Mortality with Meep: U.S. Excess Deaths Related to Covid Update to August 27, 2020

also, data people: GET SOME STANDARDS

I have loads of COVID-related mortality to lay on y’all, and no, I’m not doing a video (yet). It is much faster for me to write an extremely long post than to get a video together.

So a post it is.

The current shape of mortality in the United States

Here is an update of my mortality spreadsheet, using CDC data which can be found here. I have not grabbed all data sets, because I find some more useful (and reliable) than others.

My own figuring of excess deaths for the U.S. through 25 July 2020 (yes, there are data through the week ending 15 August 2020, but the last couple weeks are very incomplete, and I don’t like their “weighted” results).

So, there was a first wave of COVID mortality, which peaked in mid-April, and there was a second wave (hitting places like Florida and Arizona) which seems to have peaked at the end of July.

Here is an animated gif so you can see where mortality peaked and when:

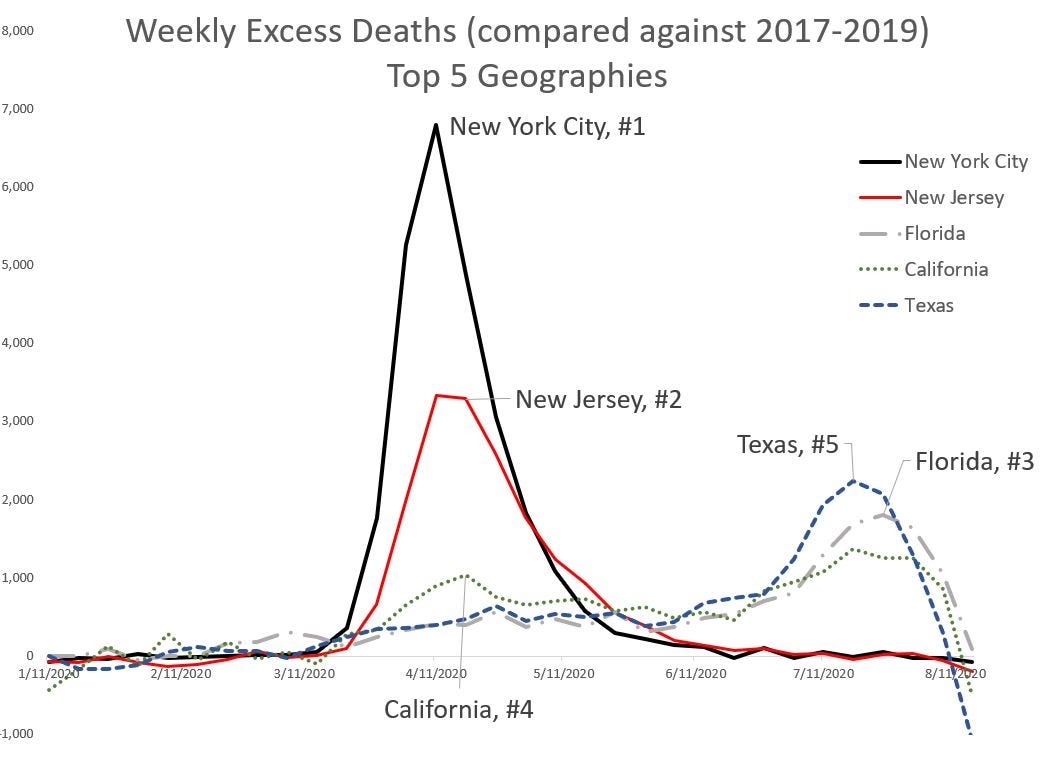

To be nasty, I’m going to take the top 5 geographies in this set by total excess deaths:

Now, Florida, Texas, and California being top places where there are deaths? Those are top 3 states by population. That they are ranking in the top 5 for total excess deaths isn’t much of a shock. That New York City by itself, at about 8.4 million people, would rank at about #13, and New Jersey, at #11… well they’re the top two for total deaths.

Let’s do a more fair comparison — let’s look at the cumulative excess mortality, and get the top 5 geographies:

No surprise, both NYC and New Jersey are still the top 2. But then DC comes in as #3, at no surprise to me. And New York state, without NYC, is #4. Finally, Massachusetts is #5. These five geographies were hit hard in that first wave that peaked in April.

What do you know about COVID mortality? Or regular mortality?

This is not (exactly) a criticism of Mark Glennon and the Wirepoints crew. It’s just that I know a lot more about this than they do.

Americans have been “blinded from science,” according to a recent research report about their understanding of COVID-19. And it’s not about the controversial aspects like treatments and lockdown policies. It’s about ignorance of fundamental, undisputed facts on who is at risk.

A leading financial firm, Franklin Templeton, figured that people’s behavioral response to the pandemic will play a crucial role in shaping the economic recovery, so they teamed up with Gallup, the polling outfit, to find out what people know and don’t know.

“These results are nothing short of stunning,” concluded the firm. “Six months into this pandemic, Americans still dramatically misunderstand the risk of dying from COVID-19.”

That’s no exaggeration, and the implications go far beyond the economic behavior Franklin Templeton was interested in.

Here is what they found:

First, the Franklin Templeton-Gallup survey found that the general population has little understanding how heavily the pandemic is focused on the older population. It is not broad-based. From the report:

On average, Americans believe that people aged 55 and older account for just over half of total COVID-19 deaths; the actual figure is 92%.

Americans believe that people aged 44 and younger account for about 30% of total deaths; the actual figure is 2.7%.

Americans overestimate the risk of death from COVID-19 for people aged 24 and younger by a factor of 50; and they think the risk for people aged 65 and older is half of what it actually is (40% vs 80%).

You can read the whole thing over there, but none of this shocked me because:

Do you know what percentage of all deaths are of people aged 55 or older, usually, in the U.S.? Before COVID?

It is fine to go look it up, because I have to look it up, too. I have a very good idea of the mortality rate by age (that is, the probability of death in the next year given your current age), but the percentage of deaths in a certain age range is dependent on that mortality rate and how many people were in that age bucket to begin with. It’s like when I explained to my grandma why she saw more obits for people 20 years younger than her than her own age (I miss my grandma, who died a year after I had that conversation with her. (Beware discussions of death with me.))

Here are the comparable stats.

While 92% of official COVID deaths are of those age 55 and older, in 2017 (the latest year with completed death data), 87% were of people age 55 or older. Five percentage points aren’t much different.

The percentage of deaths of those age 44 and younger in 2017 were 7%. Again, about a four to five percentage point difference with COVID deaths.

Did you know how high the first one was, and how low the second? In just a regular year?

No, you probably didn’t. I am not going to point and laugh at you Nelson-style, because there’s no reason to expect that you would know that. People have a very bad “gut feel” for probabilities about almost everything, and figuring the odds for something you really don’t want to think about is not going to be high on your list of priorities.

Now, COVID is disproportionately hitting the elderly (hey Boomers, I’m including you in the elderly), but it’s not hugely disproportionate. Those under age 45 are not getting their “normal share” of deaths, and those over age 55 are getting a little more than their normal share.

This can be important information for policymaking, inasmuch you need to know who is specifically vulnerable to the disease, at least with regards to mortality. There’s morbidity, which has to do with suffering the disease (and surviving), which can be pretty severe, and it may be that younger folks have it pretty bad from the disease, but because they’re not as medically fragile, they don’t die. But they can have chronic effects.

In any case, don’t feel particularly bad if you don’t have a good grasp of the shape of mortality from COVID. You don’t have a good grasp of the shape of mortality in normal times, unless you’re an actuary/demographer/statistician who deals with this stuff a lot.

I happen to enjoy thinking about mortality patterns, but most people do not. You don’t need to feel bad about it. For all this survey blather, this is telling me something I already knew: people have a really bad feel for their own mortality (and longevity) risks.

Why I use excess deaths for analysis

I know I’ve explained this multiple times before, but I’m going to do this again.

From 8 August 2020, Tommy Christopher at Mediaite: CDC Data Shows 200,700 ‘Excess Deaths’ During Coronavirus Pandemic, Far Eclipsing 160,000 Confirmed Death Count

According to a New York Times analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), there have been 200,700 excess deaths in the United States during the coronavirus pandemic, much higher than the current total of 161,000 confirmed deaths.

This NYT piece was originally posted in May, but they keep updating it. At the time of Tommy Christopher’s piece, they had updated to August 5. I had checked it at the time, and Tommy’s piece accorded with what the NYT reported, and the thing I would fault the NYT estimate for I don’t want to explain right now, especially since the real numbers caught up with them. I currently see the latest update at August 19, but it will likely be updated again. The numbers are obviously higher now, and the NYT analysis is good enough, I think. For all I may disagree with their editorial board the NYT can be pretty solid on quantitative analysis.

Another data point:

Early on in the pandemic, COVID deaths were undercounted, partly because the testing capacity for COVID was inadequate. Even states with the best death-reporting infrastructure had loads of death I consider probable COVID deaths, but they couldn’t capture them. In some cases, they are going back and recategorizing causes of death (NOTE: THIS IS NOT SOME NEFARIOUS CONSPIRACY. They really were undercounting COVID deaths because of difficulty in identifying the cases.)

Other places are falling down on keeping track of COVID deaths, and I doubt it’s due to testing capacity now. I think it’s due to poor death reporting infrastructure. They’ve got bad systems and bad data. In normal years, this is not a big deal, but it’s one of the reasons it takes over a year for the CDC to get good numbers on the numbers of death in a specific calendar year.

I can’t fault them, much. I have seen much worse data situations at insurance companies, and insurance companies can lose money on bad data (unlike governments, where it’s primarily some officials who get embarrassed, but not fired, for this sloppiness). Insurance companies have done investing in better data systems, because the profit motive is powerful, even for mutual and fraternal insurers. It’s not clear to me that governments have, even when it comes to something as important as death (or taxes).

A big lesson for data people: GET SOME STANDARDS

I have been driven nuts this year by poor data practices, even poorer modeling practices, and then decision-making purportedly driven by these two piles of trash. And then because of the big problems with the data and the models, the decision making becomes totally divorced from even fixed data and models.

I don’t want to get too all uppity with my actuarial privilege — in practice, we obviously fall short of perfection — but seriously, data people, it would do you well to look at actuarial standards of practice (ASOPs).

The following is my absolute favorite ASOP: ASOP 23: Data Quality

The ASOP itself is relatively short, and this is what it is about:

This ASOP provides guidance to actuaries when selecting data, performing a review of data, using data, or relying on data supplied by others, in performing actuarial services. The ASOP also applies to actuaries who are selecting or preparing data, or are responsible for the selection or preparation of data, that the actuary believes will be used by other actuaries in performing actuarial services, or when making appropriate disclosures with regard to data quality. Other actuarial standards of practice may contain additional considerations related to data quality that are applicable to particular areas of practice or types of actuarial assignment.

If an actuary prepares data, or is responsible for the preparation of data, to be used by other actuaries in performing actuarial services, the actuary should apply the relevant portions of this standard as though the actuary were planning to use the data, taking into account the preparing actuary’s understanding of the assignment for which the data will be used.

This standard does not apply to the generation of a wholly hypothetical data set.

This standard does not require the actuary to perform an audit of the data.

If the actuary departs from the guidance set forth in this standard in order to comply with applicable law (statutes, regulations, and other legally binding authority), or for any other reason the actuary deems appropriate, the actuary should refer to section 4.

There is nothing about this standard that means it’s useful only for actuaries. All of the parts of the standard can be used by anybody doing important analysis.

Here are some of the practices embedded in this ASOP:

Considerations when you select data for use (again, there is a reason I use total deaths and not official COVID deaths)

What should be involved in a review of data (for example, you need to understand what the data definitions are, such as if there are codes used for categorical data)

How you should deal with defects in the data (no real life dataset is perfect, but that doesn’t mean it’s unusable… but you may need to remove datapoints, or make adjustments)

What information about the data source, and other aspects, should be communicated to those consuming your work product.

Guys, I’m not doing actuarial work here. Not really.

Yes, I’m an actuary, but this is a blog post. This is not an actuarial report to a paying client.

Some kind people have bought me tea, I make piddling money off of Amazon links, and some people pay as a subscription… but the money I’ve made off of STUMP really is of the size I can buy myself a few books and some pounds of tea. I don’t think I’ve even earned as revenue the equivalent of one hour of my time on a consulting job.

So no, I don’t have to follow ASOP 23 for my blog.

And yet I do.

I do follow ASOP 23 when I’m dealing with data in my posts. I tell you where I got the data from, I let you know if I see problems with the data, and I let you know if there are aspects of the data I don’t understand.

I don’t just pull stuff out of my ass and point to my credentials.

ASOP 23 is free to anybody dealing with data, and it is full of great advice.

The way you build up credibility is through practices such as these.

The difference between actuaries ignoring ASOP 23 and other data-using people not following its advice… actuaries can get expelled from the actuarial societies, and their credentials stripped. Poor data practices have been behind actuarial malpractice lawsuits.

I have found, in the long run, that if you want your reputation built up for solid quantitative analysis, you really need to follow standards such as these.

SO.

DO.

IT.

Oh, and thanks to all my kind readers for paying me in the best coin of all: your attention.

[But seriously, if you’re a data person, read ASOP 23.]