Back in 2017, I did a post titled Mortality Monday: Memorial Day and the U.S. Civil War, tracing the origins of the holiday to Decoration Day, which was when people would decorate the graves of the fallen from the U.S. Civil War:

May 30, 1868: By proclamation of General John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic, the first major Memorial Day observance is held to honor those who died “in defense of their country during the late rebellion.” Known to some as “Decoration Day,” mourners honored the Civil War dead by decorating their graves with flowers. On the first Decoration Day, General James Garfield made a speech at Arlington National Cemetery, after which 5,000 participants helped to decorate the graves of the more than 20,000 Civil War soldiers buried in the cemetery.

The 1868 celebration was inspired by local observances that had taken place in various locations in the three years since the end of the Civil War. In fact, several cities claim to be the birthplace of Memorial Day, including Columbus, Mississippi; Macon, Georgia; Richmond, Virginia; Boalsburg, Pennsylvania; and Carbondale, Illinois. In 1966, the federal government, under the direction of President Lyndon B. Johnson, declared Waterloo, New York, the official birthplace of Memorial Day. They chose Waterloo—which had first celebrated the day on May 5, 1866—because the town had made Memorial Day an annual, community-wide event, during which businesses closed and residents decorated the graves of soldiers with flowers and flags.

As I wrote in that older post, though the numbers are only approximate, the number of soldiers who died in that war for the U.S. were the highest, whether absolute or percentage of population, for the U.S. (which isn’t that unusual for a civil war.)

Estimates for U.S. Civil War Dead

Let us focus on Union U.S. Civil War dead for now, with one of the early comprehensive estimates developed in 1889 by Lt. Col. William F. Fox.

William F. Fox, Lt. Col. U. S. V., Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865: A Treatise on the extent and nature of the mortuary losses in the Union regiments, with full and exhaustive statistics compiled from the official records on file in the state military bureaus and at Washington

In the first chapter, he focused on regiments with particularly high casualty rates.

The one regiment, in all the Union Armies, which sustained the greatest loss in battle, during the American Civil War, was the Fifth New Hampshire Infantry.1 It lost 295 men, killed or mortally wounded in action, during its four years of service, from 1861 to 1865. It served in the First Division, Second Corps. This division was commanded, successively, by Generals Richardson, Hancock, Caldwell, Barlow, and Miles; and any regiment that followed the fortunes of these men was sure to find plenty of bloody work cut out for it. The losses of the Fifth New Hampshire occurred entirely in aggressive, hard, stand — up fighting; none of it happened in routs or through blunders. Its loss includes eighteen officers killed, a number far in excess of the usual proportion, and indicates that the men were bravely led. Its percentage of killed is also very large, especially as based on the original enrollment. The exact percentage of the total enrollment cannot be definitely ascertained, as the rolls were loaded down in 1864 with the names of a large number of conscripts and bounty men who never joined the regiment.

There’s always been a data quality problem.

He attempted to aggregate the state-level casualties, both for the Union troops and Confederate troops. He separately compiled naval losses, which were less. He also split out soldier deaths due to disease or accidents, as well as more minor causes.

I will re-aggregate his data and use modern language for groups, but you can check out the original language for yourself in the spreadsheets and links.

Union Civil War deaths by state (and broad cause)

I will stick to the Union Army deaths, mainly because those are the ones he has the best data on.

Killed in battle or mortally wounded in battle

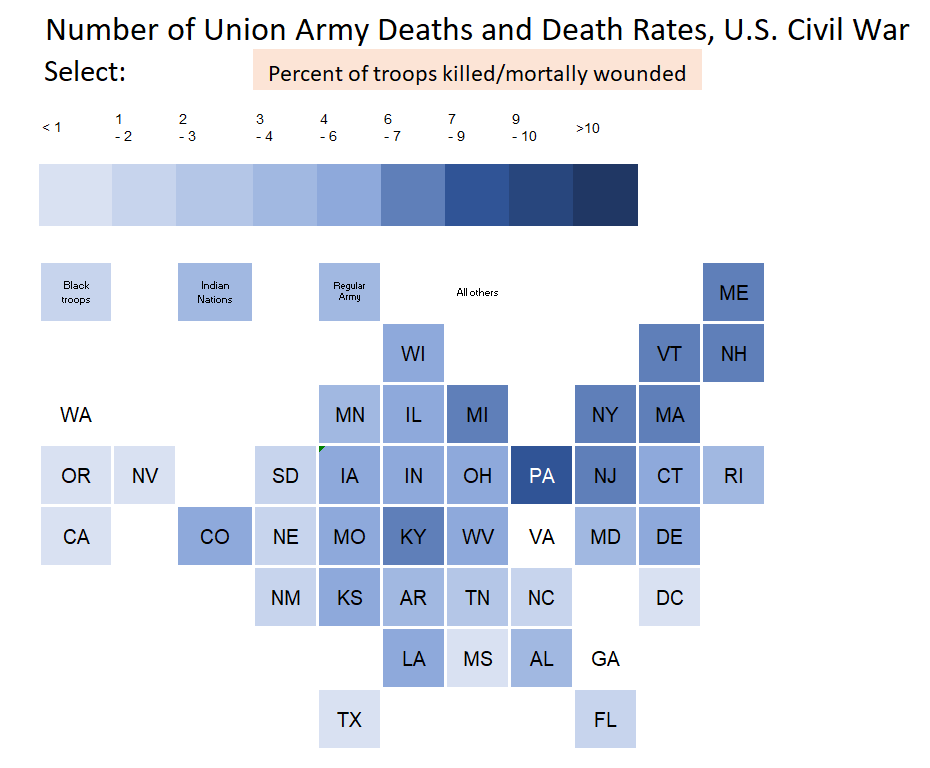

I note that he separated Black troops from the white troops coming from the states, which was fairly easy for him to compile as regiments were segregated in the Union. You will see that some Union troops came from the Confederate states.

The Indian Nations contributing being separated out makes sense, as they were separate entities. The Regular Army was much smaller than the other entities.

“All others” contains much smaller groups, such as the reserves, Hancock’s Corps, U.S. Sharpshooters, and the like.

Here are the rates, as a percentage of the estimated number of enrolled troops.

You can see that the highest rate is among the Pennsylvania troops (some of the white squares are representing missing data from those states — yes, some soldiers came from Georgia and Virginia to join the Union Army.)

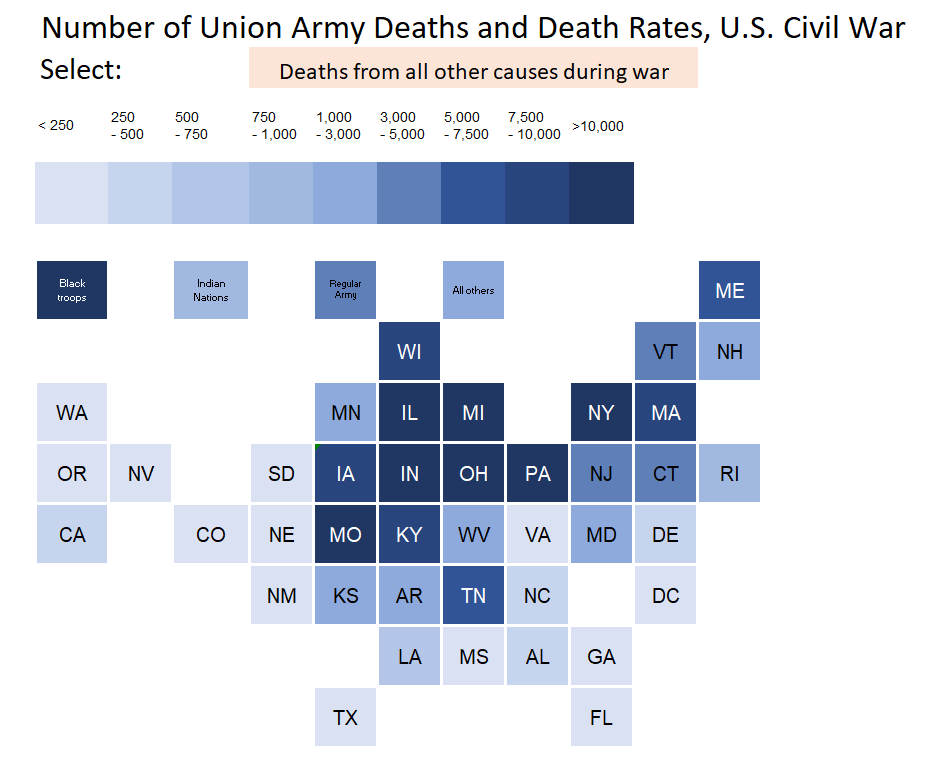

Deaths due to other reasons (mostly disease)

Look at the scale for this one compared to the other one. I will do a separate graph so you can see the difference of deaths from disease, directly from battle, and from other causes.

Let’s look at rates:

This category includes causes of death other than disease, but it is the largest component. There were some accidental deaths, suicides, and murders, as well as some natural causes of death other than disease. But it was primarily disease.

Causes of Death for Union Army

Using William F. Fox’s estimates, here’s how Union Army Deaths break out:

Over half of the deaths were due to disease alone (and that wasn’t including the deaths due to disease in Confederate prisons for Union Army POWs).

An Aside: William F. Fox

From the Wiki page on Fox:

Fox was born in Ballston Spa, New York on January 11, 1840. He graduated from the Engineering Department of Union College in 1860. He fought in the American Civil War as Captain, Major, and Lieutenant Colonel of the 107th New York Volunteers and wrote extensively about his war experiences. His "Chances of Being Hit in Battle" was published by Century Magazine in 1888, In 1889, he published the book Regimental Losses in the American Civil War. He then wrote New York at Gettysburg (three volumes), Slocum and His Men and a biography of General Green.

Fox's family was in the lumber business. He visited Germany to study scientific forestry methods there. From 1875 to 1882, he was a private forester for the Blossburg Coal, Mining and Railroad Company in Bossburg, PA. He became a New York State employee in 1885, as assistant secretary to the Forest Commission. He was an Assistant Forest Warden from 1888 to 1891, and became the first Superintendent of Forests upon the creation of the Adirondack Park.

His reports as Superintendent of Forests were instrumental in the founding of the New York State College of Forestry at Cornell.

My grandfather was a forester in South Carolina. I have to find out more about this Fox.

Especially the “Chances of Being Hit in Battle”… that sounds like the kind of probability exercise I’d be interested in.

Very interesting memorial day reading! Disease is a challenge and perhaps explains the US military's obsession with "vaccines" no matter how remote the odds of coming upon anthrax they insist on a dangerous shot. Not to mention the C-v-19 mess that sidelined a bunch of pilots and caused many separations from service for a questionable benefit from an experimental vax.

Years ago, I saw some statistics regarding the deaths due to disease, infection, or illnesses and they were horrific.