Happy 50th to ERISA!

A key retirement income security law -- that doesn't cover public employees

ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) is almost as old as I am!

ERISA was signed into law on September 2, 1974, spurred by some notorious private pension plan failures.

Studebaker-Packard Pension Failure: 1963

Nevin E. Adams, J.D., January 21, 2021: A Real Life Example [emphasis added]

Born into a wagon-making family, the Studebaker brothers (there were five of them) went from being blacksmiths in the 1850s to making parts for wagons, to making wheelbarrows (that were in great demand during the 1849 Gold Rush) to building wagons used by the Union Army during the Civil War, before turning to making cars (first electric, then gasoline) after the turn of the century. Indeed, they had a good, long run making automobiles that were generally well regarded for their quality and reliability (their finances, not so much) until a combination of factors (including, ironically, pension funding) resulted in the cessation of production at the South Bend plant on Dec. 20, 1963. Shortly thereafter Studebaker terminated its retirement plan for hourly workers, and the plan defaulted on its obligations.

At the time, the plan covered roughly 10,500 workers, 3,600 of whom had already retired and who — despite the stories you sometimes hear about Studebaker — received their full benefits when the plan was terminated. However, some 4,000 workers between the ages of 40 and 59 – didn’t. They only got about 15 cents for each dollar of benefit they had been promised, though the average age of this group of workers was 52 years with an average of 23 years of service (another 2,900 employees, who all had less than 10 years of service, received nothing).

I do not have the details, but given that this was a bankrupt plan, they could only guarantee any of the benefits in 1963 by buying annuities. There was no PBGC (Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation) at the time.

The PBGC was created by ERISA, in 1974.

On September 2, 1974, President Gerald R. Ford signed ERISA into law , which established the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC). "Under this law," President Ford remarked, "the men and women of our labor force will have much more clearly defined rights to pension funds and greater assurances that retirement dollars will be there when they are needed."

More on the PBGC in a bit. More on the Studebaker bankruptcy below:

Studebaker pension plan closure and bankruptcy — “Avoiding Studebaker” by Robert Toth [emphasis added]

I had just completed a fiduciary training session for a client’s board in South Bend, IN, when one of the more senior board members pulled me aside to tell me a story. His father had been employed by Studebaker when it went under in 1963 — and took its pension plan with it. As the story goes, and which I had shared earlier with the board, the financially struggling automaker had borrowed money from its pension fund in order to keep the company afloat. The company did not steal the funds (it was fully obligated to repay the money back to the plan) but it was a transaction in which a “prudent fiduciary” would not have engaged. Indeed, it was only the influence of the corporate officers on the pension board which enabled the transaction.

History tells the rest: the company went belly-up, not only causing the loss of 4,000 jobs, but also their pensions. That board member discussed the horrible consequences suffered by the former employees and the community at the time. It is that bankruptcy, and loss of the pensions, which served as the “policy trigger” which resulted in the passage of ERISA some 10 years later. ERISA would have prevented that disastrous loan which lead to eventual collapse of the retirement plan.

Think about the “loan” from the pension fund for a moment. Keep that in the back of your mind.

It’s all very well to say the company was “fully obligated to repay the money back to the plan”. It was also obligated to pay back its other creditors.

You may have noticed that in bankruptcy proceedings, the bankrupt parties don’t go to jail for stealing. They may have borrowed money in the past noting that they were “fully obligated to repay the money” … but that didn’t mean the money was fully repaid.

Of course, there are many ways to “borrow funds” from pensions.

One way is to not make contributions in the first place.

October 1, 2013, Roger Lowenstein, WSJ: “The Long, Sorry Tale of Pension Promises”

Back in 1963, Studebaker, an independent auto maker in South Bend., Ind. was struggling to compete with the Big Three. Desperate to stay afloat, the company had increased the benefits it was promising to its retirees four times in the 1950s and early 1960s. What was desperate about this? Pension benefits aren't paid out of thin air; sponsors are supposed to set aside a sum of money proportional to the benefits that will eventually come due. If the money is invested prudently, the fund will have enough assets to meet its obligations.

Here's the rub: While Studebaker was nominally increasing benefits, it hadn't the slightest hope of making the requisite contributions. The "increases" were a fiction, but when you have no cash, promising future benefits is the best you can do, whereas raising salaries is out of the question. The United Auto Workers was complicit in this fiction. Union officials reckoned that it was better to tell the members they had won an "increase" rather than to admit that their employer was going bust.

Studebaker halted U.S. operations at the end of '63, and the company terminated its pension plan. Workers saw the bulk of their pensions go up in smoke. The loss was devastating—$15 million—and Washington didn't offer a bailout. People were shocked, though it isn't clear why. In 1950, when General Motors agreed to a pension plan, a young consultant named Peter Drucker had termed the landmark agreement a "mirage," doubting whether any company could anticipate its finances and the actuarial evolution of its workforce decades hence.

Planning wasn't the problem. Auto makers knew their pensions were underfunded—they simply preferred to spend their cash on sexy tail fins or executive bonuses. The Studebaker failure moved Congress to enact a remedy, although it took its sweet time, finally getting around to approving the Employee Retirement Income Security Act in 1974.

Pay attention to the intentional underfunding of pensions. Studebaker wasn’t the only case, with respect to private pensions.

And not even since ERISA came into law.

PBGC and Terminated Plans: Both Bankrupt and Fully-Funded

There are two types of private pension plans covered by the PBGC: single-employer and multiemployer plans (often union plans).

I’ve written about multiemployer plans before, and there was a huge bailout of MEPs during the pandemic (and the reason for this had nothing to do with the pandemic. Politicians and interested parties were being opportunistic.)

The politics of private single-employer plans and MEPs have differed….

….and the politics of public pensions, not covered by the PBGC at all, are another issue as well.

But let me grab the PBGC’s own data book(s), and make a few graphs with what they give. I will stop the data at 2019 (because I want to combine in 5-year intervals).

Single-Employer Plan Terminations

There are two types of plan terminations noted, and it’s important to note the difference:

Standard terminations, where a pension plan is terminated, but it’s not bankrupt — full pension benefits will be paid to the beneficiaries, but no further benefits accrued, etc.

Trusteed terminations, where the plan is bankrupt, and the PBGC will be taking the plan over for the beneficiaries. Participants may or may not be getting full benefits, depending.

The standard terminations, as you can see, were few in number soon after ERISA, but grew in the 1980s, and peaked in the late 1980s — the age of THAT GUY:

Yeah, traditional DB (defined benefit) pension plans went by the wayside in the 1980s. Hold what you’re thinking for a moment, because I will come back to that.

Let’s look at those trusteed terminations, which were the bankrupt plans:

Unlike the standard terminations, which were by choice (and involved making sure the pensions were 100% funded), these were the failed plans. There is no particular pattern here by count.

For the single-employer plans, it will not surprise you much that most of these plans are smaller, with not that many covered employees. However, there were some large plans and claims:

This is to give you a flavor.

Defined Benefit plans in abeyance; growth of Defined Contribution

A different data book from the Department of Labor:

The above is the count of plans, and not of covered employees. Note that there was an increase in DB plans during the 1980s before they also shut them down.

It’s been pretty stable since. Those who have opted for DB plans have mainly stuck to them — but note: this does not include public pension plans (not that one expects the number of those to change).

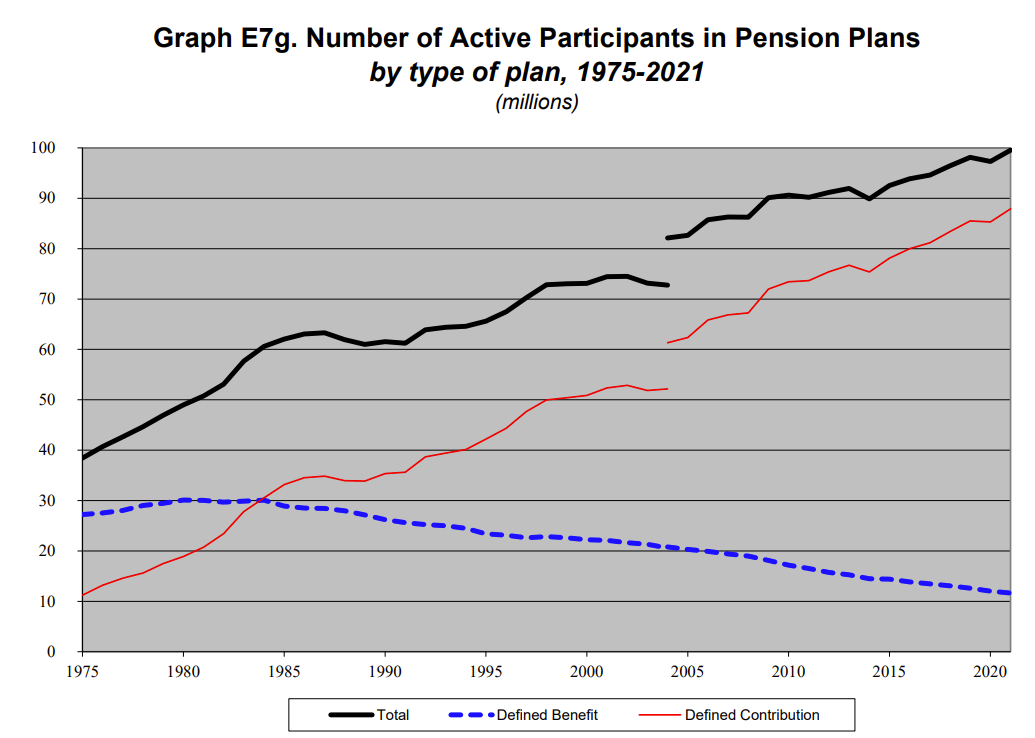

So here is the item to watch: the number of people participating.

While the number of plans is a count from filings with the IRS (because the private plans have to file to get the tax break for having retirement plans), the number of people participating has to be estimated. Due to a change in their method of estimation, there is a discontinuity in the mid-2000s.

Last graph on participation:

Active participants are those who are working and accruing credits in the plan.

DB pensions are a very pricey promise (lifetime income based on final average salary - that’s the traditional benefit formula), and ERISA finally made those promising to recognize that cost. When made to fund these promises and to carry it on the balance sheet, many companies just decided it was simpler and cheaper to go the DC (defined contribution) direction.

For many years, the ways sponsors were able to dodge the full cost was because nobody made them recognize it. Other dodgy practices occurred as well (such as company’s own stock in the pension plan). Company’s own stock is also a bad idea in the 401(k), just from a risk management point of view.

ERISA protects those in DC plans and other employee benefits. It has had a lot of salutary effects. It has provided incentives for employers to provide any type of retirement benefit, and to make sure they’re not being dodgy in a variety of ways. This is true for both DB and DC plans.

ERISA also covers non-retirement employee benefits, but I’m not getting into that.

Let me shift shortly to the multiemployer plans.

Multiemployer Extravaganza!

There is no way I’m going to link all my MEP posts. I’ve got a lot.

The main deal is: the PBGC guarantee for MEPs when they go bankrupt is very low.

And even with that very low guarantee, the Central States Teamsters pension plan was going to wipe out the MEP program — next year, essentially. All sorts of things were put forward, but there was no meeting of minds, and the disaster kept being projected to 2025.

2016: Central States: I Guess the Plan is To Run Out of Money

However, if the PBGC runs out of money by 2025 as projected, Central States participants would not receive even this greatly reduced benefit and would have their benefits reduced to nearly zero.

Dec 2020: On the Bailouts That Didn't Happen, Part 1: Multiemployer Pensions

MEPs: the disaster that the federal government has to address soon

There are two reasons that multiemployer pensions have to be addressed:

1. The federal government partially created the problem

2. Central States Teamsters plan, which has hundreds of thousands of participants, is going to fail in a few years and take down all MEP backing in the PBGC

But luckily, COVID came along, which gave politicians the perfect excuse to throw a bunch of money at MEPs, saving Central States and the PBGC:

MoneyPalooza Monstrosity: It Passed! More on the Multiemployer Pension Bailout

Well, they did it. They finally did it.

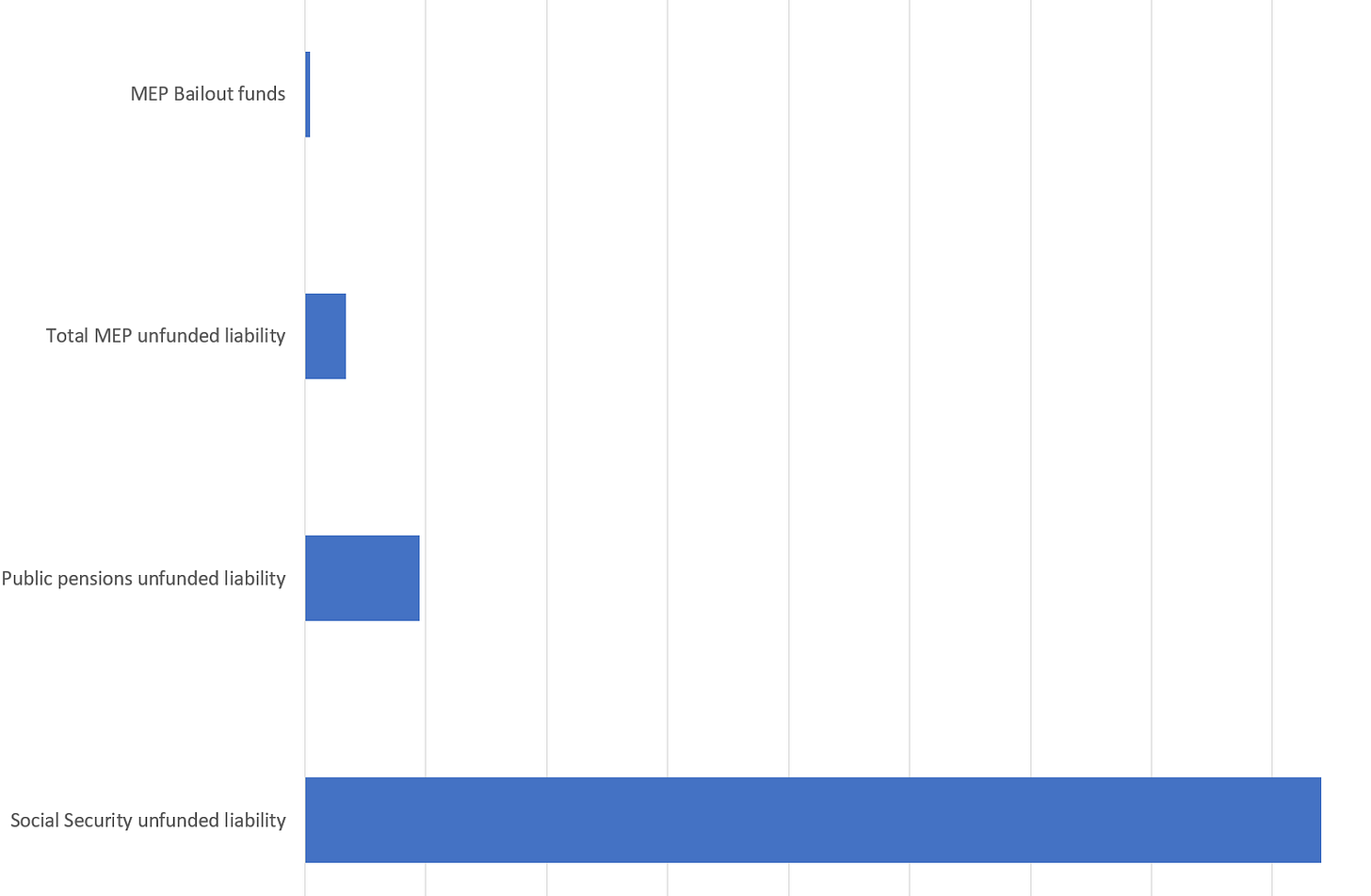

Let’s make a comparison of the MEP bailout (or the cost they put on it — for all I know, more money will be thrown at the issue), and few salient other items:

Oh wait, what isn’t covered by ERISA?

Public pensions.

(also “church plans” which also controversial…. but I will drop that for now)

Where PBGC is there to step in to provide a backstop for those in failed private pensions, when public pensions fail, the expectation is that taxpayers will make the pensioners whole.

It does help to have taxpayers around to do that.

I remember that graph comparing the MEP bailouts to the other future needs. That plus the fact that Chicago and Illinois couldn't get even a hint of future federal help with a young Chicagoan as President gave me some hope that we wouldn't try to fix these problems with a flood of money. The MEP bailout is a pretty depressing precedent though.