer plan failure. And they know they had nothing to do with it.

Solutions are going to require compromises: I think you can get the general federal taxpayer to agree that the MEP guarantees are way too deep as pension cuts, but, as they’re not the ones who made the pension promises, why should they be on the hook for 100%?

This is how Elizabeth Bauer addressed the problem:

Folks, there are no easy answers. That I urge reform of Chicago’s or Illinois’ pensions due to their severe underfunding and the unsustainably high contribution levels needed just to get to some semblance of funding several decades in the future, does not mean that it is a pleasant thing for retirees to have pensions cut, or for workers to lose benefits they were counting on accruing in the future. And likewise, to what extent the government’s promise to multiemployer pensions extends, in some way morally speaking, beyond what’s written in the letter of the ERISA legislation, is not a simple question because of the many workers who depend on these benefits.

It does suck when you don’t get what you were promised. In some of these cases, what was promised was way too high. In some cases, the promises were okay, but the assumptions for funding were way off (especially the “we’ll pay more later”.)

What I want is a solution that will do better than temporarily push off the problem, assuming it will be easier/better to address it in a decade, rather than now.

For these types of problems, addressing them sooner is almost always better than pushing it off til later. That’s how these plans got in trouble in the first place.

Butch-Lewis is nothing more than a temporary fix, which will require going back to the well in a decade or so. I understand many politicians would rather that situation, because a problem permanently fixed is not one they can use for much political leverage.

A problem that bubbles up every ten years or so provides all sorts of political possibilities.

In my next post, I’ll look at what other people have had to say about the Republican proposal.