While I continue to collect current reactions to Mitch McConnell’s floating of the idea of state bankruptcy processes, I want to go back to January 2011, when a similar discussion reigned.

This should give you an idea of how very long-term a problem this is. And also how slowly public finance problems evolve. Because, in my opinion, even the current market downturn is not enough to drain out the public pension funds.

Not this year, at any rate.

Before I dip into this, I want to pat myself on the back for having the prescience of starting the Muni watch thread at the Actuarial Outpost back in July 2010, from which I harvested these stories [nothing more difficult than digging up old news sometimes].

Okay, it didn’t require prescience. I had already started a public pensions thread in September 2008, and a sovereign debt watch thread in May 2010. I had noticed muni bond issues starting to invade my news, and I didn’t want to sully my pretty pension & sovereign debt threads.

Munis Had a Rough Ride from November to January 2011

Jan 14, 2011: Munis Crashing For Third Straight Day, And This Is The Worst Yet

It’s hard to look at this chart, and not have your heart skip a bit of a beat.

This is the chart Joe Weisenthal was referring to:

What you want to look at is the candlestick graph. That represents the prices a muni bond fund was trading at. It dropped quite a bit. There had also been drops in November 2010 and December 2010.

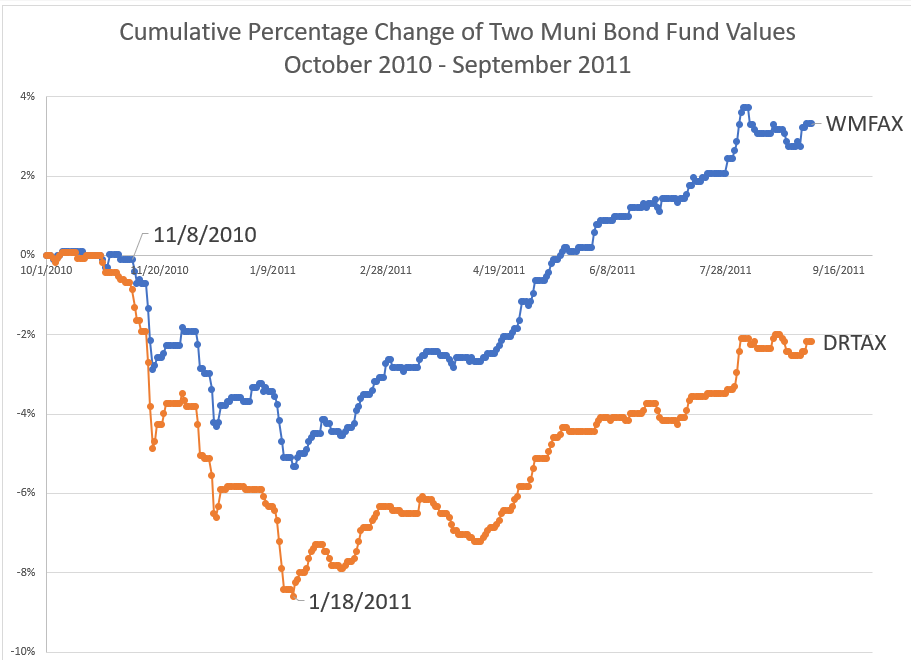

Okay, that graph is ugly, so let me provide a different one. I chose two different muni bond funds [Wells Fargo’s WMFAX & BNY Mellon DRTAX] and graphed their cumulative percentage change since October 1, 2010.

So we see a series of drops in the fund values starting at the beginning of November 2010, hit bottom around mid-January 2011, were sideways in March/April, but had made gains throughout 2011.

Key Events in Fall 2010 – Spring 2011

I want to remind people what occurred around these times which may have influenced the muni bond market.

First, the 2010 mid-term elections were held on November 2, 2010, and it was an utter rout of the Democrats. The House of Reps flipped from Democrats to Republicans, with a swing of 63 seats. After the election, the Republicans had a 242-193 majority. Not only were open seats due to retirements won by Republicans, but incumbents were defeated. Indeed, more incumbents were defeated than open seats were won by opposing parties — 54 incumbents were defeated, of which 52 were Democrats. They even lost seats in New York! [I know this, because one happened to be my district. It’s now back to the Democrats]. Many of the defeated incumbents had come in with the Democratic waves of 2006 and 2008. But some had been around since the 1990s or even the 1980s.

Now, the Democrats did not lose the Senate, which they won control of in 2006, but their majority was razor-thin after the 2010 election, with 51-47, and the balance of 2 independents who usually voted with the Democrats.

There had been a Tea Party movement that wasn’t terribly organized, but was often accompanied by the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag with “Taxed Enough Already” as the common slogan among the various groups. That partly boosted the Republican gains, but in general, it was the legislative overreach in March 2010 in passing the Affordable Care Act solely on Democratic votes that I think motivated many. In either case, this was a movement of people that would not look kindly on the bailing out of state and city pensions that many thought too generous.

On December 19, 2010, Meredith Whitney infamously predicted a wave of municipal bankruptcies in a 60 Minutes interview. She had built up credibility from an analysis she had done about Citigroup’s solvency dated October 31, 2007. Her analysis of what trouble major investment banks were in was confirmed in the October 2008 credit markets meltdown.

On January 3, 2011, the 112th Congress began.

Those are the notable events I see from this distance, which will inform on the following stories.

David Skeel Writes About State Bankruptcy Proposal

Right after the November 2010 election, David Skeel had a piece titled Give States a Way to Go Bankrupt, published in the Weekly Standard.

Here is the heart of his proposal:

When the possibility is mentioned of creating a new chapter for states in U.S. bankruptcy law (Chapter 8, perhaps, which isn’t currently taken), most people have two reactions. First, that bankruptcy might be a great solution for exploding state debt; and second, that it can’t possibly be constitutional for Congress to enact such a law. Surprisingly enough, this reaction is exactly backwards. The constitutionality of bankruptcy-for-states is beyond serious dispute. The real question is whether the benefits would be large enough to justify congressional action. The short answer is yes. Although bankruptcy would be an imperfect solution to out-of-control state deficits, it’s the best option we have, at least if we want to have any chance of avoiding massive federal bailouts of state governments.

……

But since the successful 1994 filing for bankruptcy by Orange County, California, after the county’s bets on derivatives contracts went bad, municipal bankruptcy has become increasingly common. Vallejo, California, is currently in bankruptcy, and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is mulling it over. The experience of these municipal bankruptcies shows how bankruptcy-for-states might work, what its limitations are, and why we need it now.

…..

Municipal bankruptcy differs in a few key respects from the law applying to nongovernmental entities. Unlike with corporations, a city’s creditors are not permitted to throw the city into bankruptcy. A law that allowed for involuntary bankruptcy could not be reconciled with anyone’s interpretation of state sovereign immunity. A city must therefore avail itself of bankruptcy voluntarily; no one else, no matter how irate, can trigger a bankruptcy filing. And when municipalities do file for bankruptcy, the court is strictly forbidden from meddling with the reins of government. The current law explicitly affirms state authority over a municipality that is in bankruptcy and prohibits the bankruptcy court from interfering with any of the municipality’s political or governmental powers. A court cannot force a bankrupt city to raise taxes or cut expenses, for instance. Such protections have long since quieted concerns that municipal bankruptcy intrudes on the rights of the states, and they would similarly assure the constitutionality of a bankruptcy chapter for states.

…..

The bankruptcy law should give debtor states even more power to rewrite union contracts, if the court approves. Interestingly, it is easier to renegotiate a burdensome union contract in municipal bankruptcy than in a corporate bankruptcy. Vallejo has used this power in its bankruptcy case, which was filed in 2008. It is possible that a state could even renegotiate existing pension benefits in bankruptcy, although this is much less clear and less likely than the power to renegotiate an ongoing contract.Whether states like California or Illinois would fully take advantage of such powers is of course open to question. During his recent campaign, Governor-elect Jerry Brown promised to take a hard look at California’s out-of-control pension costs. But it is difficult to imagine Brown taking a tough stance with the unions. Even in his reincarnation as a sensible politician who has left his Governor Moonbeam days behind, Brown depends heavily on labor support. He doesn’t seem likely to bring the gravy train to an end, or even to slow it down much.

But as Voltaire warned, we mustn’t make the perfect the enemy of the good. The risk that politicians won’t make as much use of their bankruptcy options as they should does not mean that bankruptcy is a bad idea. For all its limitations, it would give a resolute state a new, more effective tool for paring down the state’s debts. And many a governor might find alluring the possibility of shifting blame for a new frugality onto a bankruptcy court that “made him do it” rather than take direct responsibility for tough choices.

…….

The appeal of bankruptcy-for-states is that it would give the federal government a compelling reason to resist the bailout urge. President Obama is no doubt grateful to California for bucking the national trend in the election this month, but even he might resist bailing the state out if there were a credible, less costly, and more effective alternative. That’s what bankruptcy would offer.

You really ought to read the whole thing.

I am still skeptical about claims to constitutionality for state bankruptcy, mainly because states really are sovereigns and can default on bonds, pensions, and more. Bankruptcy as a tool requires federal court oversight, and I don’t think this really works.

But I am not any kind of lawyer, much less a constitutional lawyer.

On January 18, after the muni market turmoil, David Skeel got a WSJ op-ed:

Last week, Gov. Andrew Cuomo pledged to implement an “emergency” agenda because “the state of New York spends too much money.” Governors across the country are making similar promises, but the obstacles to achieving fiscal sustainability in many states are far too deep. To help overcome these obstacles, Congress needs to enact a law that will enable states to declare bankruptcy.

Let us stop for a moment. Cuomo is still the governor of New York. He is not the only person still in major state office who should not act like he is SHOCKED SHOCKED at the talk of state bankruptcy.

Back to his WSJ piece:

Is there anything states can do in bankruptcy that a well-motivated governor can’t do without it? You bet there is.

First, the governor and his state could immediately chop the fat out of its contracts with unionized public employees, as can be done in the case of municipal bankruptcies. In theory, the contracts could be renegotiated outside of bankruptcy, and many governors are doing their best, vowing to freeze wages and negotiate other adjustments. But the changes are usually small, for the simple reason that the unions can just say no. In bankruptcy, saying no isn’t an option. If the state were committed to cutting costs, and the unions balked, the state could ask the court to terminate the contracts.

Second, the state could reduce its bond debt, which is nearly impossible to restructure outside of bankruptcy. While some worry about the implications for bond markets, the alternative for the most highly indebted states — complete default — is far worse. Randall Kroszner, a former Federal Reserve governor now at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, showed in a 2003 study that the price of corporate bonds went up during the New Deal when the Supreme Court upheld legislation that reduced payments to bondholders. The reduction increased the prospect that bondholders would get paid. The prospect of state bankruptcy could have a similar effect, and even if it didn’t a reasonable reduction in state bond debt is essential to restructuring their finances.

Seriously? Of course they can restructure outside of bankruptcy. Sovereigns have managed to do less than a full default, without benefit of a court procedure, so pretending that’s the only choice is silly.

Third, state bankruptcy could even permit a restructuring of the Cadillac pension benefits that states have promised to public employees. These are often “vested” under state law, and in some states, like California, are protected by the state constitution. Under state law, little can be done to adjust them to more reasonable amounts.

They can amend their constitutions if they want to go that route. Of course, Rhode Island managed to change their pensions to current retirees without either bankruptcy or constitutional amendments. It depends on the state and the state constitution.

Even if voters triggered a bankruptcy filing, it wouldn’t ensure that the leaders would make the most of bankruptcy. But this too could be addressed in the fine print of the law. If Congress were willing to be especially bold, it could include provisions providing for automatic adjustments to contracts in the event the parties didn’t reach agreement within a specified period of time. Or it could automatically reduce payments as of the date of the bankruptcy filing — perhaps to 80% of amounts provided for in the contracts — until the parties reached an agreement.

That idea really undercuts the sovereignty argument.

I’m skeptical.

Some Familiar Names Were Also Negative

In response to the January 2011 piece by Skeel, there were a number of letters to the editor.

I will quote the first one in its printed entirety.

David Skeel’s one-size-fits-all bankruptcy option for states (“A Bankruptcy Law — Not Bailouts — for the States,” op-ed, Jan. 18) presupposes that all state pension funds are in the same financial sinkhole. Nothing could be further from the truth.

While many states have failed to meet their pension obligations, New York has not. The pension systems in states like Illinois (50.6% funding ratio) and New Jersey (62%) have fallen far below acceptable levels because those states have repeatedly failed to pay their required annual pension fund contributions. This year alone, New Jersey skipped a $3 billion payment. Payments delayed cost taxpayers more. That’s why the New York State and Local Retirement System has consistently been at or near a 100% funding ratio. We pay our bills.

Even for states in fiscal crisis like Illinois and New Jersey, proposing bankruptcy as a financial panacea is an irresponsible tactic with severe negative implications. Just the availability of a bankruptcy option and the potential bond default could severely damage state credit ratings and destroy the trust of bondholders. Our economy cannot withstand another crisis in confidence.

Bankruptcy may be presented as a painless way for states to walk away from bad fiscal management, but easy solutions are rarely the best solutions to very difficult problems. The best way for states to address their fiscal difficulties is to align recurring spending and revenue, not renege on obligations.

Thomas P. DiNapoli

State Comptroller

Albany, N.Y.

DiNapoli is still the State Comptroller for New York, and its sole fiduciary for state pensions.

And Illinois and New Jersey are still in trouble.

It takes a lot of time for these things to fall apart. It turns out New York did make adjustments, and has been going along. New Jersey and Illinois did not make much in the way of adjustments, and the ones they did were shot down in their respective state Supreme Courts.

If they didn’t fix their bad behavior after the financial crisis [and there was no bailout then], I can’t really see why they deserve bailouts now.

More Talk of Bankruptcy in the New York Times

Mary Williams Walsh had some pieces in the NY Times at the time.

January 24, 2011: A Path Is Sought for States To Escape Debt Burdens

Policy makers are working behind the scenes to come up with a way to let states declare bankruptcy and get out from under crushing debts, including the pensions they have promised to retired public workers.

Unlike cities, the states are barred from seeking protection in federal bankruptcy court. Any effort to change that status would have to clear high constitutional hurdles because the states are considered sovereign.

But proponents say some states are so burdened that the only feasible way out may be bankruptcy, giving Illinois, for example, the opportunity to do what General Motors did with the federal government’s aid.

Beyond their short-term budget gaps, some states have deep structural problems, like insolvent pension funds, that are diverting money from essential public services like education and health care. Some members of Congress fear that it is just a matter of time before a state seeks a bailout, say bankruptcy lawyers who have been consulted by Congressional aides.

Bankruptcy could permit a state to alter its contractual promises to retirees, which are often protected by state constitutions, and it could provide an alternative to a no-strings bailout. Along with retirees, however, investors in a state’s bonds could suffer, possibly ending up at the back of the line as unsecured creditors.

….

For now, the fear of destabilizing the municipal bond market with the words “state bankruptcy” has proponents in Congress going about their work on tiptoe. No draft bill is in circulation yet, and no member of Congress has come forward as a sponsor, although Senator John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, asked the Federal Reserve chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, about the possiblity in a hearing this month.

…..Lawmakers might decide to stop short of a full-blown bankruptcy proposal and establish instead some sort of oversight panel for distressed states, akin to the Municipal Assistance Corporation, which helped New York City during its fiscal crisis of 1975.

…….

No state is known to want to declare bankruptcy, and some question the wisdom of offering them the ability to do so now, given the jitters in the normally staid municipal bond market.

……..But institutional investors in municipal bonds, like insurance companies, are required to keep certain levels of capital. And they might retreat from additional investments. A deeply troubled state could eventually be priced out of the capital markets.

……Mr. Wilson, who ran an unsuccessful campaign for New York State comptroller last year, has said he believes that New York and some other states need some type of a financial restructuring.

He noted that G.M. was salvaged only through an administration-led effort that Congress initially resisted, with legislators voting against financial assistance to G.M. in late 2008.

“Now Congress is much more conservative,” he said. “A state shows up and wants cash, Congress says no, and it will probably be at the last minute and it’s a real problem. That’s what I’m concerned about.”

…….Unfunded pensions become unsecured debts in municipal bankruptcy and may be reduced. And the law makes it easier for a bankrupt city to tear up its labor contracts than for a bankrupt company, said James E. Spiotto, head of the bankruptcy practice at Chapman & Cutler in Chicago.

The biggest surprise may await the holders of a state’s general obligation bonds. Though widely considered the strongest credit of any government, they can be treated as unsecured credits, subject to reduction, under Chapter 9.

Mr. Spiotto said he thought bankruptcy court was not a good avenue for troubled states, and he has designed an alternative called the Public Pension Funding Authority. It would have mandatory jurisdiction over states that failed to provide sufficient funding to their workers’ pensions or that were diverting money from essential public services.

“I’ve talked to some people from Congress, and I’m going to talk to some more,” he said. “This effort to talk about Chapter 9, I’m worried about it. I don’t want the states to have to pay higher borrowing costs because of a panic that they might go bankrupt. I don’t think it’s the right thing at all. But it’s the beginning of a dialog.”

It turns out New York didn’t need restructuring. Though they did create new tiers of pensions in the state pension system.

But wait, there’s more.

Jan 27, 2011: Moody’s Credit Ratings of States To Factor In Unfunded Pensions

Moody’s Investors Service has begun to recalculate the states’ debt burdens in a way that includes unfunded pensions, something states and others have ardently resisted until now.

States do not now show their pension obligations — funded or not — on their audited financial statements. The board that issues accounting rules does not require them to. And while it has been working on possible changes to the pension accounting rules, investors have grown increasingly nervous about municipal bonds.

Okay, that all changed.

Moody’s new approach may now turn the tide in favor of more disclosure. The ratings agency said that in the future, it will add states’ unfunded pension obligations together with the value of their bonds, and consider the totals when rating their credit. The new approach will be more comparable to how the agency rates corporate debt and sovereign debt. Moody’s did not indicate whether states’ credit ratings may rise or fall.

Illinois and New Jersey are not sitting pretty with their bond ratings now, I can tell you that.

Under its new method, Moody’s found that the states with the biggest total indebtedness included Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Jersey and Rhode Island. Puerto Rico also ranked high on the scale because its pension fund for public workers is so depleted that it has virtually become a pay-as-you-go plan, meaning each year’s payments to retirees are essentially coming out of the budget each year.

Since 2011, Puerto Rico pensions did become pay-as-they-went, Rhode Island cut COLAs, and Mississippi and Massachusetts seem not to be so badly off. The others are still all screwed.

Other big states that have had trouble balancing their budgets lately, like New York and California, tended to fare better in the new rankings. That is because Moody’s counted only the unfunded portion of states’ pension obligations. New York and California have tended to put more money into their state pension funds over the years, so they have somewhat smaller shortfalls.

New York fixed their state pensions even more… and California did not. New York state plans were over 90% funded each at last measurement, some pretty close to 100% funded. Yes, I still object to their valuation approach, but they’re obviously better off than California, where its two biggest funds have been deflating in funded status for a decade.

In making the change, Moody’s sidestepped a bitter, continuing debate about whether states and cities were accurately measuring their total pension obligations in the first place. In adding together the value of the states’ bonds and their unfunded pensions, Moody’s is using the pension values reported by the states. The shortfalls reported by the states greatly understate the scale of the problem, according to a number of independent researchers.

Yes, some other things have changed since 2011, as well.

Press Release From January 2011 Turns Out To Be Correct

A spate of recent articles regarding the fiscal situation of states and localities have created the misguided impression that drastic and immediate measures are needed to avoid an imminent fiscal meltdown, according to a major new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. These articles mistakenly lump together states’ and localities’ current, largely recession-related fiscal problems with longer-term issues relating to bond indebtedness, pension obligations, and retiree health costs.

Most states are projecting large operating deficits for fiscal year 2012, as revenues remain well below pre-recession levels even as the economic downturn has increased the need for public services. States are required by law to close these deficits before the start of the fiscal year, just as they have done in each of the past three years. In contrast, states have several decades to address the above longer-term issues, whose size recent articles have tended to exaggerate.

Okay, it’s not all correct. [The size was not exaggerated]

But here’s the big point: the cash flows for the long-term liabilities — pensions, retiree healthcare, and long-term bonds — do not have the cash flows drop all at once. And, frankly, municipalities and states rarely think they’re in crisis until they have no cash at all [and when the bond market won’t give them any cash.]

The same issue holds right now, nine years later. Illinois, Kentucky, and New Jersey are still in horrible situations with respect to their pensions.

But none of these states are acting like these are real crises, because the only crisis definition they’ll recognize is when they can’t support pay-as-they-go. At which point, the results are catastrophic for retirees.

It would be nice to fix this ahead of time.

The oft-cited $3 trillion figure is based on valuing future liabilities on a so-called “riskless rate,” which looks at future costs assuming a rate of return based on conservative investments such as Treasury bonds. This is distinct from the amount that pension funds actually would have to contribute to their funds to cover their liabilities. State pension trust funds are invested a diverse mix of stocks, bonds, and other instruments and have earned a much higher return in recent decades than riskless investments. If one follows accepted state and local accounting rules and calculates pension liabilities using the historical return on plans’ assets, the unfunded liability stands at a more manageable $700 billion.

Fine, admit that public pensions aren’t riskless, and may lose out on their investments [as we are now seeing], and thus retirees get paid less than they expected.

Oh, wait, that’s not what you intended to mean?

Retiree Health Insurance

Observers claiming that states and localities are in dire crisis typically add to unfunded pension liabilities about $500 billion in unfunded promises to provide state and local retirees with continued health coverage. But these promises are of a different nature than pensions, the report explains.

While pension promises are legally binding, retiree health benefits generally are not. States and localities generally are free to change any provisions of the plans or terminate them entirely. In addition, retiree health plans differ widely from state to state, indicating that states have clear choices in the provision of retiree health benefits.

Oh wait, I totally have changed my mind. This press release is mainly bullshit.

Do you remember when Illinois tried to do some cost-sharing with its retirees? I do.

What caused this particular famous Dickensian line [“If the law supposes that, the law is a ass – a idiot”] to come to mind was an unfortunate ruling of the Illinois Supreme Court last week. The upshot of the ruling was that retiree health benefits could not be cut back, and what they meant by that was that a specific percentage of health insurance premiums would be covered by the particular pension system.

…..

Nobody is arguing that new entrants’ pensions/benefits cannot be changed. But that’s not where the trouble is coming from. It’s from an ever-ratcheting upward set of benefits for those who have been working for Illinois governmental bodies for decades and for those who are already retired.

…..

So if the state cannot cut a benefit that can fluctuate wildly from year-to-year, if the state cannot change a percentage of coverage, even if they’re paying more every year in absolute or inflation-adjusted dollars, then there’s no way the pensions, which are less variable, will be allowed to be cut.

Of course, that was into the future, so how were they to know?

Others Remember, Too

For my final link, I’m grabbing something from Bloomberg Law, from this past week:

Bid to Let States Go Bankrupt Met Rapid Demise a Decade Ago

The last time America’s states were in the throes of a crippling fiscal crisis, an idea was floated in Washington to help them swiftly bring it to an end: let them file for bankruptcy and escape from the trillions of dollars owed to bondholders and retired public employees.

It was immediately condemned by Wall Street investors, public employee unions and Republican and Democratic governors, who said it was unnecessary and would saddle them with rising interest rates by spooking the bond market. The discussion was dropped after a single hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives.

…..

But allowing states to file for bankruptcy is unlikely to gain much support, given the near universal opposition it faced a decade ago. Then, states were quick to say it was unneeded: With the broad power to raise taxes, no state has defaulted on its debt since the Great Depression. Even only a handful of struggling cities resorted to bankruptcy during the last contraction, since it was seen as a last resort that would hobble their ability to raise money for public works.

“Broad power to raise taxes”, hmmmm?

Let them try raising taxes now.

I would love to see how they think that would go. They may raise the rates… and end up with far less money.

Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics who testified before Congress during the House hearing in 2011 when state bankruptcy was last raised, said it’s just an effort to sidestep the discussion about extending aid.

Guys, Illinois actually brought up the pension issue. Seems to me they made this whole thing an issue. They never needed to mention it.

“Once you start talking about state bankruptcy being a better option than more federal assistance, you’re really saying you don’t want to provide more federal assistance,” he said.

That’s also not what McConnell said, but by all means, keep parroting that line.

There has been little speculation on Wall Street that states will be unable to pay their debts because of the coronavirus pandemic, even though it’s expected to increase the financial strains on already struggling states such as New Jersey and Illinois. While municipal bond prices tumbled last month during waves of panicked selling, they rebounded after Congress enacted the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill.

Yes, they were already struggling before coronavirus hit. After a decade of good times for the country in general. Someone might want to ask why they were struggling.

Predicting The Future is the Same as the Past

In any case, I don’t expect state bankruptcy to get anywhere this time, either.

Because those of us who aren’t interested in bailing out old debts that have nothing to do with coronavirus troubles don’t really see why they should get the bankruptcy process. And they also won’t get a bailout of their pensions.

In 2011: there was no state bankruptcy, and there was no state pension bailout.

In grand actuarial style, I will predict the past and say that’s exactly what will happen this time.