Bankruptcy Followup: On Stockton, Public Pensions, and the Prisoner's Dilemma

A chance to escape a lose-lose proposition

As mentioned before, I get emails (marypat.campbell@gmail.com) — and, unlike others, I do like getting emails correcting me on facts. I’m also fine with emails differing with me re: opinions, but facts are important because I like being right.

For me, being right isn’t about getting it right the first time — it’s about getting it correct eventually.

Why didn’t Stockton or San Bernardino cut pensions in bankruptcy?

This is going to be about correcting a statement I made in this post [and yes, once I post this, I will update that post to link here].

This was my statement:

Ultimately, Stockton pensions were not cut at all in bankruptcy, nor were San Bernardino’s. Neither city was interested in having to fight Calpers.

That was untrue, because it wasn’t really about not wanting to fight Calpers.

The reason they didn’t make pension cuts had to do with being able to retain and recruit employees.

But first, while Detroit was the first municipal bankruptcy where pensions for current retirees were actually cut, during the bankruptcy proceeding for Stockton, it was determined that they could be cut.

It’s just that Stockton [and San Bernardino after that], chose not to cut pensions.

Federal bankruptcy judge said that pensions could be cut

From October 2014: Stockton Bankruptcy Judge Rules against Pensions

A federal judge has ruled that California cities may alter pensions in bankruptcy – a move that none of the state’s three cities to enter Chapter 9 protection have attempted.

…..

Judge Christopher Klein’s ruling on Wednesday is potentially groundbreaking. Until now, CalPERS had argued successfully in the bankruptcy cases of other California cities that the amounts it requires for public worker pensions could not legally be reduced. As a potential window into his thinking, many of his questions for Stockton revolved around what it would mean for the city to exit CalPERS. At one point he noted that the so-called $1.6B exit fee to leave the pension system could be avoided in a Chapter 9 case.

So there’s that.

Stockton was concerned about an employee exodus

But from the same piece:

The city argued it was not possible to leave CalPERS and create a less expensive retirement plan. Additionally, city lawmakers have said that current and past city workers had given up enough when Stockton decided to stop subsidizing retiree and current employee’s healthcare. That cut, worth $23,000 per the average employee, amounted to anywhere from a third to a 50 percent cut in total retirement benefits for most retirees, said Councilmember Kathy Miller. “It was a moral decision and a business decision,” she told Governing during an interview last month.

Stockton’s lawyers also said Wednesday in court the city already had a “staggeringly high crime rate,” and that the average tenure of its police officers had dropped to nine years from 14 years. In court papers, the city warned that failing to pay CalPERS would cause a “mass exodus” of employees and “irreparably damage” its ability to hire new ones. But Franklin has argued the city’s plan is unbalanced because it pays some creditors back all their money, pays others much less and keeps retiree pensions intact. “The City has now wasted millions of dollars attempting to cram down an unconfirmable plan,” a pre-hearing brief said. “The time has come for the City to abandon that foolish game, end its crusade, acknowledge its obligations under the Bankruptcy Code, and propose a realistic and reasonable plan of adjustment.”

….

Still, there’s a reason three cities have avoided altering pensions thus far. Although pensions have no specific protections under the code, they ususally get favorable treatment during bankruptcy negotiations for practical reasons – they are often the biggest creditor – and for emotional ones.“In stakeholders’ minds, there’s something emotionally challenging about modifying pension claims,” said Craig A. Barbarosh, a municipal bankruptcy specialist and partner at Katten Muchin Rosenman in Costa Mesa.

Again, note, the argument from Franklin Templeton Investments is not only that the proposed settlements are unequal [hard to argue against that – they were unequal. But my understanding is that it doesn’t matter in a municipal bankruptcy, unlike corporate ones], but that the “plan of adjustment” wasn’t realistic.

It didn’t matter. It was accepted and it went through.

But let us consider the issue noted: that if they cut the current pensions [and short-changed Calpers for the unfunded liability], that people in key governmental roles [specifically fire and police] would defect to other towns. They had a point.

The prisoner’s dilemma

This is where we come to the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a classic game theory example of a coordination problem. This has been used to explain all sorts of problems, like why members of OPEC keep breaking cartel agreements.

Here is a good, short explanation in video form:

Here is a high-level explanation: there are loads of problems in real life where multiple “players in a game” end up behaving in a way that all of them are worse off, but only if they could coordinate and cooperate, they could come up with a win-win solution.

The main issue is that if only one player makes the “defecting” move, they cash in big time… but if they all do, they’re all screwed.

Coordination problems in public pensions

There can be something like this with public pensions. The moment I read ‘the city warned that failing to pay CalPERS would cause a “mass exodus” of employees and “irreparably damage” its ability to hire new ones’ from the above Governing piece, the Prisoner’s Dilemma immediately popped into my head.

This is not unique to California — and not even only at a town level. If all the other states have defined benefit pension plans for public employees, and you’re the lone state with defined contribution plans only, you may have difficulty in holding onto employees who would like to go elsewhere. However, most states have seen escalating costs, and there does come a breaking point for affordability.

There is also the issue of public employee unions, and that they can pick their candidates via active endorsement and campaign contributions [which is a coordination problem for the non-public employee taxpayers].

It is difficult to “defect” from such a coalition – while all could have less fiscal stress from at least a risk-sharing pension plan, if you are surrounded by employers offering much richer benefits, it is tough to be the first-mover. As a municipality or state, these kinds of moves are usually done under extreme fiscal duress, which is already going to make things difficult.

Crisis forces change

It is much easier to make these changes if a bunch of cities and states are making these changes at the same time. NASRA has a piece from December 2018 on significant public pension reforms, noting that

Although states have a history of making adjustments to their workforce retirement programs, changes to public pension plan design and financing have never been more numerous or significant than in the years following the Great Recession. The global stock market crash sharply reduced state and local pension fund asset values, from $3.15 trillion at the end of 2007 to $2.17 trillion in March 2009, and due to this loss, pension costs increased. These higher costs hit state and local governments right as the economic recession began to severely lower their revenues. These events played a major role in prompting changes to public pension plans and financing that were unprecedented in number, scope, and magnitude.

Part of the reason that these changes could be made is that everywhere was hit. So there wasn’t really a “better” place that public employees could go to. Public employee headcount was cut in most states, and payrolls decreased.

That said, many of the states kept the defined benefit pension plan, even if changing benefits and contribution rates for new entrants.

Others’ comments on the Prisoner’s Dilemma and public pensions

I knew I couldn’t have been the only person to have thought of this connection.

So let’s see what I find from a google search:

The Evolution of Public Pension Schemes by Harrie Verbon from 1988. This seems to be talking more about systems like Social Security, and not pension systems for public employees. However, it notes a kind of prisoner’s dilemma with regards to intergenerational transfers: in pay-as-you-go systems [like Social Security], the young are paying for the old. This holds up as long as the young think they will get transfers when they themselves are old. That may no longer hold in many countries. This paper, “POPULATION AGEING AND THE TRAGEDY OF THE PENSION COMMONS” by András Schlett in 2011 makes a similar point: ‘It delineates the “prisoner’s dilemma” situation of the approach of childbearing in today’s social insurance pension systems.’ — in this case: why suffer the costs of childbearing to fund these pay-go systems if you’ll get the old-age pension no matter what? [and then if nobody has kids….]

The next one is more promising: Public Pensions and City Solvency, edited by Susan Wachter, published in 2016. The concluding chapter, written by Wachter and Robert Inman, says the following:

On all three counts, potential allocated consequences emerge that could pose a threat in the future. -Ibe incentives to engage in under-funding reflect a prisoner’s dilemma among taxpayers: “Why should I fund my pension if I’m going to move to a new location where they haven’t funded their pension?” Such logic leads to a trend of taxpayers ignoring their own local pension liabilities in order to protect themselves. The implication is not that there will only be underfunding in one city, but rather that underfunding will be more universal.

You can go to this link to see the context, but this is about the loose practice of valuing and funding public pensions.

That coordination problem with respect to valuation could be taken away, at least, by an outside body forcing them to all value the pensions similarly. I’m not talking about the federal government doing this, by the way, but the Actuarial Standards Board, a private organization.

They could still underfund. That’s part of the 80% funded myth and “you never have to fully-fund” awful idea. But there would be a valuation standard.

By the way, I found a much earlier paper by Inman directly related to the above conclusion.

From 1982: Public employee pensions and the local labor budget

This paper examines the causes and consequences of public employee pension funding by local governments. The pension funding decision is analyzed within the context of two models: one where current taxpayers stay and pay employees’ future retirement benefits and a second model where current taxpayers move and thereby hope to avoid paying future retirement benefits. The empirical results test the alternative models for a sample of 60 large U.S. cities using data for local police and fire services. The effects of underfunding on local wages and employment is then examined and found to be significant. Implications for national pension funding policy are drawn.

Finally, that led me to this piece from 2014: 5 Answers to the Money Problem Every Big City Has. This is about pension funding, obviously. Here is the prisoner’s dilemma reference:

2. Elect Politicians Who Will Tackle the Problem

So many cities have dropped the ball on pension funding, there’s a contagion effect in play. On the expert panel, University of Pennsylvania professor Robert Inman said this has created a “prisoner’s dilemma”: Why should my city fund its pension if no one else is funding theirs? And the law has been ineffective in enforcing funding discipline, noted University of Minnesota professor Amy Monahan.

But, Monahan said, political economic forces strongly favor underfunding pensions since the time horizon of a politician is a reelection period. Politicians and taxpayers prefer to solve current crises (plowing snow after a blizzard) instead of dealing with future problems (a pension crisis in 2030).

A recent win for Democrat Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island’s governor-elect who campaigned on a record of presenting a fix to the state’s pension problems suggests that in the future, there may be some insurance for pols willing to take on pension reform.

Well, it’s been hit-and-miss so far. I’ve watched various politicians get elected with a platform of pension reform [Rauner in Illinois, Bevin in Kentucky, Christie in New Jersey, for instance] and they whiff it in various ways. Raimondo was successful in cutting COLAs, but I don’t know if that reform was sufficient.

But now we’re getting farther afield from my original point: that it can be tough to cut pensions if you’re surrounded by towns and states with much nicer benefits, and they’re hiring.

However, if external circumstances change, perhaps the problem becomes less problematic.

Perhaps California towns can now coordinate

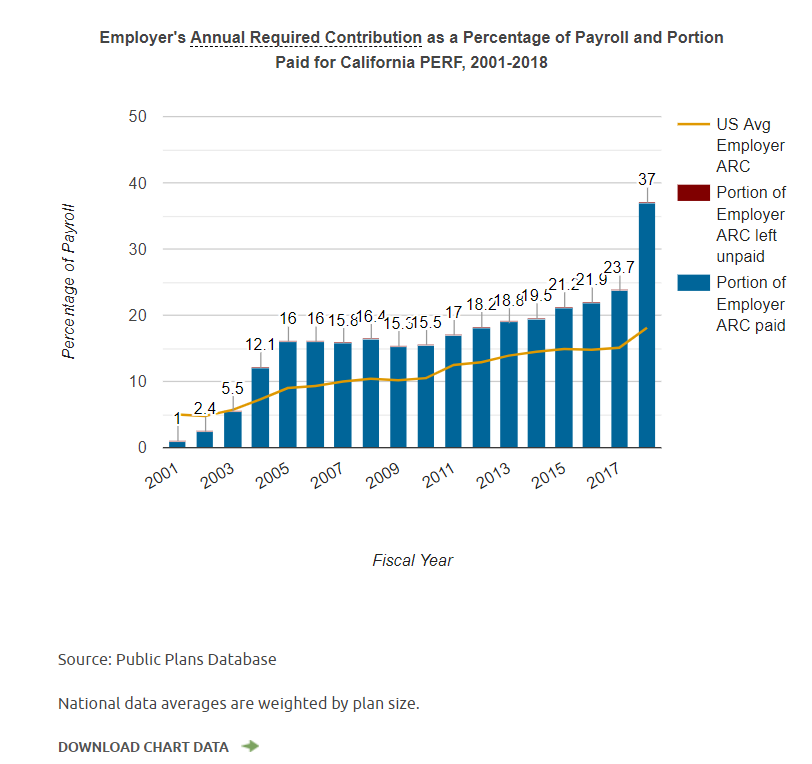

Calpers pensions are stressing out many California towns, especially since the required contributions look like this:

And that’s even before the COVID crisis.

On top of that, there’s a court case to be decided:

The California Supreme Court is expected to issue an opinion re-examining the so-called California rule for calculating public pension benefits, which has been adopted by nearly a dozen other states.

The virtual oral arguments held online Tuesday centered on whether pension benefits offered when a worker is hired become a vested right, leaving the state’s employers unable to change the way pension benefits are calculated.

At issue in the case — involving the $8.8 billion Alameda County Employees’ Retirement Association, Oakland, Calif.; the $9.3 billion Contra Costa Employees’ Retirement Association, Concord, Calif.; and $816 million Merced County (Calif.) Employees’ Retirement Association — is whether state’s 2012 pension reform law, as it applied to county pension plan participants hired before the law’s Jan. 1, 2013, effective date, was unconstitutional.

After the reform law took effect, all three pension plans applied the changes — which excluded certain pay items that had formerly been used to calculate employees’ total compensation for pension purposes — to new hires and existing employees.

….

A good portion of the argument centered on whether plan participants accepted employment based on a promise that they would receive a pension benefit based on all the types of pay that could have been included in the calculation when they were hired. Among the pay items no longer included under the 2012 state law are cash outs of vacation time and other leave pay in the final compensation calculation and payment for additional services outside of normal working hours.“One person’s pension spiking is another person’s promise,” Mr. Mastagni said. He said that reducing a pension benefits should be balanced by an offsetting advantage for the beneficiary, and employees should be able to rely on the elements that go into the calculation of their pension benefits when they are hired.

Taken to its extremes, the employees association and union arguments would prevent an employer, such as a county pension plan about to be insolvent, from making “cost-saving changes,” even if it was on the brink of bankrutpcy, California Associate Justice Joshua P. Groban commented. Is it “better to let the county go bankrupt” than to change the compensation of existing employees, he asked.

Instead of bankruptcy, the county could adjust the actuarial contributions to adequately fund the plan, Mr. Mastagni said.

I’m sorry. Give me a moment.

Okay, I really did bust out laughing when I saw that line. I’m sure there was more to the argument, and I don’t see quotes around this, but seriously.

Look again at the required contributions from Calpers. Some of these towns and counties are going bankrupt because of the actuarial contributions needed to adequately fund their plans. I am willing to bet their pension debt is their largest component of debt, when they’re so strained they feel they have to cut pensions.

I don’t want to find the court transcript myself, because there are several ways to interpret the line… and none of them, to me, is reasonable. I did find other coverage of this case, but I’m going to split that off for a separate post tomorrow.

Crisis is opportunity…but you need to be careful

I don’t have to tell you that people are doing nutty things right now.

Many people do not react well to unexpected disasters [expected disasters, like hurricanes, are more easily prepared for], so a lot of people are running under heavy cognitive loads and really can’t process large changes right now. There are too many large changes as it is.

Looking at prior crisis responses with respect to public finance and pensions, usually things don’t move too rapidly, and unlike with private business, the collapse tends to be slower. No, the 70%-ish funded level of Calpers [and I’m not gonna look at Calstrs right now] before the pandemic was not good. However, the money won’t run out immediately.

Yes, there are budget crunches right now, but the decision on pensions need not be made right away.

There is time for the cities, counties, and towns of California to coordinate and communicate once the immediate crisis is past. They can wait to see how the California Supreme Court rules. They can look at their own finances and see if they need to declare bankruptcy. They can take some time to consider their options.

But they should consider that there are options other than their current approach to pensions, and that by coordinating, they can all end up in a fiscally stronger place.

Or they can keep on what they’re doing, with ever-increasing payments while funded ratios founder.

It’s a choice.

Parting thoughts: choices have consequences

In 2014, I wrote the following:

Remember, cutting (or not cutting) pensions is a choice.

And choices have consequences.

But more to the point, that choice lasts for only so long until the money sources go away. If the choice is to cut staffing levels or to cut services to pay for underfunded pensions, people may decide to live elsewhere.

….

This is why public pensions need to be fully funded as close to the year of service as possible — later taxpayers may not feel all that beholden for service done in the 1970s. And it’s really difficult for retired people to strike. Especially if they moved to lower tax locales like Florida or Texas. If money is paid for the benefit when service is rendered, then pensioners are more secure.The concept is called “generational equity” and usually talked about in terms of “fairness”. Fairness is really beside the point, because after a while, people don’t care about “fair”. They care about trade-offs, and political realities. Those who are retired and living elsewhere are in a really weak position compared to taxpayers actually in the locale and pissed off that services are being cut. And such people may not find much solidarity from fellow public union members, when those who are still working are also hit with these taxes and also have had their benefits (and hours) cut.

So choose carefully.

It is difficult to choose carefully in a crisis, so I will change what I said.

Choose carefully… when you can think straight.