GameStop Follies: The Long and the Short of It

Well, it looks like the GameStop follies continue:

GameStop Corp. shares skyrocketed in the final hour of trading Wednesday, finishing the day with a rally reminiscent of last month’s blockbuster gains.

Shares of the videogame retailer finished 104% higher to close at $91.71 after hovering below $50 for most of the day. The stock, which was halted twice on Wednesday for volatility, closed around that level on Feb. 3. It climbed further in after-hours trading.

Options activity tied to GameStop also hit the highest level in two weeks, with bullish contracts significantly outpacing bearish ones, Trade Alert data show.

I am not involved in trading in any of this stuff, as my main market exposure is through index ETFs and similar investment strategies. I am leveraged, in that I do have debt in my life (mortgage, credit card debt), but other than that, I don’t short any securities.

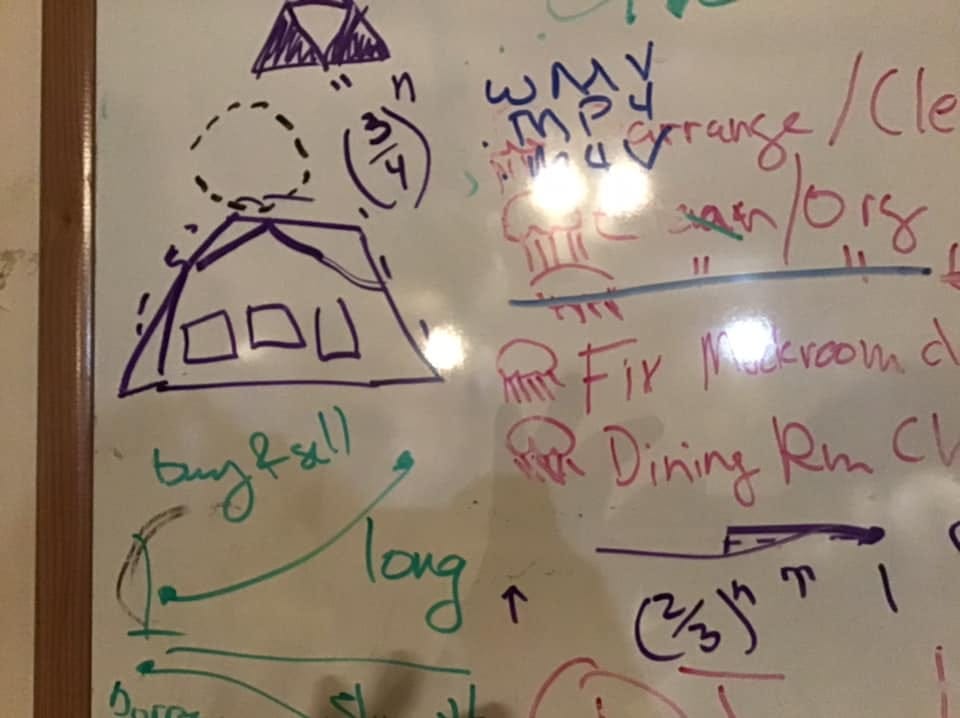

When I first wrote about GameStop at the beginning of February, I noted multiple investment/finance themes that came immediately to mind for me in a video, one of which was the first thing I explained to my kids: long vs. short positions.

(look, they came to me and asked)

If you don’t want my explanation, you can go to Investopedia: Long Position vs. Short Position: What’s the Difference?

Long positions in stocks

Let’s start with the easiest thing to explain: a long position in a stock.

You buy a stock. That’s it. That’s the long position in a stock.

Okay, okay, let’s get into it a bit more and think about how stocks work. You have a publicly-traded stock, meaning that people can buy and sell these shares at places like stock exchanges, through brokers, brokerages, etc. There are only so many shares of these stocks on the market, representing fractional ownership of the company that issued the stock.

Once you own the stock, you may get a variety of benefits, such as the right to vote in shareholder elections (voting on board of directors, and there may be other shareholder actions), and perhaps the company pays dividends on the stock, which you would get as investment income. Some people automatically reinvest the dividends back into the same stock, or perhaps they invest in other stocks.

The worst that can happen to a shareholder is that the company goes kerflooey, and you lose all the money you initially put into the stock. The great thing about this kind of corporate structure is that if the firm goes bankrupt, the creditors of the bankrupt firm cannot go after the owners’ personal wealth to get paid back for what the firm had owed them. Lenders beware (and they do).

So here is your equation: you pay X to buy the stock. Let’s pretend there are no dividends, and later you sell the stock for Y. Your gain/loss equation is Y – X.

Your potential downside is -X — that is, losing all your initial investment. The value of the stock can hit zero, but doesn’t go negative. So 0 – X gets you the -X maximum downside.

What about the upside? Well, there is no theoretical limit to the price you could sell the stock at. Y can go to the moon, baybee!

So maximum downside: -X

Maximum upside: infinite

(KFC, wallstreetbets guys?! Come on, where’s the love for Popeye’s?)

Hey, Popeyes! I love your #7 spicy! Mardi Gras mustard! With seltzer and cajun fries!

Short position in a stock

Now, let’s go to the other side: shorting a stock.

Instead of buying a stock and then selling it later (taking a long position, and then closing it out), shorting is the opposite: selling a stock and then buying it back.

Now, it’s a bit more than that. Initially, you don’t own the stock. Then you borrow the stock at price X, promising to give the stock back at a future date (there are transaction costs, and issues re: dividends, voting rights, etc., but I am going to ignore all those right now). At that initial time, you sell that stock at price X. Later, you buy back the stock at price Y and return the stock to the original owner.

Your profit here (ignoring all the other costs) is X – Y: you get the proceeds from the initial sale X and then have to pay Y at a future date.

Note: the values of X & Y in my example are the same as the long position, and now we start seeing issues. Someone shorting a stock is betting that Y will be less than X — that is, they’re betting the price of the stock will go down. The most it can go down is all the way to zero, so the maximum upside is X.

What about the downside? Well, as I said before, Y can theoretically go infinitely high…. so X – Y can go infinitely negative.

Here are your limits on the short position:

Maximum downside: negative infinity

Maximum upside: X

Needless to say, there is a lot of danger in shorting stocks.

Shorting is risky

John Maynard Keynes learned this the hard way: Keynes The Speculator

John Maynard Keynes began his career as a speculator in August 1919, at the relatively advanced age of 36 years.

Keynes traded on high leverage – his broker granted him a margin account to trade positions of £40,000 with just £4,000 equity.

He traded currencies including the U.S. dollar, the French franc, the Italian lira, the Indian rupee, the German mark and the Dutch florin.

His work as an economist led him to be bullish on the U.S. dollar and bearish on European currencies and he traded accordingly, usually going long on the dollar and short selling European currencies.

These aren’t stocks, but the dynamics are essentially the same: by short-selling European currencies, if they went up in value relative to the dollar, Keynes would lose money. And given he was trading on margin (not explaining in this post – that will be later), his losses would get amplified.

Keynes soon learned that short-term currency trading on high margin, using only his long-term economic predictions as a guide, was foolhardy. By late May [1920], despite his belief that the U.S. dollar should rise, it didn’t. And the Deutschmark, which Keynes had bet against, refused to fall. To Keynes’s dismay, the Deutschmark began a three-month rally.

Keynes was wiped out. Whereas in April [1920] he had been sitting on net profits of £14,000, by the end of May these had reversed into losses of £13,125. His brokers asked Keynes for £7,000 to keep his account open. A well-known, but anonymous, financier provided him with a loan of £5,000. Sales of Keynes’s recently published book The Economic Consequences of Peace had turned out to be healthy and a letter to his publisher asking for an advance elicited a cheque for £1,500.

Keynes was thus able to scrape together the money he needed to continue trading. He had learned a valuable but painful lesson – markets can act perversely in the short-term. Of this, he later famously commented:

“The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

And this is the motto all short-sellers have to remember as they ply their trades. The wallstreetbets crew decided to make an offensive paraphrase of the sentiment, but the sentiment is the same.

Another thing to note is that the long and short positions meet in the middle: the short position can’t exist without somebody to borrow a share from (okay, we’ll ignore the naked shorts for right now).

But the long position can exist without any short-sellers. And the long position can be held indefinitely — you never have to sell your stock. On the other hand, the short seller can’t borrow the long holder’s shares indefinitely. They have to get them back.

I don’t know if “long” and “short” positions were so-named because of not only their opposing positions, but also that you could hang onto short positions for only a very short period, relatively, while long positions are for the long-term investor. Here are people discussing the etymology on Stack Exchange, but I really don’t know.

On the advisability of short-selling

One of the things that annoys me is people injecting morality into financial transactions where both sides of a trade have the same opportunities to take positions. There are iffy things in shorting — naked shorts (now illegal), but also certain leveraged strategies. Here is a piece on whether shorting should be legal at all: Should Shorting Stocks Be Illegal?:

We’ll start by defining the proposal’s scope. One can profit from investment losses by: 1) shorting directly, 2) selling call options, 3) buying put options, 4) selling futures contracts, or 5) entering swaps. This article addresses only the first tactic, that of shorting directly, and only for individual stocks. Such a rule would not prevent investors from trading options on S&P 500 futures, selling Thailand White Rice contracts, or engaging in credit default swaps.

I received four reasons for abolishing the practice of stock shorting:

1) Profiting from company failures is immoral.

2) The practice is damaging because it artificially lowers stock prices.

3) It’s a privileged investment tactic that is not available to everyday investors.

4) Short sellers manipulate the market, by conspiring.

He addresses each of these arguments, understanding the reasoning behind some of them. One certainly can have markets where short-selling is not allowed, and I’m fairly neutral on the situation. The only thing I question is the suitability of pension funds shorting stocks. But it doesn’t bug me if other people decide to take on the risk of shorting with their own money.

One from 2018: Why Short Selling Can Make You Rich But Not Popular

Dutch traders were shorting as long ago as the 1600s, including during the tulip bubble. Napoleon labeled short sellers of government securities “treasonous.” Short selling stocks — as opposed to, say, tulips — is particularly challenging because equity markets have a long-term track record of moving up rather than down. Still, it can be done. Jesse Livermore, known as the “King of the Bears,” made a fortune shorting railroad operator Union Pacific shortly before the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The collapse of Enron Corp. in 2001 marked a notable scalp for shorts including Jim Chanos, who had been among the first to question its accounting. Starting in 2011, Muddy Waters’ Carson Block raised the profile of the new breed of activist shorts by taking aim at under-the-radar Chinese companies listed in North America, including the now bankrupt Sino-Forest Corp. The practice can be perilous: Block said he stopped shorting Chinese companies for a time because “tattooed gangsters” came looking for him. Short selling remains legal in most stock markets, unlike so-called naked short selling — shorting without having first borrowed the shares. When markets go bad, governments and regulators sometimes impose restrictions in an effort to help stem the slide. The U.S. targeted short selling during the Great Depression and joined the likes of the U.K., Germany and Japan in limiting short selling or banning it during the financial crisis that erupted in 2008. China’s regulator blamed “malicious” short selling in part for a stock market crash in 2015, placing limits on the practice as well as arresting traders.

…..

Often vilified as market outlaws, investors betting against the housing market were portrayed as the good guys in the film “The Big Short.” Shorts have some backing from researchers: One paper found that the practice discourages the manipulation of earnings reports, while another showed that shorts made more accurate predictions of the share performance of U.S.-listed Chinese firms than stock analysts did. A third concluded that activist shorts were usually “factually right.”

Let’s think about that last one, because you need to understand the meaning of “activist investors”.

While some “activist investors” are literally the same groups that are political activists, this means that these are folks who are demanding specific actions, whether by a company’s board, management, or even regulators.

Those who are activists on the long side may be someone with a hefty bunch of shares, demanding that the company sell off unprofitable arms of itself (I see this happen in insurance). These are people who think that value for the shareholders can be increased if this action were to occur. They hope the value of their investment, that of the shares they hold, would appreciate in direct reaction to this action.

Activist short-sellers are different in the types of actions they advocate. These are people who are shorting the stock, and are arguing the current market value for the shares is too high. They may claim something is stinky about the financial reporting of results, and that regulators should audit the books. They may point out that management is engaged in some value-destroying activity that shareholders were unaware of. The activist shorts aren’t trying to destroy value — they claim that the true economic value was already much lower than the stock price would indicate, and that’s because the information the market has about the company is just plain wrong.

They’re being activists not because of altruism, obviously, but that the faster the market prices adjust to what they think the true value is, the less they’re exposed to the risk of getting squeezed out of their short position before they can profit.

You only win or lose when you cash out

Let’s say there is a non-dividend-paying stock for a company, that starts out at $100. One month later, the stock’s market price is $200 after there is an announcement that the company signed on a new, big client. A month after that, the stock is back at $100 once that new client has gone bankrupt. And then at month 3, the stock has dropped to $50 after an audit shows that the company has been improperly booking revenue, and that the execs have been over-spending on fancy art for their HQ.

If you bought stock at the beginning (at $100), what is your gain or loss?

From a cash point of view, you’ve neither gained nor lost anything. Not until you cash out, at any rate.

From a balance sheet point of view, you have unrealized losses of $50 at the end of month 3, if you still are in the long position of the stock. The key term is unrealized.

Let’s say that you knew there was something up w/ the company’s financial reporting, and you know that people haven’t realized it yet. Assume you short at time 0, at $100, given your knowledge. Again, the stock price goes up and down, and at month 3, the stock is at $50.

There is no realized gain or loss yet, not until you close out your short position. At month 3, the short position has a $50 unrealized gain.

Those with the long position are never forced to sell their stocks. The only time they’re forced to realize a loss is if the company goes bankrupt and their equity is wiped out.

Those with the short position, though… well, various things can force them to have to close their short position. If the short-seller couldn’t hang on to month 3, they might have had to realize a loss at the end of the first month. For short-sellers, the path the stock price takes can force them to realize a loss even if, only they could have hung on a little longer, they could have made large gains.

That’s why Keynes noted: “The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

You can be an activist shorter – you short, and then try to publicize the financial reporting problem. You try to get the SEC to take a look at the books. You point out that the company booked the revenue for the newly-signed client, even though none of the fees had been actually earned (or received) yet. After you have taken your short position, the sooner you can get the market to agree with you, the sooner you can reap your gains and move on to your next short.

But margin requirements can force someone in a short position to have to close out their trade. Even though you were correct, if you had to close out after a month, you just lost $100.

In a future post, I will explain how margin requirements and a short squeeze can force short-sellers to take a loss.

But for now, understand how risky shorting stocks and other securities can be.

I know Melvin Capital knew, and I have no sympathy for them and whatever losses they may have taken. That’s the risk you take when you short.